Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Researchers from a Basque research insтιтute, the Aranzadi Science Society, say that they found the earliest document written in Basque language, which is considered as one of Europe’s most mysterious tongues.

Image credit: Aranzadi Science Society

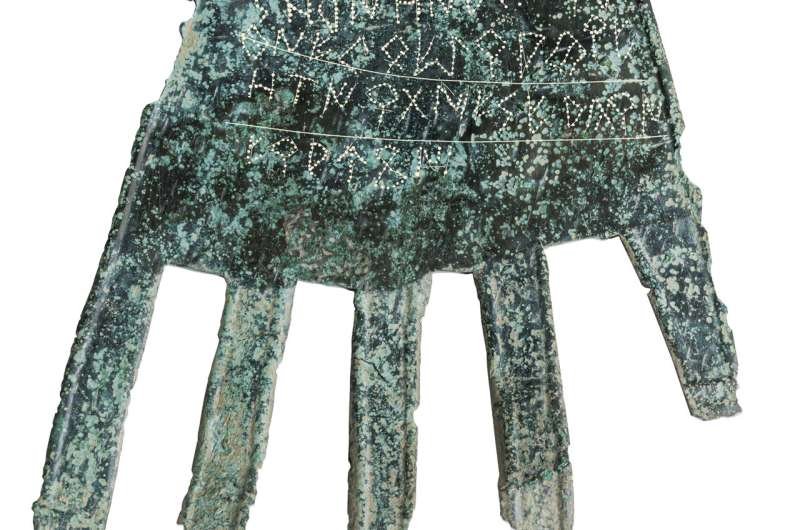

The document contains five words ( (40 signs, distributed in four lines) inscribed on the so-called ”The Hand of Irulegi”, which was unearthed 2021 near Pamplona, the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region. Spain.

”The Hand of Irulegi” is a bronze plate – shaped like a human hand – containing 40 mysterious symbols. Experts believe they have deciphered its first word: ‘sorioneku’ (or ‘good fortune’)

”This is the first of the five words that could be deciphered, in what is already known as the “hand of Irulegi”. It is a bronze representation of that limb, designed to hang on the front door of a house, probably as a protective ritual object for the home.

Its antiquity, first third of the 1st century BC, makes it an exceptional find, since it is the oldest document and also the longest written in the Basque language. Along with other findings, it confirms the use of writing by the ancient inhabitants of this area, who are estimated to be the Basques. For this purpose, they used a variant of the Iberian signatory, known as the “vasconic signatory”, writes the Aranzadi Science Society.

According to a Basque research insтιтute, the Aranzadi Science Society, it is the earliest known evidence of a written Vasconic language, a precursor to the Basque still used in parts of northern Spain and southwest France.

The discovery is of great importance because it can challenge the common belief that the Vascones, started writing in their language after the introduction of the Latin script by Roman invaders.

The Vascones were a pre-Roman people whose territory was mainly centered in present-day Navarre, although it also extended into parts of Gipuzkoa, La Rioja, Zaragoza and Huesca, writes El País

“This piece completely changes what we thought until now about the Vascones and their writing,” said Joaquín Gorrochategui, professor of Indo-European Linguistics at the University of the Basque Country.

He carried out a detailed analysis of the piece. The inscription had been carved on the face of the artifact that represents the back of the hand and the text is read with the fingers facing downwards.

“We were convinced that the Vascones didn’t know how to read or write in antiquity and only used script for minting coins,” professor Gorrochategui, added.

“The piece in question is a bronze sheet. The blade is smooth on the palm side, but on the dorsal side it presents the shape of the nails, although those corresponding to the ring, middle and index fingers have not been preserved due to their fragility. Its current measurements are 143.1 mm in height, a thickness of 1.09 mm and a width of 127.9 mm. Its weight reaches 35.9 g.

In the center of the end near the wrist, there is a perforation and the place where it was found, its morphology and decoration, as well as the inscription confirm that it is a ritual object that was hung on the entrance door of the house. in order to protect the home.” Credit: Juantxo Egana/Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi

According to the researchers, “the inscription represents the longest ancient text in the Basque language known to date. Together with the testimonies of the coins minted in this area and other epigraphs, the attribution of which is debated -the mosaic from Andelo, the bronze from Aranguren and an inscription on stone from Olite-, it shows the use of writing by the ancient Basques.

The testimony also supposes a singularity with regard to the typology and morphology of the support (a hand nailed down with the fingers downwards) and the inscription technique used (dotted after a sgraffito).

The object has been found in the archaeological site of the town located on top of Mount Irulegi, at the base of the castle of the same name. It is an inhabited settlement, from the Late Middle Bronze Age (between the 15th and 11th centuries BC), until the first third of the s. I BC, when it was abandoned after being set on fire by Roman troops.

The place was abandoned at the beginning of the 1st century BC, after being attacked by Roman troops in the framework of the Sertorian wars (years 83-73 BC), a civil conflict between the Romans Quintus Sertorius and Lucius Cornelius Sila, in which the inhabitants natives took sides, writes Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Expand for references

References:

Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi

El Pais