Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – The steamship Africa vanished without a trace on a stormy October night in 1895. For 128 years, many wondered what had happened to the ship, and today, we finally have an answer to this question. Yvonne Drebert and Zach Melnick, a pair of documentary filmmakers, have now solved the ship’s mysterious disappearance.

A large shipwreck was found at the bottom of Lake Huron. Credit: Inspired Planet Productions

While working on a documentary about quagga mussels in the Great Lakes, Drebert and Melnick learned a curious anomaly had been spotted by scientists on the otherwise flat bottom of Lake Huron. Was it a mound, rocks, or something else? The only way to find out was to investigate the location and surroundings.

Drebert and Melnick sailed to the specified location and sent an underwater robot to examine and send images from the depths below.

Needless to say, the filmmakers were surprised when the robotic camera captured a ship completely covered in mussels resting on the lake bed 85 meters below the surface. At the time, they had no idea they were staring at a shipwreck that had been lost for 128 years.

The water was crystal clear and images showed a large wooden ship, that “looked like a toy ship preserved in a bottle. The ship was almost perfectly intact—with one catch.

Over every part of its exterior, the distinctive yellow-brown-black shells of quagga mussels formed a solid crust, including over the stern where the boat should have borne her name. Half-sunk into the sand nearby lay a ceramic teacup, without so much as a crack,” the Canadian Geographic reports.

Eager to find out what shipwreck they had discovered, the filmmakers contacted Patrick Folkes, a marine historian and author of Shipwrecks of the Saugeen, and Scarlett Janusas, a marine archeologist.

Once the investigation team had received archaeological permission they could dive and document the submerged finding. “One way to confirm the ship’s idenтιтy would be to clear the mussels covering her name. But any effort to scrape away the mussels would rip the wood to pieces; as the mollusks settled on the downed ship, they hooked their filaments onto its surface. Cleaning the mussels would change the ship’s natural exterior, violating the Ontario Heritage Act under which it is now protected.

Drebert and Melnick returned to the wreck site a few weeks after they first spotted the ship and picked out more details. Pieces of coal sat in the silt beside the ship, remnants of her cargo. Her measurements, even under a coating of mussels, suggested a vessel of unusually long length—perhaps as long as 45 metres,” the Canadian Geographic reports.

Guagga mussels are a threat to shipwrecks in the Great Lakes forcing archeologists and amateur historians into a race against time to find as many sites as they can before the region touching eight U.S. states and the Canadian province of Ontario loses any physical trace of its centuries-long maritime history.

“What you need to understand is every shipwreck is covered with quagga mussels in the lower Great Lakes,” Wisconsin state maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen told the ᴀssociated Press. “Everything. If you drain the lakes, you’ll get a bowl of quagga mussels.”

Quagga mussels encrusting the bow of the wreck. Credit: Inspired Planet Productions

Based on the obtained underwater videos and images, scientists and filmmakers could measure the shipwreck. It was 45 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 4 meters high, and thus the same size as the steamship Africa. Pieces of coal were also found close to the shipwreck. This was another indication they had found Africa as the long-lost ship coal cargo.

On Oct. 5, 1895, Africa left Ashtabula, Ohio, for Owen Sound, with the schooner Severn in tow and carrying 1,270 tons of coal between them. On board were 10 crew, plus the captain, Hans Larsen, a 20-year veteran of the Great Lakes—the same Larsen for whom Larsen Cove, the home of Drebert and Melnick, is named.

Unfortunately, the ships were caught in a violent storm when approaching the Bruce Peninsula.

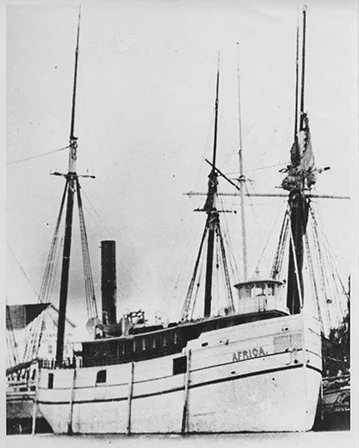

The Africa in her glory days as a pᴀssenger ship. PH๏τo credit: Historical Collections of the Great Lakes, Bowling Green State University

“Capt. Larsen either thought that we were sinking, or his vessel was foundering,” the Severn’s Captain, James Silversides, told a local newspaper days after the storm. “I think it was the latter, because he is a grand fellow, and would never have deserted us if he thought we were in a bad way.”

The Severn survived the horrible journey, but Africa disappeared and was never seen again.

“I tell you that I have pᴀssed through some bad weather during my thirty-five years’ sailing, but that experience upon Lake Huron is as bad as any. Captain Larsen was a splendid fellow to sail with, and he did all he could in this case to prevent what happened,” Captain, James Silversides said.

Folkes thinks human remains are likely still on board the Africa, perhaps in the engine room where they are beyond view.

“Without any obvious sign of human remains, the wreck cannot formally be declared a gravesite. The missing bodies of several of her crew—in death as in life—remain undocumented.

“It’s a human tragedy; those lives were lost,” says Folkes. “I always think of those poor sailors. They had pretty tough lives and ended up getting drowned in Lake Huron.”

See also: More Archaeology News

As reported by Canadian Geographic, “Drebert and Melnick plan to release their documentary, All Too Clear, next year. They ask that anyone who may have had an ancestor on board the Africa in 1895 get in touch with them through their website at alltooclearfilm.com.

They are almost 100 per cent certain that this shipwreck is the Africa. The only way to confirm is hidden under tens of thousands of mussels. What they do know is that they have located a time capsule, one that preserves a moment in 1895, but is rapidly being destroyed by the ecosystem changes of the present.”

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer