Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – A researcher at the University of Kentucky is helping solve a mystery on the coast of North Carolina: Where did coal found on the shipwrecked Queen Anne’s Revenge come from?

About 300 years ago, a band of pirates captured a French slave ship. Among those pirates was a man named Edward Thatch (also spelled as Teach) who would be better known as Blackbeard.

Model of the Queen Anne’s Revenge in the North Carolina Museum of History. Credit: Qualiesin – CC BY-SA 4.0

The dreaded pirate captain kept the vessel, dubbing it Queen Anne’s Revenge, presumably in honor of the monarch he previously served. Blackbeard cruised the Caribbean in his new flagship amᴀssing a crew of up to 400 pirates and a hoard of treasure still yet to be discovered.

Blackbeard’s enterprise ended in 1718, after the pirates famously blockaded the port of Charleston, South Carolina. The crew left the port and sailed north where they tried to maneuver into Old Topsail Inlet in North Carolina, now known as Beaufort Inlet.

The pirate captain hit a sandbar in the inlet along the coastline. That’s where the reign of Queen Anne’s Revenge would end, and the ship would go undiscovered until 1996.

Investigating a sunken treasure

In the decades since the sunken treasure’s discovery, researchers say about half of the shipwreck has been excavated and recovered. Among the findings are gold grains, mercury, glᴀss trade beads and hundreds of pieces of coal.

A team of researchers from North Carolina and Kentucky want to know where the coal on the historic shipwreck came from. Their findings were published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology.

James Hower, Ph.D., a distinguished fellow and a research professor at the UK Center for Applied Energy Research (CAER) and Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, is part of the research team. He took a closer look at samples of coal pulled from the site.

“We wanted to figure out where this coal on the shipwreck might have come from in that particular era before there was any real coal mining of any sort in this country,” said Hower, who has more than 40 years of experience at UK researching coal and coal-combustion products.

Sourcing the coal conundrum

“There are reasons to have coal on a sailing ship like this, so finding it is not unique,” said Hower. “But in this case, we first needed to put together the entire picture of the Queen Anne’s Revenge to discern whether the coal belonged to the ship, which it most likely did not.”

Researchers cite coal was primarily used for cooking or heating in 17th- and 18th-century ships since coal wasn’t used for propulsion until the 1870s. The team found no evidence of it being used for heating or sailing on the pirate ship.

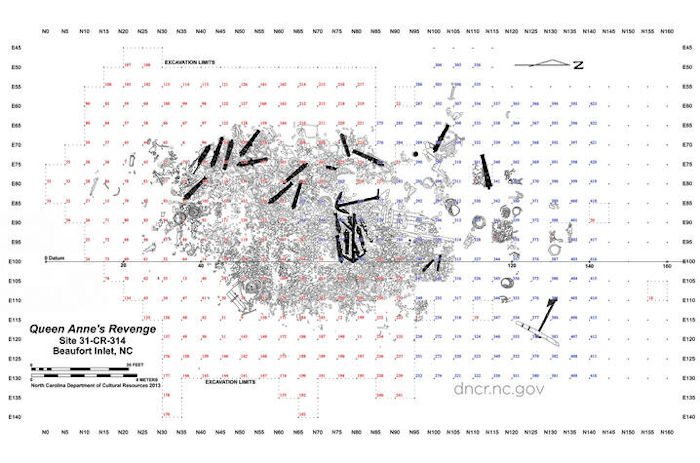

Archaeologists found coal scattered evenly across the site and expect that there could be more samples awaiting discovery in both corroded iron and unearthed areas of the wreckage.

Hower was sent four samples of the coal for further analysis at CAER’s Applied Petrology Laboratory to determine the coal rank. Coal is classified into four main ranks, or types, which depend on the amount of carbon the coal contains and the amount of heat energy it can produce.

The samples pulled from the shipwreck varied widely in rank, from low volatile bituminous coal (87-90% carbon) to anthracites (above 90% carbon). Hower explained the differences are important in understanding where the coal came from.

“Low volatile bituminous coal is generally found in Virginia. It’s good for cooking and was also used on steamships because that type of coal doesn’t give off smoke when it burns,” explained Hower. “Anthracite is not the most common coal rank found anywhere, much less in the U.S. All the anthracites here come from Pennsylvania.”

Another key to solving this mystery is knowing what time those sources of coal were active.

Researchers have mapped the underwater site where Queen Anne’s Revenge has laid for decades. Pieces of coal have been found across the site. Credit: North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

“Simply, the coal samples post-date the Queen Anne’s Revenge grounding. In a 19th- or 20th-century setting, the easiest explanation for the source of both types of coal could have been in the Appalachians, but the mining there didn’t exist in the period we’re looking at. Plus, European settlers did not discover Pennsylvania anthracite until maybe the later part of the 1760s and real, legitimate mining didn’t happen until the 1800s,” said Hower.

The coal expert listed possible sources of coal overseas in Ireland and Portugal at the height of the Queen Anne’s Revenge that could’ve been used on the ship.

Cause and coincidence?

“It turns out we didn’t need to sort out the source because the happenstance of the shipwreck and the coal was totally a coincidence,” said Hower. “It was most likely dumped from U.S. Navy ships in the Civil War era.”

The shipwreck is near Beaufort, North Carolina, an invaluable harbor and coal refueling station during the Civil War after Union troops captured nearby Fort Macon on April 26, 1862.

There was a heavy influx of ship traffic at that time, especially during the Union’s blockade of Wilmington, North Carolina—a major port for the Confederacy and the last one to fall in February of 1865.

At one point, it was ordered that 1,000 tons of coal were kept on hand in Beaufort for ships in the area. From 1862-64, 421 vessels made nearly 500 trips into the city for coal.

The station would close in 1865—147 years after the Queen Anne’s Revenge sank.

Blackbeard the Pirate. Credit: Joseph Nicholls (fl. 1726–55) – Public Domain

Researchers also cite forces of nature as a factor in why the coal settled in and around the shipwreck. The inlets and sand shoals along the Outer Banks frequently shift over the years due to waves, tidal currents, tropical storms and hurricanes.

Archaeologists said that movement is responsible for intrusive items finding their way onto the shipwreck, like 19th-century glᴀss and ceramic artifacts as well as 20th-century coins, soda bottles and even golf balls.

Hower used his expertise in coal analysis, historical knowledge of the area and logic to help form a solution to this mystery. He said the exercise in this case is an important way to help add context to this type of research.

“This research demonstrates that our studies of coal are not just for utilization. We can do something that teaches us about our history, and not just mining history,” said Hower. “One way or another, somebody used this coal. It wasn’t Blackbeard, but it was the U.S. Navy.”

The study was published in the journal International Journal of Nautical Archaeology

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer