A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – Tikal was the Maya’s religious, ceremonial, and military city-state, with a long and fascinating history recorded in the city’s ruins, artifacts, and plenty of stelae.

The elaborately carved wooden Lintel 3 from Temple IV. It celebrates a military victory by Yik’in Chan K’awiil in 743. Image credit: Jose Fernando – CC BY-SA 2.0

Tikal’s name is probably derived from ti ak’al in the Yucatec Maya language and means “at the waterhole.”

The city succeeded in its economy, military affairs, and religious importance. Located in the tropical forests of northern Guatemala, the city flourished between the years 200 and c.850 AD.

Tikal’s geographical location undoubtedly contributed to the city’s greatness.

Conquest Of Tikal To Remove And Replace Former Ruler By Sihyaj K’ahk’ – “Smoking Frog”

There is evidence that Tikal was conquered by the warlord Sihyaj K’ahk’ (literally, “born of fire”), usually identified by the nickname “Smoking Frog.”

The conquest occurred in the 4th century AD, more precisely in 378 AD. The ruler then was Chak Tok Ich’aak I (also known as Great Paw, Great Jaguar Paw I, Jaguar Paw III). He ruled from 360–378 AD and was a successful builder and an influential military leader.

Despite his achievements, Sihyaj K’ahk’ (probably supported by a powerful political faction at Tikal) wanted the king removed. He captured and executed him immediately.

Tikal, Guatemala: Stela 31 back. Image credit: HJPD – CC BY 3.0

Janice Van Cleve wrote in her book “Tikal’s stela 31 contains some of the most elaborate imagery and extensive text to be found on a single stela anywhere in the Maya world. The monument is today housed in the museum on the grounds of the Tikal archaeological park. It is actually a little small.

It stands approximately eight feet tall, making the figures carved on its sides roughly life-sized… It most likely stood before the steps of Tikal Temple 33 in the central plaza.”

Stela 31 was found deep inside temple 33 in a shrine just above the painted tomb of Siyaj Chan Kawil II, the 16th king of Tikal (411- 456 CE). Archaeologist Edwin Shook discovered the tomb during the sixth season of excavations by the Penn State Museum in 1961.

In an article тιтled “The Painted Tomb At Tikal,” Shook wrote:

“When the last offerings had been placed in the tomb, and the masons had finished their work…. its contents lay undisturbed in damp blackness until Shook looked through a hole in the walled entrance fifteen hundred and four years later.”

Left: Stela 31, with the sculpted image of Siyaj Chan K’awiil II. Image credit: Greg Willis – CC BY-SA 2.0; Right: Tikal, Guatemala: Stela 4. Image credit: HJPD – CC BY 3.0

He described the interior of the tomb, the offerings, the two sacrificed youths, and the condition of the king’s remains. The king’s body had apparently been placed in a sitting position Teotihuacano style, тιԍнтly wrapped in fabrics.

His head and hands were missing.” 1

Personally, Sihyaj K’ahk’ did not take the throne of Tikal for himself. Within a year, Sihyaj K’ahk’put a young boy, the son of the Teotihuacan emperor on the throne. This conquest was a significant event in Tikal’s history, commemorated on Stela 31 and several other monuments.

On stelae that were frequent in Tikal, the Maya recorded religious and historical events on stelae (tombstones or stone pedestals), erecting them in public areas. There were scenes of military victories, marriage alliances, and ascensions to the power of new rulers on these monuments.

Agriculture, Drinkable Water Thanks To Sand Filters

Agriculture production became prosperous due to the combination of extensive hydraulic works that made it possible to cultivate the marshy areas near the city of Tikal.

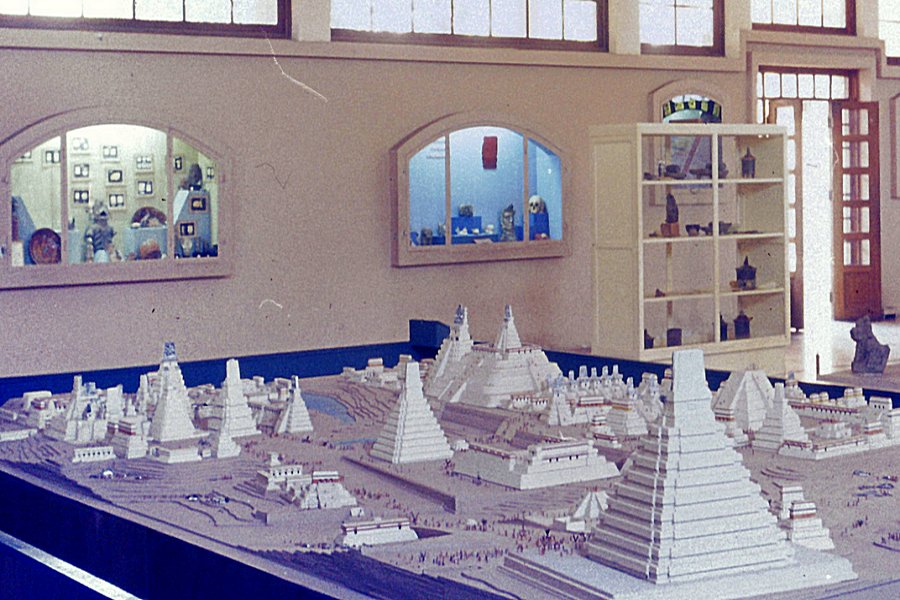

Model o the ceremonial center of the Maya city Tikal, National Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, Guatemala City. Image credit: Robert Schediwy – CC BY-SA 3.0

However, it was not a problem because the Maya were highly resourceful people and could handle well with water reserves; they also knew the soil, topography of the terrain, and periods of rain crucial for crops.

The Maya had a vast and impressive knowledge of hydraulic agriculture. The rain that fell during the wet season was significant, as was the water from all neighboring streams.

Around the 5th century, a unique fortification system consisted of ditches and earthworks. Surprisingly, many researchers consider these constructions well-developed water collection systems rather than defensive structures today.

The Mayan engineers used every terrain slope to connect the water reserves. Sand filters were widely used to clean the water to make it safe to drink.

Significant population growth at the time required well-organized agricultural production.

Maya agricultural development in the Tikal region could also be possible thanks to regular studies of the stars’ transit and systematic records in the solar and lunar calendars. These activities allowed correct planning of the people’s agricultural activities.

Constructions – Well-Planned, Reasonable In Size, And Very Solid

The Maya constructions were well-planned, reasonable in size, and solid.

Tikal (now partially restored) was one of the largest of the Classic period Maya cities and, simultaneously, one of the largest cities in the Americas.

The ancient city’s architecture includes the remains of temples that tower over 70 meters (230 ft) high, large royal palaces, many smaller pyramids, residences, administrative buildings, mᴀssive platforms for events, and inscribed stone monuments.

Interestingly, pyramid-shaped structures symbolized artificial mountains reaching for the heavens and connecting the earth with the underworld and heaven. The Tikal’s builders placed a temple on the top of the pyramid. Thus, the temple was closer to the heavens for the priests and kings to communicate with the gods. Also, those buried inside the pyramid could easily access heaven.

The primary material for the construction of temples and monuments was limestone. Lime was used to cover the facades of prominent temples.

The North Acropolis, Tikal, Guatemala. Image credit: Peter Andersen – CC BY 2.5

The ridges decorated the roofs of the temples to impress the people with the power of the rulers. Stucco decorations were added to them, painted mainly with deep red pigments.

Noteworthy were roads almost a kilometer long and 40 meters (131 ft) wide. By the middle of the 5th century, Tikal had a core territory of at least 25 kilometers (16 mi) in every direction and was still systematically increasing.

While Tikal flourished, it had approximately 100,000 citizens by 750 AD, and the city reached its apogee during the Classic Period (c. 200 to 900 AD.) Tikal’s core population and agricultural resources encircled approximately 120 square kilometers (46 sq mi).

Murals, Zapote Wood, Ballgame

Elaborate wood carvings were decorations of entrance doors to the temples. They were made of zapote, hard and resistant wood, carved using only stone tools. The zapote wood is still used for furniture, house building, floors, arches, etc.

Mayan murals have always been famous and covered the temples of the Mayan ceremonial centers, depicting religious rituals and celebrations of military conquests.

According to the Maya tradition, Tikal had seven courts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame, including a set of 3 in the Seven Temples Plaza, a unique feature in Mesoamerica.

In Tikal, many activities flourished, including hunting, collecting forest products, and cultivating maize, pumpkin, bean, potato, pepper, and other products necessary for daily needs and trade. The people enjoyed art, dance, literature, and weaving. Ceramics and sculptures, of which many examples decorate both international and local museums.

War And Expanding of Territory

Although the new rulers of Tikal were foreign, their descendants were Mayanized without delay. Strategically, Tikal became an important ally and trading partner of Teotihuacan. By the middle of the 5th century, it had a territory of at least 25 kilometers (16 mi) in every direction. Tikal’s stability and prosperity were long maintained despite local conflicts and other political problems with neighbors.

The Maya established well-functioning and extensive international networks in the Mayan zone and beyond, in particular with the great city of Teotihuacan.

Decline Of Tikal

Following the end of the Late Classic Period, no new major monuments were erected at Tikal, and there is evidence that elite palaces were destroyed. These events were connected with a gradual population decline and the site’s slow abandonment by the end of the 10th century.

The collapse of Tikal, one of the most powerful kingdoms of the ancient Maya, still needs to be precisely discovered. The subject has long been discussed, and many theories have been proposed.

Written by – A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Updated on January 3, 2024

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

References:

Harasta J. Tikal: The History of the Ancient Maya’s Famous Capital

Harrison Peter D. The Lords of Tikal

The Most Famous Cities of the Maya: The History of Chichén Itzá, Tikal, Mayapán, and Uxmal