A child’s 130,000-year-old tooth could offer clues to an extinct human relative

Palaeontologists in Laos have uncovered an ancient molar that likely belonged to a young Denisovan girl. The discovery is a big deal, as the Laotian cave in which the molar was found is now one of only three spots known to host these enigmatic humans.

In addition to Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau, we can now add Laos to the achingly shortlist of places that have yielded fossils of an elusive human species known as the Denisovans.

A team of palaeontologists found the suspected Denisovan molar at the Tam Ngu Hao 2 cave in the Annamite Mountains of Laos. The molar dates to the middle Pleistocene, and it’s the first Denisovan fossil ever to be found in southeast Asia. A paper detailing this discovery is published today in Nature Communications.

Laura Shackelford, an anthropologist from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a co-author of the new study, was excited to learn that Denisovans, like their Neanderthal cousins, inhabited a variety of environments, some of them extreme.

“Although we only have a few fossils representing the Denisovans, this new fossil from Laos demonstrates that much like modern humans, Denisovans were widespread and they were highly adaptable,” Shackelford explained in an email. “They lived in the cold arctic temperatures of Siberia, in the cold, [oxygen poor] environment of the Tibetan Plateau, and now we know they were also living in the tropics of southeast Asia.”

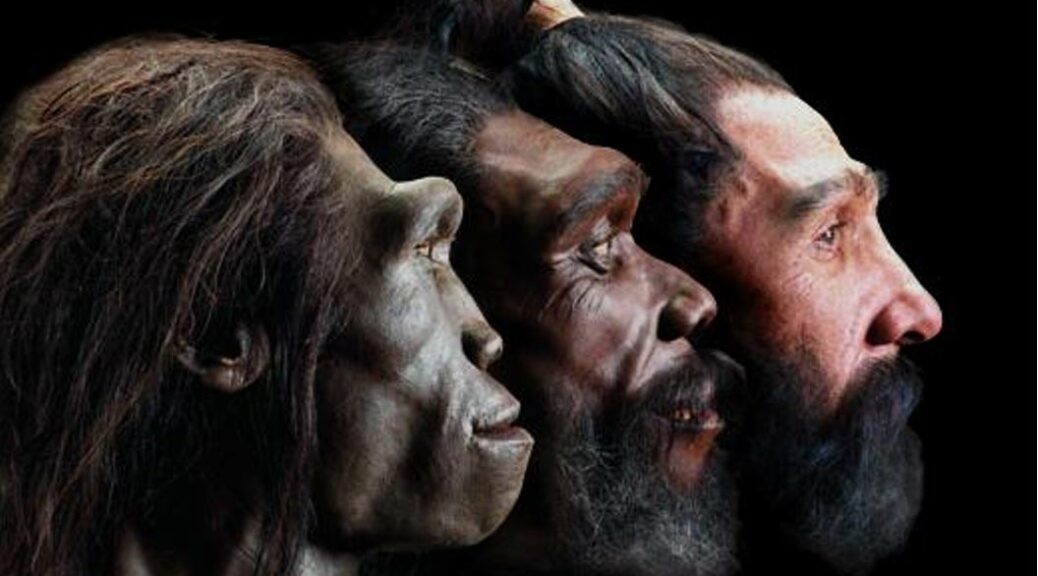

What’s more, the new discovery “further attests” that southeast Asia was “a H๏τspot of diversity for the genus Homo” during the middle to late Pleistocene, as the scientists write in their study. So in addition to Denisovans, this part of the world was once home to H. Erectus, Neanderthals, H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis, and H. sapiens.

That a Denisovan fossil was found in Laos is not a huge surprise. Traces of Denisovan DNA have been detected within the genomes of modern southeast Asian and Oceanian populations. The Ayta Magbukun—a Philippine ethnic group—have retained approximately 5% of their Denisovan ancestry, the highest of any human group in the world. Denisovans branched off from Neanderthals at some point between 200,000 and 390,000 years ago. They eventually went extinct, but not before interbreeding with modern humans. The Laotian molar is just the 10th Denisovan fossil to be found and the first outside of Siberia and Tibet.

The Annamite Mountains contain an abundance of limestone caves. Each year, Shackelford and her colleagues dispatch geologists to the area in hopes of finding spots worthy of further paleontological investigation.

“In 2018, our geologists spent the morning surveying and returned to the site before lunch with their pockets full of sediment samples that they had collected from a potential new site, what we now know as Tam Ngu Hao 2 or Cobra Cave,” Shackelford told me. “In these first samples, among fragments of fossil animal teeth, we found the tooth.”

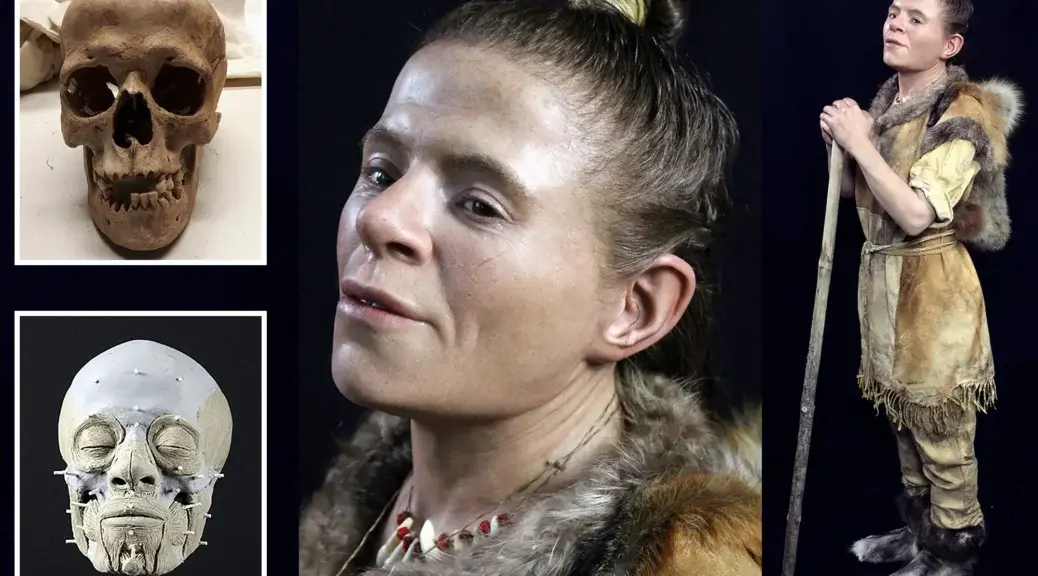

By dating the sediment in which the molar was found, the team aged the fossil to between 164,000 and 131,000 years old. Protein analysis of the tooth’s enamel identified the fossil as belonging to a member of the Homo genus, but this test couldn’t pin down the exact species.

“We do know that this is the tooth of a girl who died when she was between about 4 to 8 years old,” said Shackelford. “Since this tooth comes from a child, we are currently doing additional analyses of tooth growth and development.”

Clément Zanolli, an expert on the evolution of human teeth and a co-author of the new study, said the identification of the Denisovan molar arose from multiple lines of morphological evidence.

The Laotian molar, he told me, bears a resemblance to teeth found on the partial Denisovan mandible from Tibet, including large tooth dimensions and various distinguishing features that separate it from other Homo species known to inhabit southeast Asia, including Neanderthals and modern humans.

“Among the human groups previously cited, the molar from Laos is closest to Neanderthals, and we know from paleogenetics that Denisovans were a sister group of Neanderthals, meaning that they were closely related and shared morphological features,” Zanolli, who works at the University of Bordeaux, explained in an email. “For these reasons, the most parsimonious hypothesis is that the tooth that we found in Laos belongs to a Denisovan individual.”

It’s not impossible that the molar belonged to a Neanderthal, but if that’s the case, that “would make it the south-eastern-most Neanderthal fossil ever discovered,” according to the paper.

“We are confident it is Denisovan,” Fabrice Demeter, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Copenhagen and a co-author of the study, told me in an email. But to “further confirm our results if needed, genetic analyses would be useful,” he said. Unfortunately, however, “DNA tends to fragment more quickly and intensely in tropical environments,” and it’s for this reason that “no ancient DNA from any Pleistocene human has been sequenced so far,” he added.

The new fossil is important because it affirms something already hinted at by the genetic data—that Denisovans once inhabited a wide area of southeast Asia. What’s more, it “confirms that Denisovans were present in this region and could have met with Late Pleistocene modern humans,” according to Zanolli. And lastly, it shows that Denisovans could live in both cold, high-alтιтude environments and the tropical forests of southeast Asia.

The Denisovans appear to have been an adaptable group. But that just makes their sudden disappearance some 50,000 years ago all the more mysterious.