Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – While 21st-century water companies struggle to maintain clean, fresh supplies, a new study reveals that, some 2,000 years ago, Roman water engineers were keeping up a regular program of managing and maintaining the ancient water systems.

According to the research published in Scientific Reports, ancient water management traces are captured in the limescale deposits which built up on the walls and floor of the ancient Roman aqueduct of Divona (Cahors, France).

Roman aqueduct Pont du Gard in France. Credit: Benh Lieu Song (Flickr) – CC BY-SA 3.0

The evidence shows that these deposits were regularly and partially removed during maintenance. It reveals, “The discovery of traces of regular maintenance in the carbonate deposits… such as tool marks, calcite deformation twins, debris from cleaning and repairs…are proof of periodic manual carbonate removal by Roman maintenance teams.”

The paper explains how, over decades, deposits could become many centimeters thick, clogging the aqueduct channel—if they were not cleaned out. According to the research, this was done every one to five years. It was carried out ‘rapidly and never in summer’—as recommended by Roman author Sєxtus Julius Frontinus (AD 40–103). He wrote the only known treatise about maintenance of aqueducts when he was supervisor (curator) of the waterworks of the city of Rome.

“At the start, we did not know what we were really looking for…this happens with discoveries: good and bad surprises…However, we think each aqueduct’s carbonate research from each ancient city has its own micro-story in the grander story of Roman life, waiting to be revealed,” maintained Oxford geoarchaeologist Dr. Güel Sürmelihindi.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Divona aqueduct operated between the beginning of the 1st century AD until the 4th or the early 5th century AD. Regular maintenance continued, albeit less frequently, until the last years of the aqueduct.

The paper states, “We analyzed stable oxygen isotopes to determine the seasonal (cyclic) temperature variation of water in the aqueduct, and used this profile to count the layers, recording 88 years of aqueduct activity. The position of the unconformities in this isotope profile showed that the time intervals between cleaning were one to five years, with a mean of 2.8 years, suggesting a regular cleaning regime.”

“The shape of the oxygen isotope profile showed that each cleaning was done in a short time, probably less than one month, and that this cleaning was done in spring, autumn, or winter, but never in summer.”

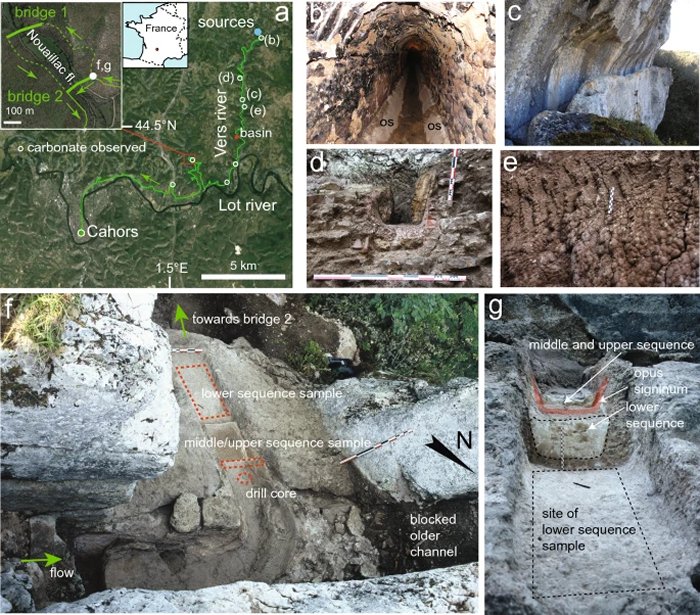

Field aspects of the Divona aqueduct. (a) Map of the aqueduct of Divona (Cahors). Carbonate samples were taken just upstream of a bridge on the Nouailhac stream (inset), whose construction shortened the aqueduct course, leaving an abandoned loop along the valley. Locations of other sites where carbonate was observed and mentioned in this article are indicated. (b) Masonry channel near the spring. Triangular wedges of ‘opus signinum’ on the lower parts of the walls give the channel an intentionally trapezoidal shape. The opus signinum is covered by a thin veneer of carbonate. (c) Rock-cut section of the aqueduct on a steep cliff. (d) Channel with sidewall carbonate where the bottom lacks incrustation. (e) Tool marks of cleaning on deposits along the sidewall in a rock-cut channel. (f) Location of the main sampling site. In the centre, carbonate deposits with the excavation stages can be seen. (g) View of the same deposits from downstream. The satellite image (a) is from Google Maps/Google Earth (data provider: Image Landsat/Copernicus) Credit: Nature

As well as throwing light on water management practiced by the Romans, the team maintains that work on the aqueduct can help to reveal something about the local economy and political stability. Perhaps, worryingly, they say, “Regular maintenance can be taken as evidence for a well-structured organization of an ancient town, while less regular maintenance…indicates socio-economic stress.”

See also: More Archaeology News

Research on the aqueducts of Divona and neighboring aqueducts is ongoing since, the authors suspect, they may give information not only on Roman life in late antiquity but also on the ultimate collapse of society in southern France due to political and environmental reasons.

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer