A mᴀssive solar outburst, known as a coronal mᴀss ejection (CME), erupted from the sun, bathing Earth, the moon, and Mars in radiation.

For the first time, instruments on all three celestial bodies registered the same event almost simultaneously. The European Space Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), NASA’s Curiosity rover, the Chinese National Space Administration’s Chang’e-4, NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), and the German Aerospace Center’s Eu:CROPIS satellite all detected the radiation.

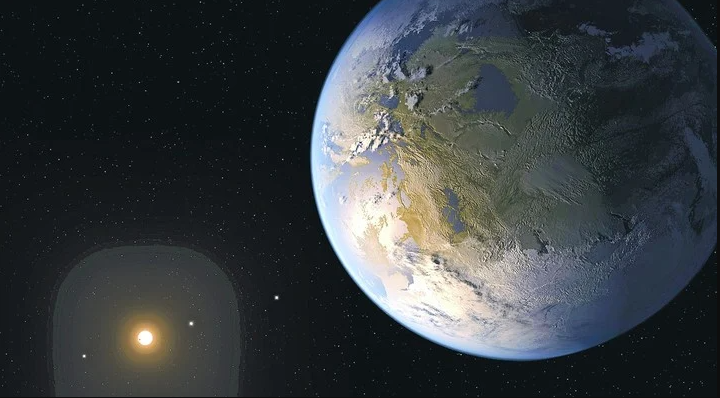

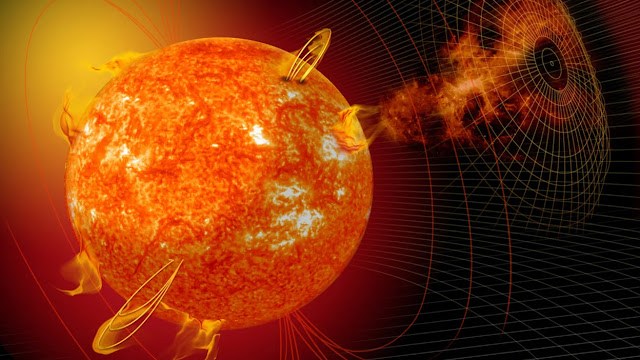

Understanding CMEs is crucial for future space exploration, including planned missions to send astronauts to Mars and to establish a scientific outpost on the moon. On Earth, our magnetic field acts as a shield against most dangerous solar outbursts. However, the moon and Mars lack this protective magnetosphere, which means that a lot more radiation makes it to their surfaces.

The CME on October 28 was much weaker than a dangerous dose, only clocking in at around 31 milligray. However, CMEs become both more frequent and more intense as the sun approaches the peak of its 11-year solar activity cycle, which could begin as soon as the end of 2023.

The study found that Earth’s magnetosphere and atmosphere rendered the radiation from the event negligible by the time it reached our planet’s surface. Mars’s surface got about one-30th of the initial dose thanks to buffering effects from its atmosphere. But just over half of the initial dose of radiation from the CME hit the moon’s surface.

While this particular CME event wasn’t strong enough to potentially sicken a human, half of the radiation from a larger outburst could be ᴅᴇᴀᴅly. Studying where and how CMEs hit bodies beyond Earth could help scientists develop the shielding necessary to protect future astronauts.

Source