Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – LIDAR has once again demonstrated its advantage when locating hidden ancient sites in the jungle. Light Detection and Ranging technology is indispensable to archaeologists who can rely on laser lasers to penetrate overlying vegetation and cover swaths of ground extremely faster than they could be studied on foot.

Ecuador Amazon Rainforest. Credit. Adobe Stock – Curioso.PH๏τography

While mapping sites in the Ecuadorian Amazon, scientists detected a dense network of interconnected cities, now hidden beneath the forest in Ecuador’s Upano Valley. According to a study published in the journal Science, the settlements are at least 2,500 years old, more than 1,000 years older than any other known complex Amazonian society.

Two decades ago, archaeologist Stéphen Rostai noticed a series of earthen mounds and buried roads in Ecuador, but the discovery was not investigated further at the time.

“I wasn’t sure how it all fit together,” said Rostain, one of the researchers who reported on the finding. A recent mapping by a laser-sensor technology project has revealed that Rostain’s first discovery was part of something impressive.

Rostain and his team focused on two large settlements called Sangay and Kilamope. They found mounds organized around central plazas, pottery decorated with paint and incised lines, and large jugs holding the remains of the traditional maize beer chicha.

The results of LIDAR data offer evidence that this ancient Amazonian settlement, tucked into the forested foothills of the Andes, was once home to 10,000 farmers. It has even been suggested the settlements were home to as many as 15,000 or 30,000 at its peak, said archaeologist Antoine Dorison, a study co-author at the same French insтιтute. The number is comparable to the estimated population of Roman-era London, then Britain’s largest city.

Radiocarbon dates showed the Upano sites were occupied from around 500 B.C. and 300 to 600 A.D., a period roughly contemporaneous with the Roman Empire in Europe, the researchers found.

“It was a lost valley of cities,” said Rostain, who directs investigations at France’s National Center for Scientific Research. “It’s incredible.”

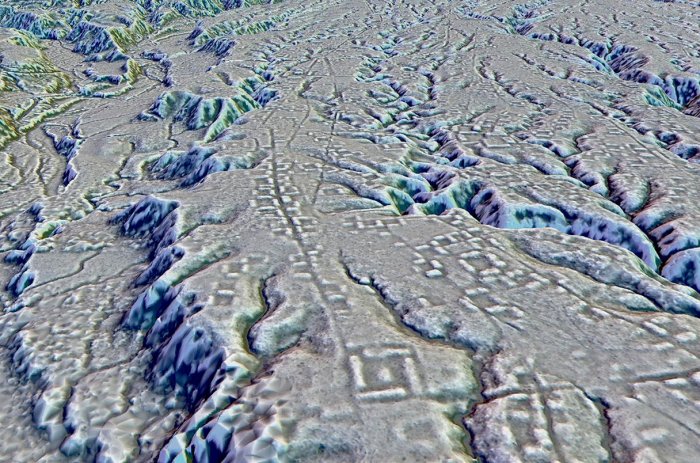

This LIDAR image provided by researchers in January 2024 shows complexes of rectangular platforms arranged around low squares and distributed along wide dug streets at the Kunguints site, Upano Valley in Ecuador. Archeologists have uncovered a cluster of lost cities in the Amazon rainforest that was home to at least 10,000 farmers around 2,000 years ago. Credit: Antoine Dorison, Stéphen Rostain

According to the study in Science, “the team identified five large settlements and 10 smaller ones across 300 square kilometers in the Upano Valley, each densely packed with residential and ceremonial structures. The cities are interspersed with rectangular agricultural fields and surrounded by hillside terraces where people planted crops, including the corn, manioc, and sweet potato found in past excavations. Wide, straight roads connected the cities to one another, and streets ran between houses and neighborhoods within each settlement. “

The largest roads were 33 feet (10 meters) wide and stretched for 6 to 12 miles (10 to 20 kilometers).

“We’re talking about urbanism,” says co-author Fernando Mejía, an archaeologist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador.

“It would have required an elaborate system of organized labor to build the roads and thousands of earthen mounds,” José Iriarte, a University of Exeter archaeologist who was not involved in the study told the ᴀssociated Press.

“The Incas and Mayans built with stone, but people in Amazonia didn’t usually have stone available to build—they built with mud. It’s still an immense amount of labor,” Iriarte added.

As explained by Rostain, there has always been an incredible diversity of people and settlements in the Amazon, not only one way to live. We keep learning more and more about these fascinating ancient sites and their inhabitants regularly.

Scientists now know people living in the Upano Valley and Llanos de Mojos were farmers who built roads, canals, and large civic or ceremonial buildings, but now researchers must also understand how these cities were functioning, including how many people lived in them, who they traded with, and how they were governed.

See also: More Archaeology News

“It’s amazing that we can still make these kinds of discoveries on our planet and find new complex cultures in the 21st century,” Thomas Garrison, an archaeologist and geographer at the University of Texas at Austin who specializes in lidar and wasn’t involved in the work said.

The study was published in the journal Science

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer