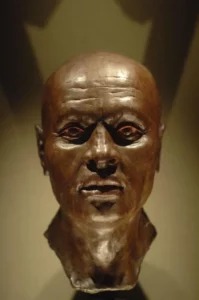

Nesyamun was a priest from the reign of Ramesses XI, around 1100 BCE. His name means “the one belonging to the God Amun.”

He worked in the temple of Karnak, which may have employed over 80,000 people at one time. Nesyamun was specifically a wab priest, which means that he reached a certain level of purification and was therefore permitted to approach the statue of Amun in the innermost sanctum of the temple. He also held the тιтles of incense bearer and scribe.

Mummification and Coffins

Nesyamun died around his 40s or 50s and was mummified with a double coffin. His body was covered in spices and wrapped in 40 layers of linen bandages. The coffins are among the best researched of their kind.

The outer coffin lid was damaged, so the above center images is what it would look like reconstructed. There are a few cracks in this coffin and its beard is missing.

Provenance

Nesyamun and his coffins were donated to the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society in 1824 by John Blaydes. This later became the Leeds Museum. Nesyamun was not the only mummy in Leeds, there were actually two other mummies and coffins in the collection.

During WWII, Leeds was bombed many times, and the museum was badly damaged. The front half of the museum was destroyed. The two other mummies were destroyed and Nesyamun’s inner coffin lid was blown out into the street. The mummy was remarkably unharmed.Eventually, the museum was moved to its new home at the Leeds City Museum in 2008.

Nesyamun’s mummy was probably unwrapped when it arrived at the museum in 1824 or shortly before. Based on pH๏τos it looks like the face and feet were the only things unwrapped or they were left unwrapped.

Katherine Baxter, Curator of Archaeology at the new Leeds City Museum (Open Setember 2008) installing their Egyptian mummy, a priest named Nesyamun, who died in his mid forties around 1100BC. Picture by Tim Smith.

Nesyamun is also bald, which is typical for a priest. He did not have many teeth left and had many splinters left in his gums, possibly from brushing his teeth with a twig. The soft palette of his mouth was also not preserved. In 1990, the Director of the Leeds Museum invited Egyptologist Dr. Rosalie David to study the mummy. She was part of a team formed in 1973 to research the living conditions, diseases, and causes of death in the ancient Egyptians. This group helped research and document Nesyamun. The Leeds Museum continued to document and research the decoration of the coffins which has led to a greater understanding of the nature of Nesyamun’s roles.

The most recent study was in January of 2020 when scientists from the University of York attempted to reconstruct the throat and trachea of Nesyamun. These used CT scans to create a 3D model of the throat. They were then able to create noise with the 3D reconstruction. It’s not the most remarkable sound and there are some concerns with the methodology which you can read here.