Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – A special find has been made in the Alkmaar Regional Archive: A number of 17th-century book bindings contained pieces of parchment from a manuscript from the 11th century. The original manuscript may have belonged to a princess who fled England after the Norman Conquest.

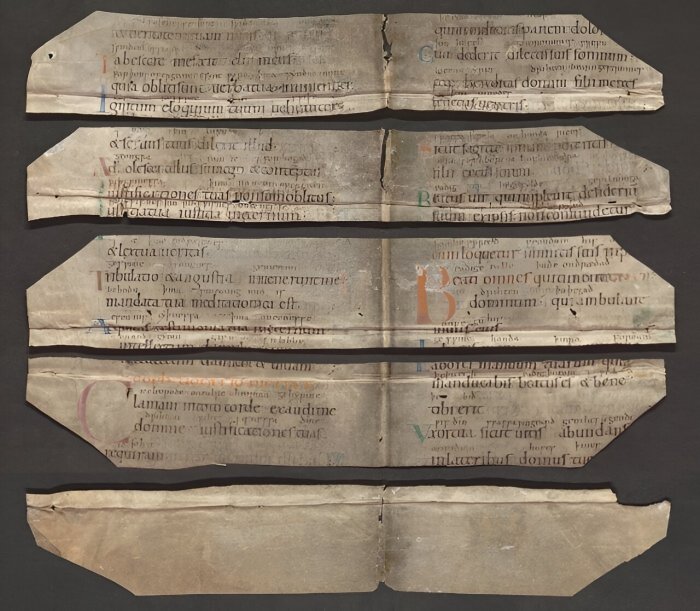

Credit: Regionaal Archief Alkmaar

Many books were printed and bound in the 16th and 17th centuries. Bookbinders used parchment to strengthen their book bindings; that material was expensive and therefore people often chose to cut up old, medieval manuscripts. This often involved manuscripts that had lost their value: books that were too Catholic or were written in a language that could no longer be read.

Something very special was found in a number of book bindings in the Alkmaar Regional Archive: 21 fragments of a manuscript from the 11th century, an almost 1,000-year-old Latin psalter with Old English glosses. Thijs Porck, senior university lecturer of medieval English in Leiden, was involved in the find and analyzed the text and provenance of the fragments.

Reading between the lines: Old English glosses in a Latin psalter

Old English was spoken between about 500 and 1100 and is very similar to German, Frisian and Dutch. This is evident from the discovered Alkmaar fragments, in which an Old English translation was written above every Latin word: “ælce dæg” above tota die; “utgang wætera” above exitus aquarum; and “halig” above sanctus. These Old English glosses probably had a didactic purpose: with this translation aid between the lines, the user of this psalter could learn Latin.

For scholars, the discovery of a total of more than 500 Old English glosses in Alkmaar is important because they teach us more about the language of early medieval England—for example, the fragments contain a number of word forms that occur nowhere else, including the word “gewændunga” for the Latin commotionem “movement”—here, you might recognize the Dutch word wending “twist, turning.”

Original owner of the manuscript: A refugee princess?

Porck’s research demonstrates that the book was bound in Leiden around the year 1600, but how did a Leiden bookbinder come to own an English manuscript from the 11th century? It is known that around the mid-16th century, manuscripts from England were shipped to the continent by boatloads, so that they could be reused by bookbinders and soap makers. It is quite possible that the manuscript with the Old English glosses was included among these, but there is also a second theory.

Credit: Adobe Stock – DanRentea

It could well be the long-lost psalter with Old English glosses that belonged to Gunhild, an English princess who fled to the continent after the Norman Conquest of 1066, taking her psalter with Old English glosses with her. Gunhild died in Bruges in the year 1087 and donated her psalter and other treasures to the St. Donaas Church. There, her psalter was last seen in the year 1561 and described as a psalter with English glosses “which one cannot properly understand here.”

Since then, every trace of Gunhild’s psalter has been lost, but Porck did manage to find out that the books of the Donaas Church were confiscated by Calvinists in the year 1580: With the useful books, they founded a public library, but other, unnecessary books were sold. A psalter with incomprehensible glosses must have belonged to the latter category—is this how the psalter ultimately ended up in the hands of a Leiden bookbinder? It just might be. Perhaps the fragments that have been found in the Alkmaar book bindings belonged to a royal book!

Porck’s article, with analysis, edition and images of the Alkmaar fragments, was published this week in the journal Anglo-Saxon England.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer