AncientPages.com – The Rosetta Stone is not known for its content, but as a lexicon of Egyptian hieroglyphics. The decree inscribed on the stone, however, discusses a violent revolt—largely lost to history—that shaped the trajectory of western civilization.

Had the young pharaoh Ptolemy V been overthrown, events like the Hasmonean revolt (which established a Jewish kingdom), the affairs of Cleopatra with Julius Caesar and Marc Anthony, and even the rise of Christianity may have looked very different.

The remains of an older man who appears to have been a warrior with a healed parry fracture from his youth and an unhealed one when he died. Author provided

Until recently, the story of the struggle between the Greeks and the Egyptians was known only through Greek sources and shreds of evidence like graffiti.

Professor Robert Littman, of the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, and I uncovered evidence of the civil war at Tell Timai—the ruins of the ancient city of Thmouis in Egypt’s Nile delta. We published our research in the Journal of Field Archaeology. The archaeological evidence has revealed widespread destruction from the time of the rebellion, 204-186BC.

In 2009, evidence of burned buildings with ceramic vessels still in place first suggested that there had been a catastrophic event at Tell Timai. The destruction was widespread and followed by a leveling and rebuilding of the ruined city. Over the following years, evidence including weapons and unburied bodies that graphically pointed to an episode of extreme violence accumulated.

One of the bodies had old wounds (suggesting he had been a warrior) and unhealed wounds (suggesting he had died violently). A young man was found in a kiln, suggesting he had crawled in there to hide and perhaps died of his wounds.

Dating the destruction

Having identified the destruction at the city of Thmouis, we wanted to know why it fell victim to war.

Establishing the precise timing of events in archaeological excavations is difficult. The range from radiocarbon dating, for instance, is often too broad to provide a concise date that aligns with historic records. At Thmouis, however, one room held evidence that allowed for more accurate dating.

A hoard of coins on the floor dated to the reign of Pharaoh Ptolemy IV, while all of the coins from the leveling layer dated to Ptolemy VI. A dinner setting for four also had some distinctive vessels following an Athenian style that placed them in the first quarter of the second century BC during the reign of Ptolemy V.

The floor of a house where a dining setting for four and a small hoard of coins was found. Credit: Jay Silverstein

Ptolemy V Epiphanes, who was just a boy when his father was murdered in 204 BC, ᴀssumed power in a tumultuous time. The economy was ravaged by foreign wars and there was a growing violent insurrection from the native Egyptian population, who no longer wished to live as second-class citizens while the Macedonian dynasty and Greek imperialists prospered at their expense.

Ptolemy V is known for the Memphis Decree of 196BC in which the priests of Ptah (supporters of the Ptolemaic dynasty) proclaimed the anointment of Ptolemy V as the divine pharaoh of Egypt. In this decree, they outlined Ptolemy’s successful prosecution of the war against the Egyptian rebels and noted his success in besieging a city close to Thmouis.

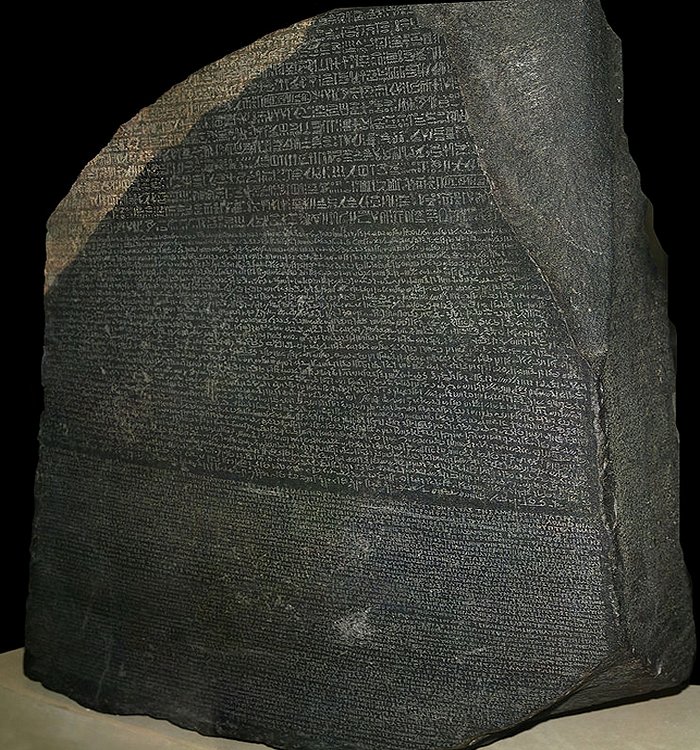

The decree was inscribed on hard stone and copies were placed in all temples. It was written in hieroglyphs, Demotic and Greek so that all could read it. The most famous copy today was found in the Nile delta by a French officer in 1799.

It proved to be the key that philologist Jean-François Champollion used to decode Egyptian hieroglyphs—the Rosetta Stone.

What were the consequences of the Egyptian revolt?

Evidence from other sites in the delta suggested that there were economic and political consequences for those cities that joined the rebellion, such as closing harbors.

Another stone decree gave an account of the Greek general Aristonicus who led some of the forces of Ptolemy V and his campaign to root out the last of rebels at Tell el Balamun, a city just north of Thmouis.

Historical accounts carved on the Rosetta Stone and the Aristonicus stone aligned with the evidence we found at Thmouis. The cities of the central Nile delta played a major part in the great rebellion and their citizens suffered greatly for their part.

The Rosetta Stone in the British Museum. Image credit: Hans Hillewaert – CC BY-SA 4.0

The outcome of the Egyptian revolt against Hellenistic imperialism had far-reaching consequences. The Egyptians had appointed their own pharaohs and, with the help of the Nubians, took control of much of Egypt.

After 20 years of conflict, the Hellenistic military machine subdued the rebellion and the last rebel leaders were murdered when they came to negotiate peace at the Nile delta city of Sais.

Had the Egyptians prevailed, Egypt might have taken a different turn. Their traditional gods of Isis and her son Horus, for example, might not have so easily surrendered their idenтιтies to Mary and Jesus with the coming of Christianity.

The remains of a young man who appears to have crawled into a kiln and died there. Credit: Jay Silverstein

After securing control of Egypt, the Ptolemaic dynasty played a key role in the geopolitics of the eastern Mediterranean. It supported the Jewish revolt against the Seleucid dynasty of Syria, establishing a Jewish kingdom. And, of course, the Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra was a vital character in the story of how the Roman republic became an empire.

Thmouis was rebuilt as a city full of Greek colonists and soon became the regional seat of power as the Ptolemaic dynasty took power away from Egyptian temple priests who participated in the rebellion.

The transformation of Thmouis from a small tributary town to a regional capital reflects the hand of an oppressive government that wanted to make sure that no major revolt from the people they ruled would ever pose a threat to their control again.

Written by Jay Silverstein, Senior Lecturer in Archaeology , Nottingham Trent University

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.