AncientPages.com – The doodles found in the margins of very old manuscripts are often just as interesting as the content of the manuscripts themselves. One such example is the frequently recurring – and extremely odd – image of knights warring against snails.

From the late 13th century through to the 15th century, images of knights fighting snails pop up in all sorts of unlikely places within the medieval literary world. And they reveal fascinating insights into what medieval people thought about the world around them.

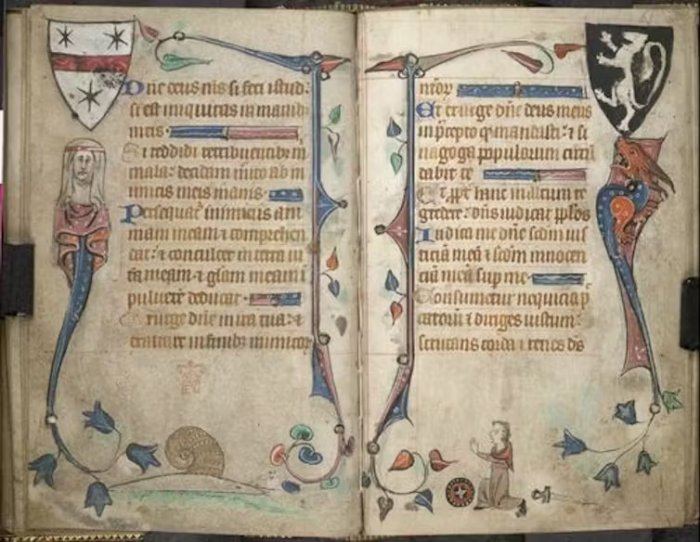

Battle in the margins from the Gorleston Psalter (1310-1324). British Library

Images of knights fighting snails first started to emerge in North French illuminated manuscripts (which are decorated with richly coloured illustrations) towards the end of the 13th century (around 1290). A few years on – although slightly less consistently – these same images started appearing in Flemish and English manuscripts.

Interestingly, in most cases these snail doodles appear to be unrelated to the adjoining illustrations of textual pᴀssages.

Often, the doodles depicted an armed knight confronting a snail whose horns were extended and pointing like arrows. In the manuscripts of the French folktale, Le Roman de Renart, the weapons that the knights were depicted with varied between sticks, maces, flails, axes, swords and even forks.

Snail ᴀssailants are almost always male knights. However, there is one known instance of a woman opposing a snail wielding a spear and shield.

As these snail combat doodles increased in popularity within manuscripts, they became an accepted element of medieval imagery. From here, they spread to other areas of medieval life.

Decorative panels carved around 1310 on the main entrance of Lyon Cathedral in France, for example, showcase a knight confronting a snail and another man threatening a dog-headed giant snail with an axe.

Despite travelling across the continent, the knights versus snails motif varied little from country to country, which suggests that it may have had a deeper meaning.

Medieval satire

Nobody knows exactly why battles between snails and knights were so popular throughout the middle ages. One theory is that these doodles added humour to texts which were otherwise quite dry and serious.

A reader could rest their eyes by taking a moment to laugh at the scene of snail combat before continuing with their reading.

Extreme jousting from Brunetto Latini’s Li Livres dou Tresor, (c. 1315-1325). Courtesy of the British Library

Many of the doodles show a knight dropping their sword or kneeling submissively before their diminutive shelled foe, which accentuates its satirical implications. There are also several representations of women pleading with knights not to attack the formidable beasts.

Other similarly lighthearted imagery includes a cat stalking a snail with the head of a mouse, as well as dogs, monkeys, dragons and even rabbits in fierce opposition with the molluscs.

The meaning of the snail motif

Snails were recognised in medieval times for their unusual strength, given that they were able to carry their home on their back. Confrontation with a snail, therefore, could represent a test of personal strength as well as mental forтιтude.

Once a symbol of deceptive courage, the snail became a creature to be hunted down and destroyed in a display of strength and bravery.

A disarmed monk faces a snail opponent, from The Book of Hours (c. 1320-1330). Courtesy of the British Library

Like many other subjects popularised in marginal illuminations of the 1300s, the snail and knight duo gradually disappeared as time wore on. They experienced a brief revival, however, in medieval manuscripts towards the end of the 15th century.

The gastropod conqueror from the Gorleston Psalter, 1310-1324. Courtesy of the British Library

A knight versus snail fight from the Smithfield Decretals ( c.1300-1340). Courtesy of the British Library

And they haven’t completely disappeared from the common imagination. Today the pairing can still be enjoyed in the nursery rhyme, Four-and-Twenty Tailors Went To Kill a Snail:

Four-and-twenty tailors went to kill a snail,

The best man amongst them durst not touch her tail;

She put out her horns like a little Kyloe cow;

Run, tailors, run, or she’ll kill you all e’en now.

Written by Madeleine S. Killacky, PhD Candidate, Medieval Literature, Bangor University

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.