Eddie Gonzales Jr. – AncientPages.com – How can we reconstruct Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history using only the few traces of data left in the present?

How can scientific models represent a system as complex as the Earth? Are we approaching a sixth mᴀss extinction?

Representational image – via India Today

Philosophy of science is the study of fundamental questions about what science is, how science works, and what it can tell us about the world. Bokulich specifically studies the philosophy of geosciences, dealing with fundamental questions in Earth science, ecology, climate science, and even planetary astronomy—she wrote a paper in 2014 philosophizing on Pluto’s demotion to dwarf planet, contextualizing it within the broader history of astronomy.

“If you’re trying to make new revolutionary discoveries, the perspective you get from studying the history and philosophy of science can be really helpful for scientists,” says Alisa Bokulich, a Boston University College of Arts & Sciences professor of philosophy.

Historically, geosciences haven’t received as much attention from philosophers compared to other sciences. But as changes to our planet become ever more visible, the climate crisis unfolds, and the loss of biodiversity worsens, there’s never been a more important time to interrogate the science that is attempting to steer humanity away from ecological catastrophe.

“Philosophers have the ability to look across a range of sciences, as well as the history of science, to probe the big-picture questions that scientists often don’t have the luxury to do in their everyday work,” says Bokulich, who directs the Center for Philosophy & History of Science at BU.

Two worlds reunited

Bokulich’s fascination with science and philosophy started in her teen years at an all-girls Catholic high school, Forest Ridge, outside of Seattle. During a required theology class, she asked one of the Jesuit priests to oversee an independent study in philosophy. At the same time, she found herself engrossed in physics classes and regularly discussing big questions about quantum mechanics with her teacher.

“Quantum mechanics tells us all sorts of strange things about the world, like, there can be a particle in this room that’s not in any particular place in this room. I thought, how could the world be like that?” she says. “That cultivated in me a philosophical and critically reflective atтιтude that tries to understand what the sciences are telling us about the nature of the world. And that’s what philosophy does too.”

Her physics and philosophy studies felt like two separate worlds, until she realized that they could be brought together under one umbrella in programs like the History & Philosophy of Science at Notre Dame, where she got her Ph.D. The two fields are actually so close in nature that, until the 19th century, philosophy and science were one discipline, often called “natural philosophy” or “philosophy of nature.”

“Aristotle was as much a biologist as a philosopher, and Kant was also a cosmologist—almost all of the great traditional philosophers were also doing science and reflecting on the methods of science of their day. Even the great physicists like Newton, Maxwell, and Einstein were also philosophers at heart,” Bokulich says. “Philosophy wants to understand what there is and how it works. And science is one of the most important resources for answering those questions.”

Understanding complexity

Since finding her path, Bokulich’s research has focused on the geosciences, which include fields ranging from climate science to paleontology.

“One of the things that drew me to the geosciences was wanting to contextualize climate science within the broader Earth sciences,” Bokulich says. “The more we can translate climate science to help the public understand how this science works, the more we can help society learn to trust this science and take proper action.”

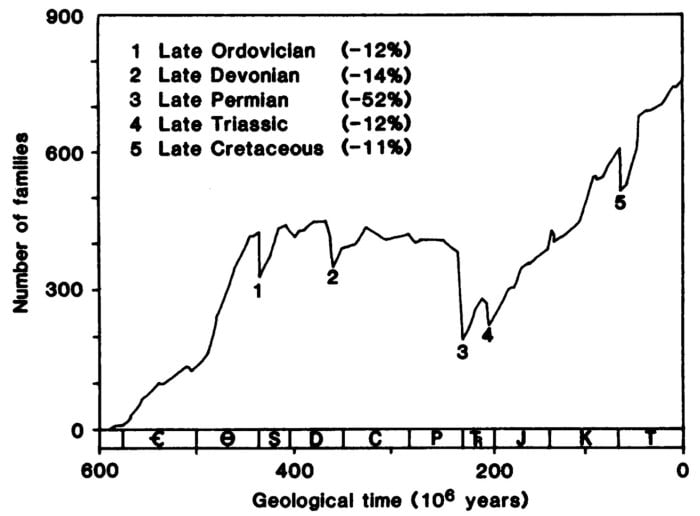

The Sepkoski Curve, representing marine diversity at the taxonomic level of families over the last 600 million years. The ‘Big Five’ mᴀss extinctions are labeled at the troughs of the diversity curve, with the relative magnitude of the drop given in parentheses in upper left (from Raup & Sepkoski [1982], p. 1502, Fig. 2; with permission from AAAS). Credit: Are We in a Sixth Mᴀss Extinction? The Challenges of Answering and Value of Asking (2023).

To give students the skills to advance those goals, she founded the Phi-Geo Group, a team of faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates dedicated to exploring research in the philosophy of geosciences—currently the only one of its kind in the world. They meet weekly, often with visiting geoscientists, biologists, and climate scientists, and hold discussions about recent papers in the field.

During the pandemic, their regular meetings (then held on Zoom) resulted in several members talking about one of the biggest open questions in geoscience: Are we in a sixth mᴀss extinction? As a result, they now have a forthcoming paper in the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, which found that, despite the rapid loss of habitat and multiple species, the numbers don’t quite add up enough to say we’re in the midst of a mᴀss extinction.

Scientists began ringing the alarm about a sixth mᴀss extinction decades ago. An author of one 2017 study that found billions of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians have been lost all over the planet said that, “the situation has become so bad it would not be ethical not to use strong language.”

The framing of entering a sixth mᴀss extinction has successfully gained the public’s attention, but is more likely to mislead than inform, Bokulich and the authors write. Their paper points out that conservationists and paleo scientists collect data differently, a major challenge when trying to compare the situation today to millions of years ago. Today’s biodiversity data is collected at the species level (think: tigers, leopards, jaguars, lions), Bokulich explains, but paleontological records are at the genus level (for those big cats, that’d be the Panthera genus).

“If we were in a sixth mᴀss extinction today, we would expect hundreds of genera to be going extinct, but we hardly know of any genera being lost in modern times, so the numbers don’t quite compare—but that doesn’t mean it’s not horrible and urgent action isn’t needed,” Bokulich says. “This is more about how awful the past mᴀss extinctions were, than a claim we don’t need to be worried about the present.”

The researchers note that to adequately address our biological and environmental crises, increased collaboration between conservation biologists and paleontologists will be needed.

“Measuring biodiversity is a complex enterprise that requires mathematical and ecological training, but also philosophical work to understand the phenomenon of biodiversity in all its complexity,” says Federica Bocchi, a fifth-year BU Ph.D. student in philosophy and lead author of the paper.

Philosophy has a white male problem

Their findings throw a wrench into the popular mᴀss extinction narrative. And it’s not lost on the authors that the paper is notable for reasons beyond the research.

“Philosophy is about 80 percent white men. To have a paper where there are five women, one who’s African American, one who’s Latina, that is very rare,” says Bokulich, who’s been a leader in a historically male-dominated field (try to name more than three philosophers you learned about in high school who aren’t men). She was the first woman to receive tenure in the philosophy department at BU in 2008 and was the first woman to become a director of a center for history and philosophy of science in North America in 2010.

“Being able to collaborate with different people from the group, along with Dr. Bokulich, has helped me further cement my values as an academic and as a woman in a very male-dominated field,” says Leticia A. Castillo Brache, a fourth-year BU Ph.D. student in philosophy and author on the extinction paper. As first-generation international students, Brache and Bocchi also say being part of the Phi-Geo Group has been one of the most valuable experiences professionally and personally while studying at BU.

To further elevate women and historically marginalized groups, Bokulich cofounded the Underrepresented Philosophy of Science Scholars initiative, which provides mentoring to hundreds of scholars and scholarship opportunities. She was recently a fellow at the Radcliffe Insтιтute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, where she conducted research for a new book project on the philosophy of the geosciences, which explores issues in the philosophy of data and modeling, and explains how scientists build reliable knowledge even in the face of great uncertainty. It will be one of the first books devoted to the philosophy of geosciences.

“There is so much exciting and urgent work to be done in this field, and we need a diversity of people exploring these questions,” Bokulich says. “We also have an opportunity to help make science and philosophy more ethical and just for everyone.”

Written by Eddie Gonzales Jr. – AncientPages.com – MessageToEagle.com Staff