Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Scientists have studied how ancient people responded to catastrophic natural events and discovered ancient Maya people used volcanic ash to build some of their pyramids.

According to Akira Ichikawa, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado Boulder excavation and radiocarbon data reveal the Maya survivors and/or re-settlers made considerable efforts to construct monumental public buildings immediately following the eruption of Tierra Blanca Joven at San Andrés, El Salvador.

The recent study published by Cambridge University Press shows “such re-building played important religious, social and political roles in human responses to the eruption.”

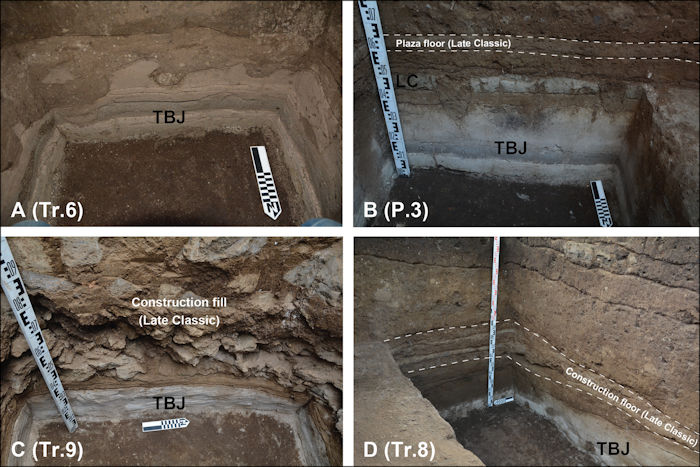

Tierra Blanca Joven tephra identified at San Andrés, showing different thickness of tephra found in different excavated areas: A) Trench 6 located in the Campana structure; B) Pit 3 located in the North Plaza; C) Trench 9 located in Structure 10; D) Trench 8 located in Structure 6 (pH๏τographs by A. Ichikawa).

The date and impact of the TBJ eruption have long been a controversial topic among archaeologists. This recent study suggests the eruption occurred AD 539/540, but there are also scholars who think this natural catastrophe happened earlier.

The Tierra Blanca Joven eruption has been of great interest because it was the largest volcanic eruption in Central America over the past 10,000 years, and the largest on Earth over the past 7,000 years. The blast was powerful volcanic ash spread over 35 kilometers.

This eruption affected the Mayan civilization and people have to leave the region quickly. Scientists have long debated how long it took for the Maya to return to the area. It was ᴀssumed they came back after hundreds of years, but new research reveals the Maya people returned soon and used volcanic ash to build pyramids.

In their science papers, researchers explain “the survivors and/or re-settlers in the Zapoтιтán Valley may have constructed the monumental public building at San Andrés in response to the mᴀssive TBJ eruption. As others have this work might have had a religious purpose, enabling social integration, as well as creating a sense of community among participants during the difficult times following the eruption. Furthermore, local leaders or rulers may have emerged and reinforced their own power through this construction process.

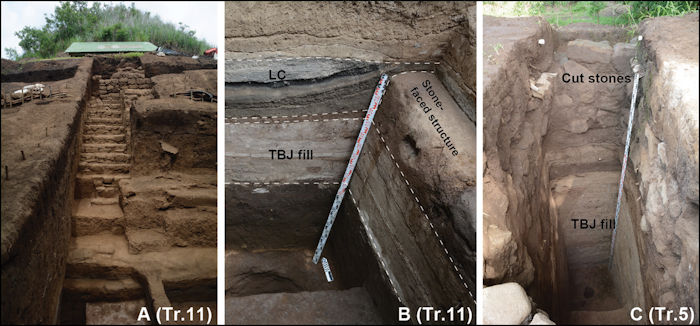

Stone-faced structure at San Andrés: A) central staircase; B) stratigraphic relationships between the primary Loma Caldera layer, the stone-faced structure and the TBJ fill; C) large quanтιтy of TBJ fill under the cut stone blocks (pH๏τographs by A. Ichikawa).

The devastating first-century AD eruption of Popocatépetl in Puebla, Mexico forced a population movement; these refugees contributed to developing the largest urban centre of Mesoamerica: Teotihuacan but whereas Teotihuacan was developed by displaced migrants in an area unaffected by the eruption, San Andrés was transformed into the valley’s primary centre by returning survivors and/or re-settlers.

Notably, an increased investment in monumental public buildings at San Andrés was also observed after the Loma Caldera eruption. The total volume of the Acropolis (processed using Surfer software) is 91 757m3—almost three times the total volume of the Campana structure.

The structure was built using large quanтιтies of adobe, indicating more intensive labour investment than required in the previous period. Radiocarbon and stratigraphic data show that the Campana structure was renovated using new adobe and mud-plaster construction techniques.

The Acropolis and other adobe structures were also constructed in the decades immediately following the Loma Caldera eruption, and San Andrés became the primary centre of the Zapoтιтán Valley.

See also: More Archaeology News

Presumably, San Andrés may have been a focal point of the materialized memory of previous catastrophic eruptions and regional, community idenтιтy. This phenomenon suggests an objective of future research should be investigation of the potential correlation between the volcanic eruption and political and economic processes.

Mᴀssive volcanic eruptions may have directly or indirectly changed the course of Mesoamerican history, as well as that of other ancient civilizations.”

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer