Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – In Norse mythology, God Odin always has his two raven companions, Hugin (Huginn) and Munin (Munnin), on his shoulders.

As explained earlier on Ancient pages, “Hugin represents ‘memory,’ while Munin – represents ‘thought.’

Norse God Odin with his ravens Huginn, Muninn. Credit: Adobe Stock – Karrrtinki

Hugin and Munin, “Thought” and “Memory,” fly all over Earth each morning, returning with news, gossip, and secrets to whisper in his ear. Ravens are resolutely diurnal birds; however, a raven’s cry at night signals the approach of the Wild Hunt.

Odin sends them out daily, and they fly across the world to seek important news and events. Odin surveys the worlds from Hlidskjalf and must-know reports of what is happening in all Nine Worlds.

Still, ravens were of great importance not just to God Odin but to ordinary people in general. A new study reveals ravens have shared a special relationship with humans for at least 30,000 years.

Wild animals entered into diverse relationships with humans long before the first settlements were established in the Neolithic period around 10,000 years ago.

Scientists from the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution who conducted the study have found new evidence that ravens helped themselves to people’s scraps and picked over mammoth carcᴀsses left by human hunters during the Pavlovian culture more than 30,000 years ago in what is now Moravia in the Czech Republic. The large number of raven bones found at the sites suggests that the birds in turn were a supplementary source of food and may have become important in the culture and worldview of these people.

A similar food spectrum

Ravens have a very wide food spectrum, are curious and flexible in their behavior. Their bones were discovered in large numbers at the archaeological sites of Předmostí, Pavlov I, and Dolní Věstonice I in southern Moravia. “The number of raven remains at these sites is remarkable and very unusual for the time period,” says Shumon T. Hussain. The researchers suspected that the ravens were living close to humans, perhaps attracted by their settlement activities.

The research team examined the bones of twelve common ravens from the sites and determined the birds’ diet by analyzing the nitrogen, carbon and sulfur stable isotope compositions in the bones. “These ravens fed predominantly on the meat of large herbivores, often mammoth, much like humans did at the time,” Chris Baumann explains. “We draw the conclusion that they were attracted to mammoth carcᴀsses available near human camps.”

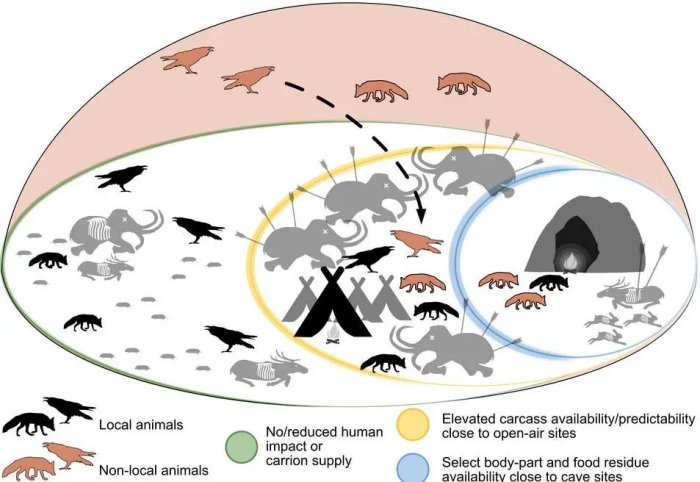

According to the team, the animals’ behavior was oriented toward what humans were doing in their environment. They say humans, in turn, took advantage of it, catching ravens, possibly for their feathers and meat. Such evidence is important for understanding early hunter-gatherer ecosystems. The researchers propose that raven behavior was synanthropic, which means that the birds benefited from a shared ecosystem with human hunter-gatherers.

The myth of pristine nature

“It is often ᴀssumed that early human foragers lived in and with a practically untouched natural environment. However, this is certainly too simple. We now know that human behavior impacted and changed ecosystems at least 30,000 years ago and that this had important effects for other organisms,” says Chris Baumann.

Relations between humans, ravens and other animals 30,000 years ago. Credit: University of Tübingen

Food scraps left by humans provided a stable food base for small scavengers, and enabled novel human-adapted feeding niches to emerge. Such niches were exploited progressively upon over time and likely became key for some species, he says. At the same time, the respective animals became more important for human cultures.

A possible side-effect of these developments was the increased likelihood of zoonoses – infectious diseases which can be transmitted between humans and animals.

The study was published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution

Written by – Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer