Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Paleontologists have discovered the oldest known burial site in the world, containing remains of a small-brained distant relative of humans previously thought incapable of complex behavior.

The bones were buried about 30 meters (100 feet) underground in a cave system within the Cradle of Humankind near Johannesburg, South Africa. The excavation was led by renowned paleoanthropologist Lee Berger who, together with his team, announced they discovered several specimens of Homo naledi – a tree-climbing, Stone Age hominid.

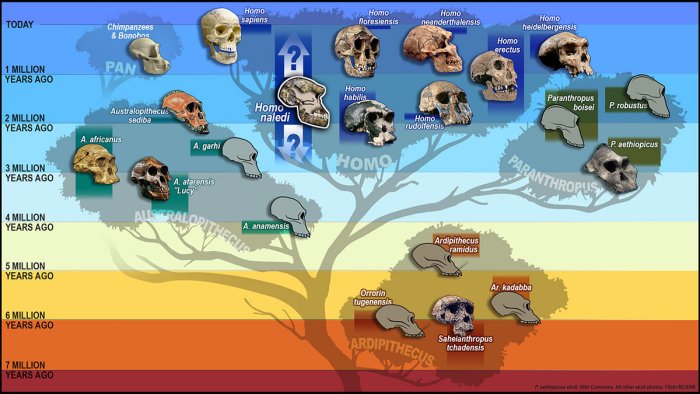

Illustration. Credit: S.V. Medaris, UW Madison

“Recent excavations in the Rising Star Cave System of South Africa have revealed burials of the extinct hominin species Homo naledi. A combination of geological and anatomical evidence shows that hominins dug holes that disrupted the subsurface stratigraphy and interred the remains of H. naledi individuals, resulting in at least two discrete features within the Dinaledi Chamber and the Hill Antechamber.

These are the most ancient interments yet recorded in the hominin record, earlier than evidence of Homo sapiens interments by at least 100,000 years. These interments along with other evidence suggest that diverse mortuary practices may have been conducted by H. naledi within the cave system. These discoveries show that mortuary practices were not limited to H. sapiens or other hominins with large brain sizes,” the scientists wrote in a series of yet-to-be peer-reviewed and preprint papers to be published in eLife.

As reported by AFP, “the findings challenge the current understanding of human evolution, as it is normally held that the development of bigger brains allowed for the performing of complex, “meaning-making” activities such as burying the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ.

The oldest burials previously unearthed, found in the Middle East and Africa, contained the remains of Homo sapiens – and were around 100,000 years old.

Skeletal remains of “Homo naledi. PH๏τo By Lee Berger research team – CC BY 4.0

Those found in South Africa by the research team led by Berger, whose previous announcements have been controversial, date back to at least 200,000 BC.

“Homo naledi tells us we’re not that special,” Berger, a United States-born explorer, told AFP news agency. “We ain’t gonna get over that.”

Homo naledi was discovered in 2013 by Berger and named after the “Rising Star” cave system, where the first bones were unearthed. Being about 1.5m (5 feet) tall, Homo naledi was primitive species described by scientists as the crossroads between apes and modern humans. It had a small brain, about the size of an orangutan, and curved fingers and toes, tool-wielding hands and feet made for walking.

“Homo naledi remains one of the most enigmatic ancient human relatives ever discovered,” Professor Lee Berger said.

“It is clearly a primitive species, existing at a time when previously we thought only modern humans were in Africa. Its very presence at that time and in this place complexifies our understanding of who did what first concerning the invention of complex stone tool cultures and even ritual practices.”

Some years ago, Professor Berger found the first partial skull of a Homo naledi child that was buried in the remote depths of the Rising Star Cave. Scientists named the child “Leti” (pronounced Let-e) after the Setswana word “letimela” meaning “the lost one”.

“This is the first partial skull of a child of Homo naledi yet recovered and this begins to give us insight into all stages of life of this remarkable species,” Professor Juliet Brophy, who led the study on Leti’s skull and denтιтion said at the time of the discovery.

The latest finding will provide scientists with valuable information about the interesting Homo naledi species.

They added that the burial site is not the only sign that Homo naledi was capable of complex emotional and cognitive behavior.

See also: More Archaeology News

As reported by AFP, “the latest research has not been peer-reviewed yet and some outside scientists think more evidence is needed to challenge what we know about how humans evolved their complex thinking.”

“There’s still a lot to uncover,” said Rick Potts, director of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program, who was not involved in the research.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer