Scientists have revealed that a subatomic particle called a muon has wobbled unexpectedly, suggesting that there might be a fifth force of nature besides the four known ones.

The four known forces of nature are the electromagnetic force and the strong and weak nuclear forces, which are explained by the standard model of particle physics, and gravity, which is not. The standard model also does not account for dark matter, a mysterious substance that makes up about 27% of the universe.

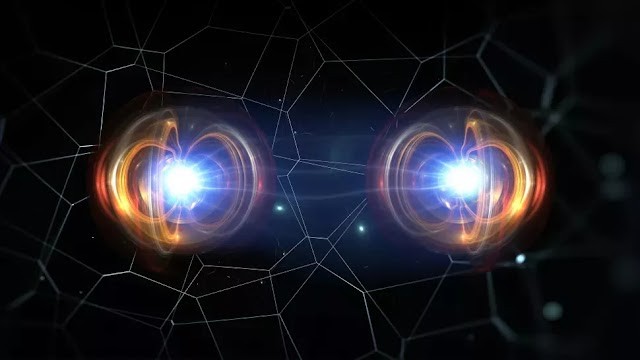

The new evidence for a possible fifth force comes from experiments at the FermiLab US particle accelerator facility, where researchers studied how muons, which are like heavy electrons, spin in a magnetic field.

The researchers expected the muons to spin at a certain frequency, based on the standard model. But they found that the muons spun faster than predicted, indicating that there might be some unknown particle or force affecting them.

Dr Mitesh Patel, from Imperial College London, said: “We’re talking about a fifth force because we can’t necessarily explain the behaviour [in these experiments] with the four we know about.”

Prof Jon ʙuттerworth of University College London, who works on the Atlas experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at Cern, said: “The faster spinning is due to how the muon interacts with a magnetic field. This interaction can be calculated very precisely in the standard model but it involves quantum loops, with known particles appearing in those loops.

“If the measurements don’t match the calculation, that could mean that there is some new particle appearing in the loops – which could, for example, be the carrier of a fifth force.”

The results from FermiLab are consistent with previous ones from the same facility. However, Patel said there was a problem: the theoretical prediction of the muon’s frequency has become more uncertain over time.

“That could change the situation. Maybe what they are seeing is standard scientific thinking – the so-called standard model,” Patel said.

There are also other challenges. ʙuттerworth said: “If the difference is confirmed, we will know there is something new and exciting but we won’t know exactly what it is.

“Ideally, the difference would inspire new theoretical ideas that would lead to new predictions – for example, of how we might find the particle that carries the new force, if that’s what it is. The final confirmation would then be building an experiment to directly discover that particle.”

The experiments at FermiLab are not the only ones to hint at a fifth force: work at the LHC has also shown some interesting findings, but with a different type of experiment looking at how often muons and electrons are produced when certain particles decay.

But Patel, who worked on the LHC experiments, said those results were now less consistent.

“They are different experiments, measuring different things, and there may or may not be a connection,” he said.

ʙuттerworth added that the discrepancy between the muon’s measured and predicted frequency was one of the oldest and most significant gaps between an observation and the standard model.

“The observation is a great achievement, and very unlikely to be wrong now,” he said. “So if the theory predictions get sorted out, this could indeed be the first confirmed evidence for a fifth force – or something else strange and beyond the standard model.”