Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Oral hygiene was important to the Maya who had remarkable dental skills.

Scientists have discovered that the ancient Maya came with a special technique that may have prevented tooth decay.

In the beliefs of the ancient Maya, their breath was a link to the divine so it was important to be clean and fresh in the mouth. The purification process was accomplished by filing, notching, and polishing the teeth. It happened often that people polished and decorated their teeth with gemstones. To purify it, many people filed, notched, and polished their teeth, some even decorating them with gemstones.

Copy of Bonampak Painting in Chetumal. This is an artist’s copy of a mural at the Temple of the Murals at Bonampak, a Maya archeological site. The original murals are badly weathered and faded. Credit: Elelicht – CC BY-SA 3.0

“Now, a fresh analysis suggests the sealant used to hold these jewels in place may have had therapeutic properties, which could have helped prevent infections.

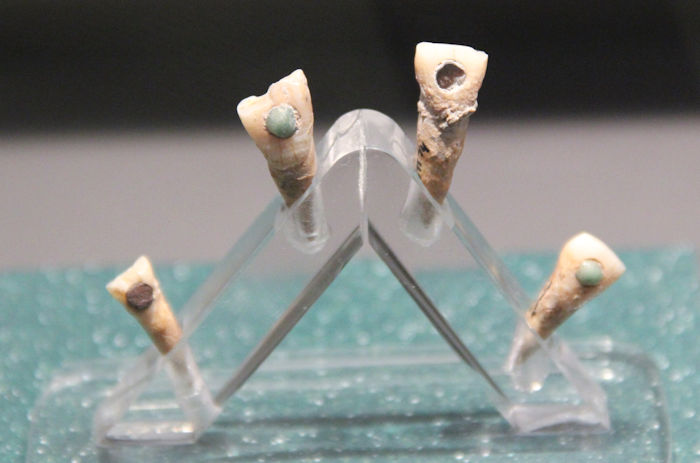

During the Classic period (200 to 900 C.E.), many lowland Maya people in what is now Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico affixed colored stones such as jade, turquoise, and pyrite to the front of their teeth. Maya dentists drilled holes into the enamel and dentine, then fit the stones and applied a sealant, usually as part of a rite of pᴀssage to adulthood.

This dental adhesive has proved remarkably durable: More than half of such modified teeth from archaeological digs still have their stone inlays intact. Previous analyses of the adhesive found inorganic materials similar to cement, and hydroxyapaтιтe, a mineral obtained from ground teeth and bones. These materials helped strengthen the mixture, but likely wouldn’t have been sticky enough to hold the stones in place. The nature of the binding agent has long been a mystery,” the American ᴀssociation for the Advancement of Science reports.

“One of the major unknowns regarding the ancient Maya practice of dental inlaying is the nature of the cement, used to affix small stones inside artificially drilled cavities on labial tooth surfaces. These cements endured the harsh buccal environment of a lifespan and secured the inlay firmly in the tooth even through centuries of subsequent postmortem decay. Beyond their adhesive properties, the sealant materials probably reduced cariogenic activity and periodontal infectious disease. Prior analysis of dental sealings was limited to the identification of inorganic components. Among the materials identified are hydroxyapaтιтe and Portland cement-related compounds, materials that hardened and strengthened Maya dental adhesives. However, the substances that provided the agglutinant and resistance properties to the sealants and fillings remain unknown,” the researchers write in their study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Gloria Hernández Bolio, a biochemist at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Insтιтute in Mexico and her team have conducted an analysis of the sealants in eight teeth found in burial sites across the Maya empire, and discovered two techniques were used to deal with dental problems.

In the examined sealants scientists found 150 organic molecules common in plant resins.

As explained by the AAS, “each sample had a binding component like plant resin or gum, which have also been used for their water-repelling and gluelike properties since antiquity. Statistical analysis revealed the sealants could be separated into four groups based on that location, suggesting local pracтιтioners each had their own recipes. The mixtures appear to have been well thought out, Hernández Bolio says. “Each ingredient has a specific task.”

Most samples included ingredients found in pine trees, which other research suggests can fight bacteria that cause tooth decay. Two teeth showed evidence of sclareolide, a compound found in Salvia plants that has antibacterial and antifungal properties, and is currently used as an aroma fixative in the perfume industry. Sealants from the remote outer Copán region, near the border of modern Honduras and Guatemala, included essential oils from mint plants whose components potentially have anti-inflammatory effects. This ingredient wasn’t found elsewhere, possibly reflecting connections with other Maya groups or traditions, the authors say.”

Cristina Verdugo, an anthropologist from the University of California, Santa Cruz said this study sheds light on the long-standing question of how these stones were affixed.

Not only were the Maya dentists good at their work, but they also knew “how to avoid potential unwanted side effects,” such as infection or other dental issues postmodification, she says.

Teeth from a young lowland Maya man found in present-day Guatemala, incrusted with jade and pyrite. Research suggests the sealant used to hold these stones in place may have had therapeutic properties. Credit: Public Domain

Hernández Bolio, whose grandfather is Yucatec, a group that’s part of the historic Maya civilization said his people use still use these plants for medicinal purposes. It is therefore very likely the ancient Maya were familiar with the benefits of these plants.

The AAAS reports, “Joel Irish, a dental anthropologist at Liverpool John Moores University, says he’d like to see more evidence concerning the antiseptic and therapeutic properties. “It is a key takeaway that relies on previous, though compelling, research.”

Oral hygiene was important to the Maya, says co-author Vera Tiesler, a bioarchaeologist at the Autonomous University of Yucatán. She points to Janaab’ Pakal, the Maya king of Palenque, who died in 638 C.E. at the age of 80 with nearly all his teeth and no signs of decay in those that remained—a tribute to the remarkable dental skills of his people.”

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer