Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com – The legend of Saint Brendan’s island has not died, but this intriguing place raises many questions. Does this mythical island exist? Why does it appear on ancient maps if it was merely a phantom island?

Why have so many observed the island, yet there is no visible trace of it?

What did Saint Brendan and his followers see? Credit: Public Domain

Why haven’t modern scientists been able to locate St. Brendan’s island? Could it have been an optical illusion caused by atmospheric conditions in the area at the time? Or was the sighting of the island caused by the Fata morgana effect? Could the tiny island be submerged, or did travelers glimpse an alternate reality?

In the middle of the sixth century, St. Brendan traveled in a small boat with fourteen monks. The first written records of his voyage did not appear until 300 years later, making it difficult to determine what happened.

However, when reading the Latin text Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (“Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot“), we know that Saint Brendan and his followers landed on a small island in 512 A.D. where they held a mᴀss. The phantom island is supposedly located somewhere in the North Atlantic.

Tales of his remarkable journey captivated many during the Middle Ages, and soon many stepped forward claiming they had also seen the mysterious island.

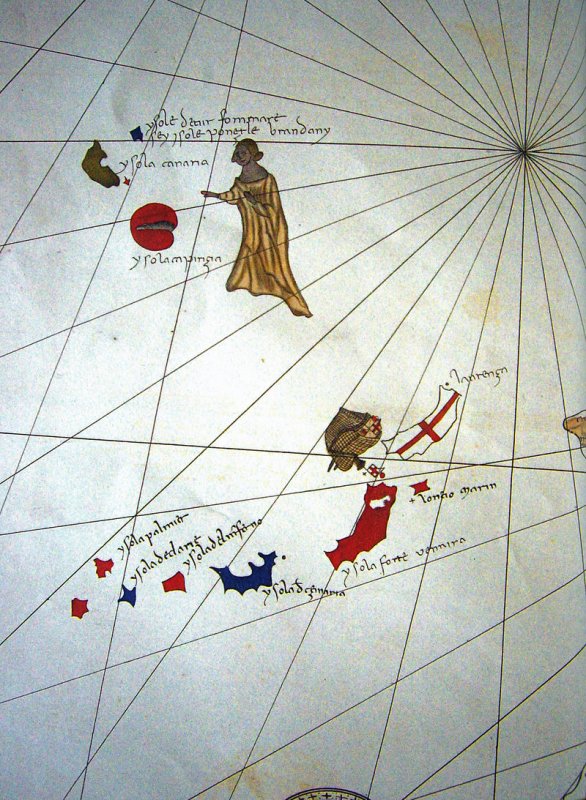

Those stories could perhaps be dismissed, but intriguingly, St. Brendan’s island appeared on many ancient maps, such as Martin Behaim’s Erdapfel of 1492. Martin Behaim (1459 –1507) was a cartographer who served Joao II of Portugal as a navigational adviser. Behaim participated in a voyage to West Africa and produced the famous Erdapfel, the world’s oldest surviving globe.

Why did Behaim add St. Brendan’s island on his map if the place never existed? Was Behaim convinced that the island was natural?

There were beautiful birds, flowers and trees on the mythical island. Credit: Public Domain

Like Eden, St. Brendan’s island was described as a beautiful place. Those who visited the island said once you set foot there, you couldn’t see any darkness because the Sun never set. According to monk Barino, who also visited the island, this was a Paradise in the Atlantic. In his writings Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis, Barino wrote this mythical and beautiful island blessed with warm weather. The island had delicious fruits, clean rivers, and beautiful birds sitting on trees.

Was the island merely a product of Barino’s imagination, gossip, and dreams about the New World?

Many ancient Portuguese writers and explorers became interested in St. Brendan’s island, and some even claimed to have spotted it before it quickly vanished again. Even Christopher Columbus is said to have believed in its existence.

In 1759 a Franciscan friar mentioned, but not identified by name, by Viera y Clavijo wrote to a friend: “I was most desirous to see the island of San Borondon and, finding myself in Alexero, La Palma, on May 3 at six of the morning, I saw and can swear to it on oath, that while having in plain view at the same time the island of El Hierro, I saw another island of the same color and appearance, and I made out through a telescope, much-wooded terrain in its central area.

Then I sent for the priest Antonio Jose Manrique, who had seen it twice previously, and upon arrival, he saw only a portion of it, for when he was watching, a cloud obscured the mountain. It was subsequently visible for another 90 minutes. We were seen by about forty spectators, but in the afternoon, when we returned to the same point, we could see nothing because of the heavy rain.”

José de Viera y Clavijo (1731 – 1813), a Spanish historian, examined the question of Saint Brendan’s Island. In his writing Noticias, Vol I, 1772, he wrote: “A few years ago while returning from the Americas, the captain of a ship of the Canary Fleet believed he saw La Palma appear and, having set his course for Tenerife based on his sighting, was astonished to find the real La Palma materialize in the distance next morning.”

Map showing St Brendan’s island. Credit: Clas Svahn: Naturfenomen, Public Domain

Viera adds that a similar entry is made in the diaries of Colonel Don Roberto de Rivas, who observed that his ship “having been close to the island of La Palma in the afternoon, and not arriving there until late the next day,” the officer was forced to conclude that “the wind and current must have been extraordinarily unfavorable during the night.”

Several expeditions were organized in the search for the island that monks, sailors, and captains frequently saw, but the sightings of Saint Brendan’s island ceased more or less from the 19th century onwards.

Many myths and legends have been confirmed by modern science, but St. Brendan’s island has never been discovered. It remains one of many legendary never, located lands that inspire countless writers around the world.

It is said that the legendary kingdom of Lyonesse disappeared underwater in a single night. Did St. Brendan Island meet the same catastrophic fate?

We can add that during the Middle Ages, writers mentioned several islands, kingdoms, and cities that had never been located. Prester John, for example, was said to be a wealthy Christian king and priest with a kingdom outside the Western European realm. With limited access to proper maps and many unexplored places, there was great confusion about where exactly his powerful kingdom was located, which has still never been found.

Many still discuss the legendary Norumberga, which remains an unsolved ancient mystery. Maybe there isn’t anything to solve because it’s possible this mythical place never existed. On the other hand, it’s curious that Norumbega suddenly vanished from early maps.

Some scholars have suggested that Norumbega could be a lost Viking settlement.

Saint Brendan’s Island may be a fictional place like the mythical places mentioned above. We cannot say why it appeared on ancient maps and what early explorers witnessed.

Updated on December 25, 2023

Written by Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com