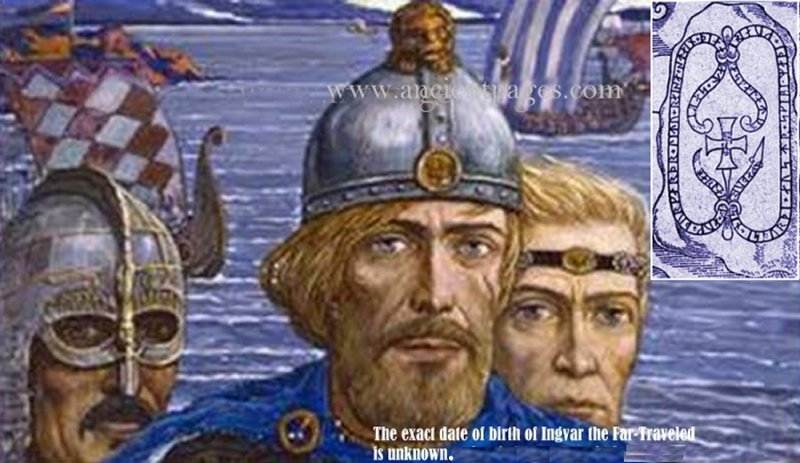

A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – Ingvar Vittfarne (in English: Ingvar the Far-Travelled) (ca. 1016-1041) was a Viking chieftain from Mälardalen (Malar Valley) in central Sweden.

The Icelandic saga of the Swedish Viking Ingvar the Far-travelled is believed to be a tale rather than an actual story based on facts.

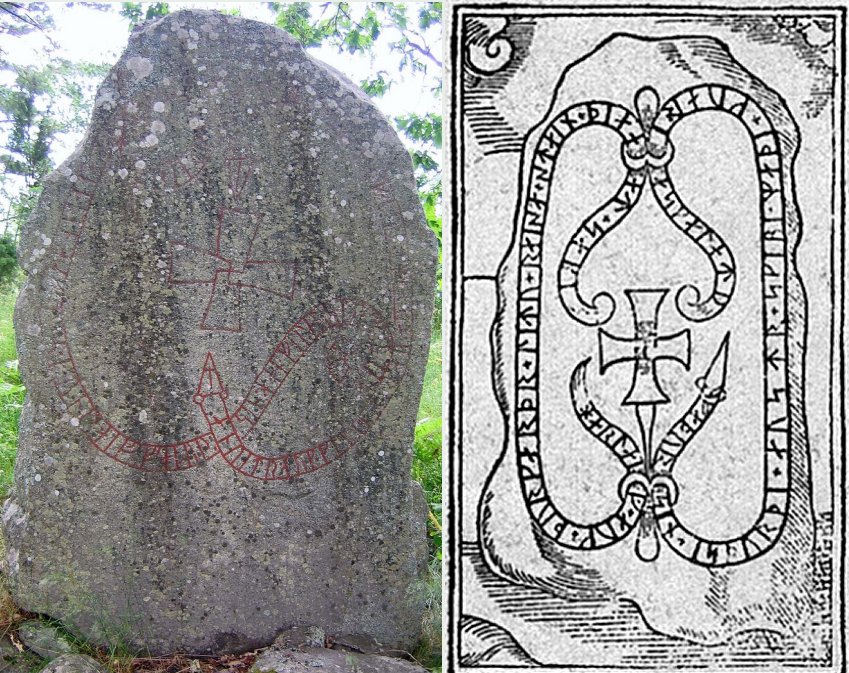

However, there are several fascinating runestones called Ingvar Stones in the provinces of Södermanland, Uppland, and Östergötland in central Sweden, which tell us the story of the great expedition into the East, led by the Viking chieftain Ingvar.

Around thirty Varangian Runestones, also called the Ingvar Runestones, were raised to commemorate those who died in the Swedish Viking expedition to the Caspian Sea of Ingvar the Far-Travelled.

The Ingvar expedition was the single Swedish event that is mentioned on most runestones. Twenty-four of these stones are standing in the Lake Mälaren region of Uppland, Sweden, and refer to Swedish warriors who went out with Ingvar on his expedition to the Saracen lands.

A stone to Ingvar’s brother indicates that he went East for gold but died in Saracen land.

The Tillinge Runestone in Uppland, raised by a man in memory of his brother who died in Serkland, ends in a prayer for the brother’s soul. This runestone may be one of the Ingvar Runestones. However, it does not mention Ingvar the Far-Travelled, the leader of a Swedish Viking expedition to the Caspian Sea. Therefore, it may be a memorial to any Varangian who died while in service in Asia.

Left: One of the Serkland runestones (drawing) – Runestone U 439. Image credit: Johannes Bureus (1568-1652) – Public Domain; Right: Runestone U 644 – is more than 2 meters high and was mentioned for the first time in the 17th century. Image credit: Berig – Ekilla Bro.

Besides the earlier mentioned and the one on Gotland, the Ingvar Runestones are the only remaining runic inscriptions that mention Serkland.

It was a fateful expedition between 1036 and 1041 with many ships. The Vikings came to the south-eastern shores of the Caspian Sea, and they appear to have taken part in the Battle of Sasireti in Georgia. Few returned, as many died in battle, but most of them, including Ingvar, died.

T. D. Kendrick, in his book “A history of the Vikings,” narrates:

“This incursion of the Vikings into the Caspian region was the far-famed expedition of the royal Swedish Viking Ingvar Vittfarne, whose illustrious name appears on more than twenty rune-stones in his country.”

“This prince, with a following of Swedes, made a daring voyage down the whole length of the Volga, fighting on the way, so his saga tells, dragons and serpents and monsters of all kinds, until at last he came to Sarkland where he died in the year 1041 at the young age of twenty-five.

A memorial stone in Södermanland is thus inscribed, ‘Tola set up this stone for her son Harald (or Havald), Ingvar’s brother; in far-off lands, they sought wealth boldly; in the east, their battles spread food before the eagle; south in Sarkland they died.’ (E. Brate, Runverser 84, p. 194 (A.T.S., x, 1887—91) ; for Ingvar, see F. Braun, Fornvännen, 1910, p. 99.) 1

In the eleventh century, Sweden once more found an occasion to seek wealth in the lands across the Baltic. “This was the time when Swedish traders made their settlements here and the time when Swedish buccaneering again distressed these coasts.

Seven Runic Inscriptions upon Swedish memorial stones of this period (1020–1060) tell of Swedes who fell in these countries.

In these decades, the royal Viking Ingvar Vittfarne descended upon and captured the western and southern coastlands of the Gulf of Riga. By 1070 Kurland, and probably Esthonia, were again under Swedish dominion, but it was not for long. Ten years later, Cnut II of Denmark plundered Kurland and Estland’. And again, after a short of Danish dominance, these regions pᴀssed into the keeping of their own Baltic folk.

Ingvar Vittfarne was about 25 years old when his ships left the country.

Runestone of Harald ( Sö 179 ) at Gripsholm, Södermanland, Sweden, one of the “Stones of Ingvar”. The inscription reads: “ Tola ordered this stone to be installed after her son Harald, brother of Ingvar. They bravely went far for gold and fed the eagles in the east. Died in the south at Serkland . » The text is written with the help of Kennings “to go for gold” – to participate in a Viking campaign and “to feed the eagles” – to kill enemies whose corpses will serve as food for the eagles. Image credit: CC BY-SA 3.0

Archaeologists have argued about the particular course of Ingvar’s voyage. The runestones are not specific, and the only written source that mentions the journey is a later medieval saga, in which the truth is difficult to determine.

Sources say that Ingvar, son of a Swedish prince and a great man named Eymundr, grandson of king Erik Segersäll (‘Eric the Victorious’), went with about 700 men in 30 ships to “Särkland.” It was the “land of the Serkir,” usually identified with the Saracens, mainly Arab Muslims, living south of the Caspian Sea, as also referred to by Christian writers active in Europe during the Middle Ages.

The runestones mention steer mates, captains, and navigators involved in the expedition. They also inform the ships were lost in Särkland, and none of the runestones confirm that anyone would have survived this incident.

The year of Ingvar’s death, 1041, according to the saga and the Icelandic annals, fits with the supposed age of these runestones.

Another important source is the Georgian chronicles’ Kartlis tskhovreba’ (The Life of Kartli), a collection of Georgian chronicles compiled in the 12th century and supplemented until the 19th century. This ancient source is divided into the Ancient Kartlis Tskhovreba and the New Kartlis Tskhovreba. The former covers Georgian history up to the 14th century, and the latter, from the 14th to the 18th century. Several manuscripts of the Ancient Kartlis Tskhovreba from the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries have been preserved.

The area around the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. Background image – FornVännen

These important Georgian chronicles mention Ingvar’s expedition from Sweden through the Russian Volga River to the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

However, it is not exactly known where the adventures of Ingvar and his men occurred. One theory on where Ingvar went is based on the runestones, the saga, and the Georgian annals. A study has found several similarities between the geographical location and a road through Georgia and the territories beyond the Caspian Sea.

The Vikings probably used small ships, which could be carried over the waters between the Rioni and the Kura valleys, the Suram pᴀss. The reason for the expedition could have been to open a new trade route to the Caspian, as the Volga was closed by the Tatarian tribes.

The annals also tell of Varangians participating in the war c.1040 between the Georgian king Bagrat IV and his vᴀssal Liparit. Ingvar and his men probably participated in the Georgian-Byzantine Battle of Sasireti, located about 6 km north of the Kura OEH, about 70 km west of Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the largest city in Georgia).

Georgian chronicles mention Ingvar’s expedition from Sweden through the Russian Volga River to Black Sea as well as the Caspian Sea.

It was a battle between two brothers who fought for power, and Ingvar Far-Traveled and his warriors supported one of them.

The runic inscriptions further say that Ingvar continued his voyage, probably to the land of the Abbasid Caliphate, with Baghdad as their capital around the Caspian Sea. On the way there, their ships were ᴀssaulted by pirates who had “big ship-like islands” from the fire hurled at them from a copper pipe. One of the ships burned, but they returned fire with their flaming arrows and went on across the Caspian Sea shortly before reaching Samarkand.

The fire against them was remarkable, for it burned even if it ended up in the water. It could happen in the so-called Nafta country, where rock oil and flammable gases suddenly appear out of the ground. Finally, the expedition seems to have experienced some terrible disaster, probably the plague, and only a few or none returned to Sweden.

Many years later, the parents and friends of those who died erected the stones that represent a tribute to this fatal expedition to the East, the Viking chieftain Ingvar and his men.

Written by – A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

References:

Riksarkivet

FornVännen

Svenska Runa Stenar

Föreningen Vittfarne