Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash – AncientPages.com – Mystery creates wonder, and wonder is the basis of man’s desire to understand. – Neil Armstrong, Astronaut

Why Are Egyptian Obelisks A Mystery?

Obelisks trigger acute fascination owing to their intriguing symbolism, awe-inspiring size and significant challenges presented when creating, transporting and erecting monuments of such large scale. At the time of ancient Egypt, and according to Labib Habachi, it was the ability of obelisks to embody a complexity of meanings that ensured they held great significance in the lives of the people. Since that time, the question of how the obelisks were raised grew to be a marvelous and peculiar riddle that has continued to baffle people for centuries. Even today, with continued global interest and numerous theoretical explanations and practical attempts, researchers are still not clear on how it was achieved.

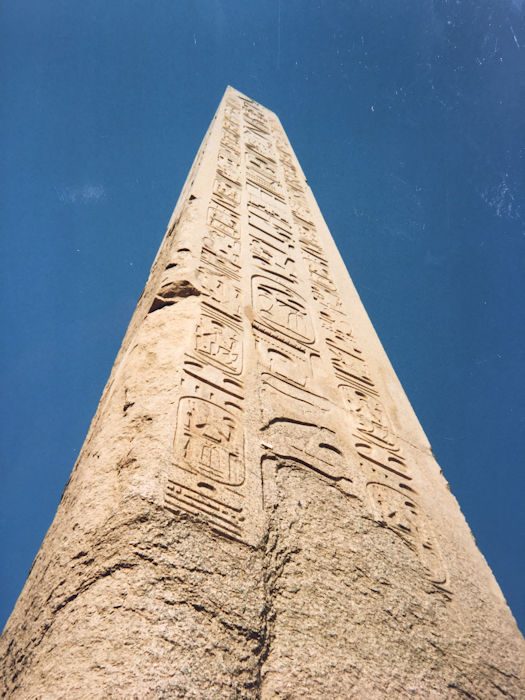

- Hatshepsut’s Obelisk at Karnak Temple. Built in 1457 BC, the obelisk is 97 feet tall and weighs 357 tons. Credit and copyright: Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash

An obelisk is a rectangular stone pillar with a tapered top in the shape of a small pyramid. It was the Greek historian Herodotus that coined the name, although the Egyptians called them techn(u) or tekhen(u) – to pierce (the sky). Author Joshua Mark points out that “although many cultures around the world… employed the obelisk form, only ancient Egypt worked in monolithic stone”. Primarily found standing on a pedestal in temple complexes, in identical pairs [1] of similar weight and height, obelisks varied in scale from small funerary stones to towering monoliths made of red Aswan granite. Referring to the obelisk at Luxor Temple, Classical Scholar George Long gives us an idea of their powerful presence: “Of all the works of Egyptian art which, by the simplicity of their form, their colossal size and unity, and the beauty of their sculptured decorations that excite our wonder and admiration, none can be put in comparison with obelisks”.

2. The Unfinished Obelisk at Aswan. Commissioned by Hatshepsut, this monolith was intended to be 137 feet high and1170 tons in weight. Had it not cracked, this obelisk would have been the largest and heaviest obelisk ever erected in Egypt. Credit and copyright: Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash

To the ancient Egyptians, inventor of the form, obelisks were a solar cult symbol that glorified the powerful importance of the sun. At Heliopolis, twin obelisks were built to honor the sun gods and the pyramidon tops were capped in gold to symbolize both the sun’s splendor and make contact with the divine. Each obelisk was carefully raised and positioned so the first and last light of day would touch their lofty peaks.

Symbolically, obelisks also embodied the creation myth of Heliopolis, a story that describes how the sun god Atum called out for life and light while standing on a primordial mound that emerged from a formless swamp of raw potential. The pyramid-shaped top of the obelisk represents this moment of creation – the birth of the world. According to Brian Curran, obelisks were also a symbol of the Pharaoh’s right to rule and connection to the divine. It was their geometric genius, stylistic perfection, monumental dimensions and precision engineering that ensured the pharaohs, royal authorities and priesthood adopted obelisks as important tools to ᴀssert their status.

Engelbach Theory: In The Problem of Obelisks (1923). English engineer Reginald Engelbach proposed several obelisk-raising ideas. One theory involved dragging an obelisk up a ramp using rollers and a sled and lowering the obelisk down into a funnel-shaped pit where, aided by stabilising ropes, it came to rest on a pedestal. Credit and copyright: Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash

Obelisks were also wonders of engineering. Weighing up to four hundred tons, they were cut from the bedrock as a single stone block, shaped and smoothly finished, and transported and erected at important sites throughout Egypt – a remarkable achievement when considering the simple technologies available in ancient times.

For astronomer Gerald Hawkins, their singular nature was of significant importance: “The obelisk had to have been made in one piece, monolithic, because it was levered up into position as a telephone pole might be set up in a hole in the ground”. No doubt the Egyptians learned about the practical need to work within the limitations of granite through trial and error so as to avoid cracking the monolith. For the last three millennia, these obelisks stood tall and strong and proved, even by today’s standards of technology, that they “still bear witness to their former skill, might and piety”, as stated by Labib Habachi. It is likely that the ancient Greeks, upon first encountering obelisks in Egypt, shared the same awe and admiration that we still feel for these marvels of civilization today. Out of the original twenty obelisks in Luxor’s Karnak Temple, only three remain standing on site today.

Raising Obelisks: Our Theoretical Clues

Making and moving an object of this size is a highly challenging undertaking, and it is still not clear how it was achieved. From theoretical speculation to practical experimentation, in back gardens and commercial quarries, and using a variety of materials and approaches, scholarly investigators and maverick engineers have researched and developed their ideas with one goal in mind – to conclusively answer the question: How did the ancient Egyptians raise their colossal obelisks? Our curiosity sparked, we joined the list of researchers seeking to answer this fascinating riddle.

Conceived in 1999, our theory was slowly brought to life conceptually and experimentally over the following years. We reviewed previous research, publications, resources and documentaries, and immersed ourselves in the remarkable nature of this ancient civilization, the historical significance of obelisks, and previous obelisk-raising theories and attempts. What became clear was that to the best of our knowledge, no solution had been proposed that conclusively answered the question of how obelisks were raised in ancient Egypt. Indeed, we recognized that some theories ended up raising more questions than providing answers, and that previous expertise on the subject tended to suffer from many historical and theoretical ᴀssumptions. Our insights into existing phenomena lead us to three breakthroughs in our thinking around the raising of obelisks.

Firstly, Duality as represented by a set of scales. Pharaohs were all too familiar with the dualistic nature of life, demonstrated in their kingship of the two lands of Upper and Lower Egypt [2] and their twofold existence as divine and human. Egyptian beliefs also held that opposing polarities of light and dark could be brought into balance in the face of chaos and disorder, and in this way stability and order was maintained. Key to our theory is the fact that obelisks throughout Egypt were most frequently found at major sites in pairs – even if they now stand separately around the world in far off locations such as London, Paris, Rome and New York.

Secondly, Simplicity as represented by a feather. Using systems thinking, we identified a holistic yet simple method, a technique not misguided by complicated engineering or historical ᴀssumptions but guided by the principles of ma’at in action. We identified the many ways in which the goddess Ma’at (truth, simplicity, beauty and balance) and the moral code of ma’at (right order in life; balance and perfection) were present in their lives, duties and business relations. A sense of ma’at ensured the harmonious balancing of opposites which was essential to their daily, worldly and other worldly sense of overall stability and cosmic order.

Palm Fibre Rope: The making of strong rope from the triple twining of palm tree fibres can still be seen in Egypt today. Credit and copyright: Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash

Thirdly, Circularity as represented by the divine order of life. Ancient Egypt was a practical and inventive culture that made the most of locally available materials. For example, the common palm tree was a valuable resource for shelter, shade, food and household articles, as well as being used to make ropes and rollers to move large objects. We hypothesized that an incredibly strong rope net, coiled and woven from date palm fronds, could have played a key role in raising obelisks, particularly when used alongside lever thinking, counterpoise and the natural laws of gravity,

By broadening our context, we began to see the ways in which every aspect, detail, part, whole and interdependency of their lives was considered to perfection, on a micro and macro level, from the commonly available date palm tree to the monumental act of raising the obelisks, to the eventual building of an extraordinary civilization. The technique for raising obelisks that we propose is simple, even obvious in nature, and might be better described as a long forgotten ancient Egyptian invention. Indeed, its simplicity could alter the preconceptions we hold about the ancient Egyptian mindset and the knowledge, engineering and systems thinking abilities they possessed at that time. As we continued to find supporting evidence, we evolved a mental image of our hypothesis. The big challenge was becoming clear. If we conducted a real life, at scale experiment, would it work in practice?

Raising Obelisks: Our Practical Experiments And Future Directions

In order to put our ideas to the test, we devised a series of practical experiments. Archaeology is the model for a form of historical research that brings to light unremembered facts from the past. Our intention was to use applied research and build three different scales of working models to demonstrate and evidence our ideas in action, using only the materials available during ancient Egyptian times.

The first experiment was conducted in 2016, and this and each successive experiment was visually recorded. The successful results proved that the method works in practice, at scale, to raise obelisks, and we believe this process was the one used in ancient times to raise full size Egyptian obelisks. To the best of our knowledge, this process has not previously been attempted, and it is our ambition to conduct a full-scale experiment. This is not without complication and with sufficient support, we hope to put our ideas to the test at full scale.

Our intention in sharing this research is to (1) evidence our somewhat alternative process and results, (2) share the results and catalyze peer and public discussion, and (3) disseminate our findings and contribute to the body of knowledge regarding obelisk-raising. We believe our findings are significant in how they shed new light on current ᴀssumptions we hold about the history of ancient Egypt and the knowledge and engineering skills possessed at the time.

Raising Obelisks: Unearthing a Long Forgotten Ancient Egyptian Invention by Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash by Kathryn Best (academic, author, architect) and Mahmoud Al Hashash (independent egyptologist ) offers a thought-provoking account of their recent investigation into how obelisks were raised in ancient Egypt, a story which concludes with the raising of several obelisks at scale in Luxor, Upper Egypt, using only the resources, materials and technologies available in the past.

By offering a fresh perspective on the exceedingly difficult task of obelisk-raising, the authors also hope to spark curious interest and further investigation into the ᴀssumptions we hold about the ancient Egyptians and the level knowledge and skills they possessed at the time. The book is available on Amazon USA and Amazon UK.

It is our ᴀssertion that the ancient Egyptians had more know-how than currently ᴀssigned and propose the necessity of revisiting common knowledge views within Egyptology and in particular, in the words of Gadalla, to acknowledge the spiritual intent behind the symbolism, the ritualistic nature of daily life and the thoughts and beliefs behind the built and written forms of expression therein. It was the role of the pharaoh to commission and build architectural and engineering wonders in honor of the gods (glory), to reign over the two kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt (unity), and to ensure the harmony of opposites (duality) throughout the two lands – so preserving and reflecting ma’at in everything that occurred as a manifestation of heaven on earth.

With regard to our proposed ideas for how these architectural and engineering wonders were raised, it may well be impossible to ever conclusively prove that this method was the technique used in ancient Egypt, since no records exist, however, we welcome open-minded critical debate on our published ideas and welcome the opportunity to raise full-size obelisks.

Written by Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash – AncientPages.com

Copyright © Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash – AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of Kathryn Best and Mahmoud Hᴀssaan Al Hashash and AncientPages.com

Expand for references

References

Brian Curran, Anthony Grafton, Pamela Long and Benjamin Weiss. Obelisk, A History. Cambridge MA: MIT Press / Publications of the Burndy Library, 2009.

Moustafa Gadalla. Egyptian Cosmology: The Absolute Harmony. Erie PA. and Cairo: Bastet Publishing, 1997.

Gerald S. Hawkins. Beyond Stonehenge. New York: Harper & Row, 1973.

George Long. Egyptian Antiquities, Volume 1. London: The British Museum, 1832.

Joshua J. Mark. Egyptian Obelisk, Ancient History Encyclopedia. Published 06.11.16.

Labib Habachi. The Obelisks of Egypt-Skyscrapers of the Past. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1977.