AncientPages.com –

[… who s]aw the Deep, […] the country,

[who] knew […], […] all […][… who] saw the Deep, […] the country,

[who] knew […], […] all […]

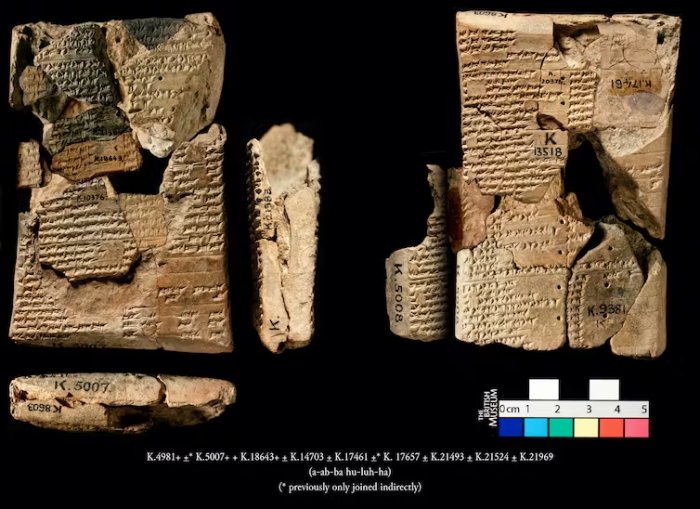

Reconstruction of the manuscript K.4981+ from nine discrete fragments previously transliterated in the Fragmentarium. Author provided

This first quote represents the beginning of the Epic of Gilgamesh as known from the 19th century onwards. The following one shows the text fully restored, in the form it achieved over 100 years later, when a new fragment of it was published in 2007.

He who saw the Deep, the foundation of the country,

who knew the proper ways, was wise in all matters!

Gilgamesh, who saw the Deep, the foundation of the country,

who knew the proper ways, was wise in all matters!

Throughout the twentieth century, only the fragmentary version of the prologue of the epic was known. Generations of readers, when first confronted with the foremost classic of ancient Mesopotamian literature, experienced the frustration of reading a fragmentary text, of being allowed only a latticed glimpse into the world of the Babylonians.

The original text was written in cuneiform, the most widespread and historically significant writing system in the ancient Middle East. Its name comes from the wedge-shaped impressions (in Latin, cuneus) that form its signs.

Regarding the impossibilty of reading the whole poem, a cuneiformist expressed in frustration: “The opening lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh, unfortunately, still cannot be completely read without making ample use of the imagination”.

This frustration is, even today, every cuneiformist’s bread and ʙuттer, often experienced “when one struggles with a fragmentary text in the Students’ Room of the British Museum and suspects with more or less reason that unidentified pieces are lying in drawers just a few meters away”. Enter the Electronic Babylonian Library Platform (eBL).

Reaching to Babylonian literature

The primary objective of the eBL project is to advance the understanding of Babylonian literature by reconstructing it to the fullest extent possible. Additionally, the project aims to provide a user-friendly platform containing extensive transliterations of cuneiform tablet fragments, along with a robust search tool, to address the abiding problem of the fragmented nature of Mesopotamian literature.

The backbone of the project is the Fragmentarium, which digitally brings together transliterations of fragments of cuneiform tablets. These cuneiform tablets were mostly excavated in the 19th century, and have been stored in the drawers of various museums since.

In particular, the British Museum holds hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets, many of which have not been read since antiquity. Our collaboration with the British Museum has digitised tens of thousands of these tablets, and transliterated them in the Fragmentarium.

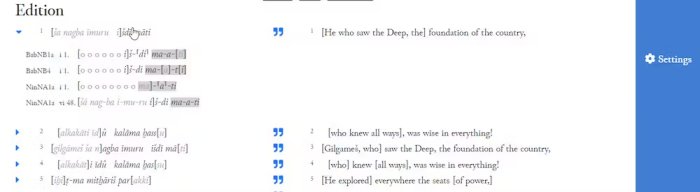

The edition of Gilgamesh I on eBL platform. George, A. R. (2022). Poem of Gilgameš Chapter Standard Babylonian I. With contributions by E. Jiménez and G. Rozzi. Translated by Andrew R. Electronic Babylonian Library, Author provided

If the Fragmentarium is the backbone of the project, its showcase is the eBL Corpus. The corpus is conceived to contain editions of all “classics” of Babylonian literature copied during the first millennium BCE, from the Epic of Creation to the Poem of the Righteous Sufferer.

The eBL editions use many previously unpublished or unedited fragments, often identified by the members of the project, and thus represent cutting-edge versions of the texts.

Relating the databases

The main problem we face is getting these two large textual databases (Fragmentarium and Corpus) to talk to each other. The literature from ancient Mesopotamia is still riddled with textual gaps, and the identification of fragments to fill these gaps has traditionally been slow and laborious due to the ambiguities of cuneiform script.

Indeed, cuneiform writing knows no orthography. There is no single, standard way of writing a word. Scribes, when copying traditional texts, would adapt them to their specific dialects or spelling preferences. Consequently, the task of fragment identification becomes challenging, as the signs present in one fragment may differ from those found in another.

As is the case in many ancient and modern writing systems, the same cuneiform character can represent multiple phonetic readings and whole words. When there is sufficient context, then multiple meaning is not a problem: usually there is only one correct reading for each sign.

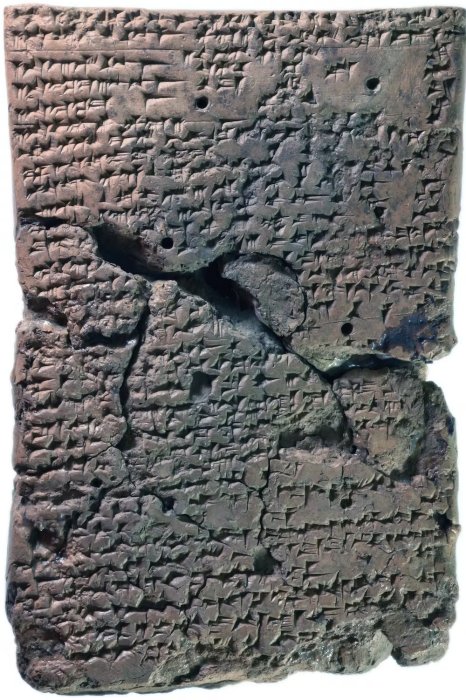

Manuscript NipNB1 (IM.77087) of Advice to a Prince (PH๏τograph by Anmar A. Fadhil, by permission of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage and The Oriental Insтιтute of the University of Chicago). Electronic Babylonian Library, Author provided

In a recent project, we trained an AI model with a relatively small corpus (less than 20,000 lines) and without using a sign list, to make this multiple meaning clear… The computer achieved a success rate of 98%.

With isolated fragments, however, there is no correct reading of a character. The reading only becomes possible if one identifies where the fragment comes from.

Also, we do not have a single complete cuneiform tablet from which to reconstruct the beginning of a work like Gilgamesh. Instead, we possess a mulтιтude of manuscripts, some of which overlap. Typically, only a few fragments of each manuscript survive.

The key to identifying additional pieces, and thus to advancing the reconstruction, lies in discovering overlaps between fragments, which will, in turn, enable the discovery of further overlaps with other fragments, and so on.

Words as our historical DNA

Interestingly, the subsтιтutions encountered in cuneiform texts bear resemblance to genetic variations found in DNA. Taking into account such variations is a central concern in bioinformatics, which has lead to the development of numerous sequence alignment algorithms.

The eBL project has implemented similar string alignment algorithm specifically tailored for cuneiform, facilitating the identification process and significantly speeding up progress.

Using this algorithm, and the various other utilities that the eBL project has made available to researchers, the team dedicated to it at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich has succeeded in identifying thousands of new fragments and significantly advanced the reconstruction of Babylonian literature.

If the 150 years of existence of ᴀssyriology prior to the project found 5,000 cuneiform pieces that could be joined to already known pieces, the five years of the eBL project have added another 1,500 to the tally, and several thousand that cannot be joined directly.

The pace is only accelerating, and it is hoped that following the publication of the electronic Babylonian Library portal in February, other researchers and amateurs will use these tools to reconstruct partly lost ancient texts.

Written by Enrique Jiménez, Chair of Ancient Near Eastern Literatures, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.