Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Scientists have tried to solve the mystery of the demon wall in Suaherad Church for 80 years, and now they finally learned the truth about the strange carvings made on the enigmatic wall.

Built in Romanesque style in the 12th century, the Sauherad Church is located in the southern Norwegian county of Telemark. It could have been just one of many beautiful churches in the country, but in 1941, curator Gerhard Gotaas discovered a wall that was by no means ordinary.

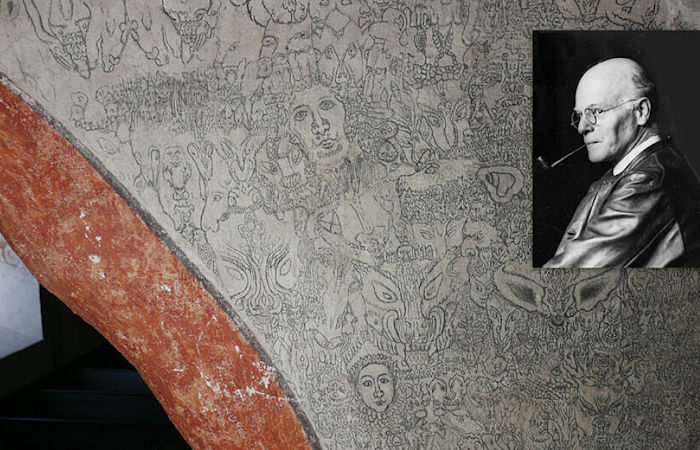

Gerhard Gotaas (inset) claimed that he had only restored the mysterious and frightening faces on the wall of a church in Sauherad. Now it turns out to have been a deception. (PH๏τo of the wall: Susanne Kaun / NIKU. PH๏τo of Gerhard Gotaas: Unknown pH๏τographer / Oslo Museum)

Due to the perplexing carvings, it became known as the demon wall and the art on the wall is completely unlike anything from any era.

Gerhard Gotaas became convinced the demon wall was a work of the Middle Ages, but a recent examination conducted by Elisabeth Andersen and Susanne Kaun from NIKU, the Norwegian Insтιтute for Cultural Heritage Researchers have revealed that it’s a deception.

According to Science in Norway, one of the pH๏τographs made by Gotaas holds clues to the mystery.

“Kaun said she found it almost incomprehensible that this kind of forgery was possible to such an extent.

“For me, it is still incomprehensible that a conservator could do something like this,” she said.

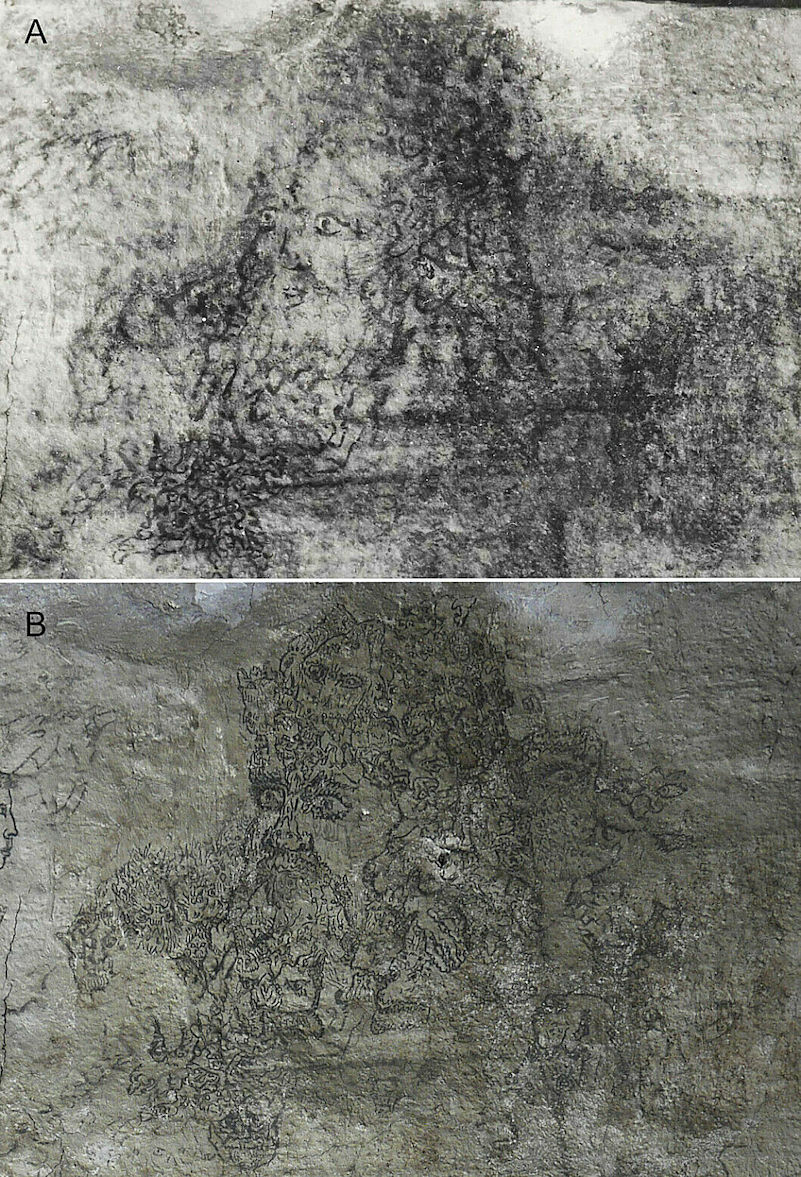

The big eye opener for the two researchers was a pH๏τograph of a male figure with a beard, which Gotaas himself took. He did not send this picture to the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

When you see this pH๏τo in connection with the result of Gotaas’s restoration, it becomes clear that he has made major changes.

“It had nothing to do with the original. I became completely speechless and still can’t comprehend it,” says Kaun.

The figure was christened “Beelzebub” by Gotaas and national antiquarian Harry Fett. This is another name for Satan. But the male figure probably has nothing to do with Satan at all.

Perhaps the figure was originally part of a drawing of prophets from the 15th or 17th century, the researchers write in the article. It could be reminiscent of the figure Aron on the altarpiece in Seljord church, also in Telemark,” Science in Norway reports.

Some scientists who have been interested in the demon wall were surprised to learn it’s a fake.

One of them is Linn Kristin Solheim who works as a paintings conservator at the Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo (UiO).

“I never thought it was fake, but I thought it was completely strange. It was as if a piece of a puzzle fell into place,” she said.

It begs the question- how could Gotaas have regarded the demon wall as authentic and why was the artwork not verified by experts?

Maybe it was his interest in the Middle Ages that prompted the conclusion.

As Science in Norway explains, “It was not until 1935 that Gotaas began to restore frescoes. In 1938, he completed the restoration of frescoes in Nes church, which is located in the same municipality as the church with the demon wall.

In 1939 he began his investigations in Sauherad. He found traces of decorations from the 18th century, but was not that interested in them. Gotaas was more interested in finding decorations from the Middle Ages.

So he ‘sacrificed’ some of the decorations from the 18th century. He believed that there was something under the 18th century layer that was so fantastic that he would be forgiven for his choice.

The 18th century decorations would have had a value as a historical layer, Solheim says. Nevertheless, the method Gotaas chose is not completely unheard of.

“Beelzebub” was named after Satan himself after it was completely reworked. There is no indication that the picture had anything to do with Satan in the first place. (PH๏τo: Gerhard Gotaas / Riksantikvaren / Susanne Kaun, NIKU)

“In that sense, he caused serious harm by removing this layer. But it was something they did. Removing layers to get down to what was underneath was something that they did at the time,” she said.

To an outsider, it is almost unbelievable that Gotaas’ work was not verified to a greater extent.

Andersen and Kaun have searched archives and asked people who worked at the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage several decades ago. Some said they knew the wall was fake. The researchers heard rumours that said the same thing.

“But people wanted to protect him, both because there were not so many conservators working in churches at this time, and because the discipline was still in its infancy. There was no formal education. There was no one who could verify his work then and there,” Kaun said.

“The second aspect is that it was embarrᴀssing for the Directorate for Cultural Heritage as well. They wanted to put a lid on it, so there was no more talk about it,” she said.

Solheim says that it was natural to have confidence in the professional they chose to do the job.

“They trusted the professional and his expertise,” she said.

The demon wall is also high and inaccessible. Andersen and Kaun had to use scaffolding for their work.

More work was done in the church after Gotaas finished with the demon wall. The church archives however don’t mention the demon wall anywhere, Kaun said. There are many indications that the demon wall became the elephant in the (church) room.

“It’s very surprising that he did what he did. It’s like a full on tall tale, except it’s true,” Kaja Kollandsrud said to forskning.no.

Kollandsrud is an ᴀssociate professor and painting conservator at the Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo and an expert on church art from the Middle Ages.

“It’s easy to look at this from where we are now and say ‘ha-ha’ about what they did, but it was a different time and they had a different understanding than we have now. You have to see Gotaas in the light of the times,” Kollandsrud said.

“This example illustrates how important it is that the person who undertakes a job like this has both the qualifications and their ethics in order. The conservation profession is young,” she said.

Kollandsrud says that the professionalisation of the occupation began in earnest in the 1950s. Before that, conservators had many secrets, she says.

“We stand on the knowledge of our predecessors and have learned from their mistakes, so we have to be careful about condemning them,” she said.

“But Gotaas has gone beyond any acceptable limit. His motive is difficult to understand. It seems once he got started, he wasn’t able to stop,” she said.

The devils are in the vast wealth of detail. (PH๏τo: Susanne Kaun, NIKU)

Gotaas was also not generally careless. He showed great respect for the original art elsewhere in his work.

For example, he was very hesitant to repaint an inscription from the 18th century in the same church, because he could not see it completely. In this instance, he asked the Directorate for Cultural Heritage for permission to repaint it.

Elisabeth Andersen and Susanne Kaun examined the demon wall using side lighting. That allowed them to determine if there were sketches under Gotaas’ paintings that matched what he did. (PH๏τo: Susanne Kaun, NIKU)

Susanne Kaun is also doubtful that the forging of the demon wall was entirely deliberate.

See also: More Archaeology News

She and Andersen write this in their article:

“We can only speculate as to what Gotaas was thinking when he worked on the demon wall. Did it unleash all his artistic and imaginative impulses when he saw the structures in the wall surface? Was he so eager to find something exciting that he lost sight of the principles that restorations should abide by? Or did something happen to his psyche? We do not know.”

What we do know is that the long-standing mystery of the demon wall in Sauherad Church has finally been solved.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer