A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – The Old Testament mentions the city Uruk as Erech, and its original Sumerian name is Unug. What we know today about Uruk comes from archaeological excavations at the site, whose modern name is Warka.

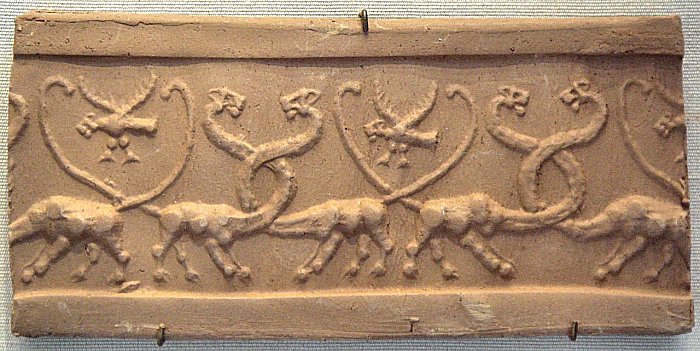

Clay impression of a cylinder seal with monstrous lions and lion-headed eagles, Mesopotamia, Uruk Period (4100 BC–3000 BC). Louvre Museum. PHGCOM – CC BY-SA 4.0

The oldest settlement was built in this place during the Ubaid period (5000 BC) in the 5th millennium BC. Between 4000 and 3000 BC, Uruk became Mesopotamia’s most extensive and influential city. Initially, it occupied an area of approximately one hundred hectares (one square kilometer) and continued to develop until it reached around 400 hectares.

According to the Sumerian King List, Uruk was founded by King Enmerkar around 4500 BC and was the largest settlement in southern Mesopotamia, if not the world. King List adds that Enmerkar brought the official kingship with him from E-ana after his father Meskiaggasher, son of Utu, had “entered the sea and disappeared.” Enmerkar founded Uruk, the largest settlement in southern Mesopotamia, around 4500 BC, and was said to have reigned for “420 years” (or even “900 years”).

In “Sumerian Mythology,” Samuel Noah Kramer writes that one (unpublished) tablet that was unearthed in Nippur says that “hero Enmerkar ruled in the city of Erech sometime during the fourth millennium BC.”

Did Enmerkar exist, or was he a legendary figure? Today, it is hard to say.

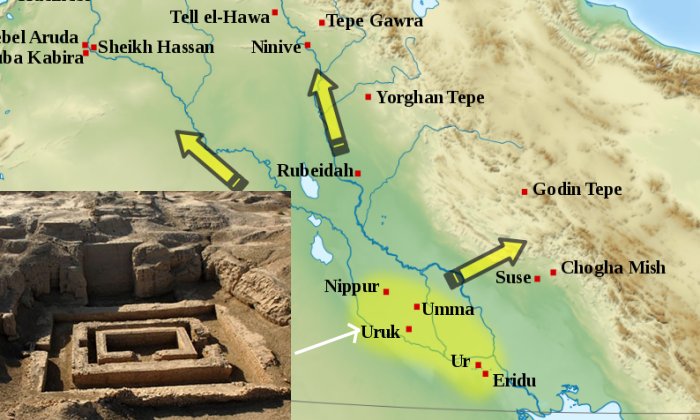

In his book “Sumerians,” Henry Freeman writes that “the city “may have been the largest in Mesopotamia, if not the world, in 3200 BC. Generally, the Uruk expansion into Susa, east of Uruk in Elam, is interpreted as a colonial takeover. Uruk also expanded into Northern Syria and Anatolia in the Northern Highlands circa 3700 BC… The Uruk cultural expansion made it to Nineveh in the north, Suse in the east, and the Anatolia area.” 1

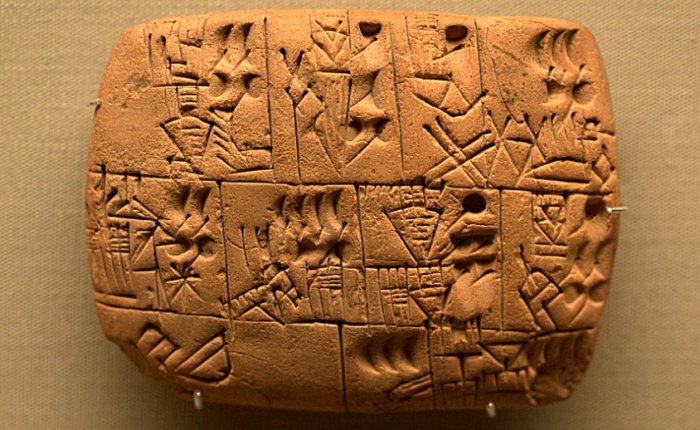

Tablet from Uruk III (c. 3200–3000 BC) recording beer distributions from the storerooms of an insтιтution, British Museum. – CC BY 2.0

In the first half of 3000 BC (the Early Dynastic Period), the residents of Uruk probably began to construct a defensive wall of dried brick. According to an ancient imprint of the cylindrical seal, the city’s strong wall measured nine kilometers (was continually repaired and strengthened) and effectively surrounded Uruk, giving the inhabitants good protection.

Tradition has it that the great hero Gilgamesh (the son of the mortal Lugulbanda and a minor goddess, Ninsun) contributed to this achievement.

With time, Uruk became the most important city-state and commercial, cultural, administrative, and cultural center in southern Mesopotamia. Likewise, it was also a significant political and economic power in the region. Its influence extended to northern Syria in the west and Iran in the east. The world’s first known writing system – pictographic writing contributed to Uruk’s power

It originated from the Near Eastern token system used for accounting and was used in Uruk at the end of 4000 BC and then spread throughout Mesopotamia.

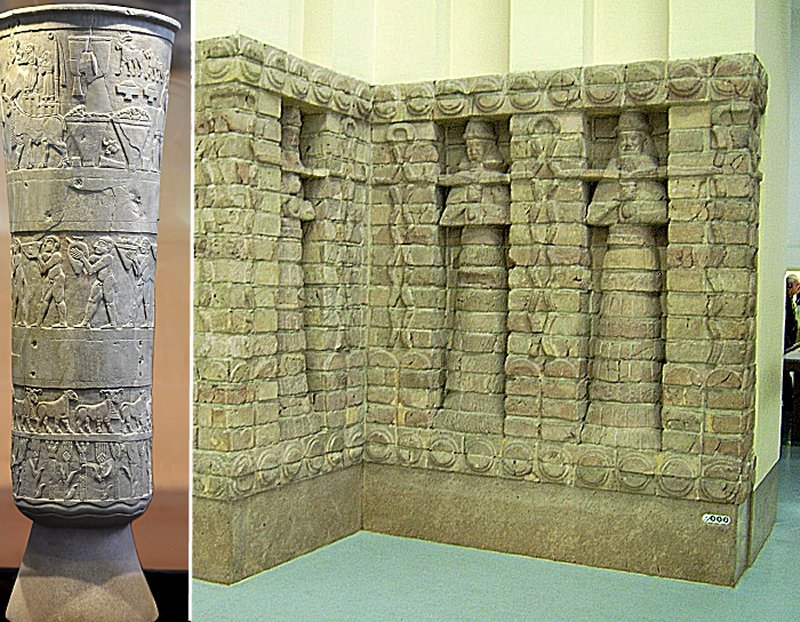

Left: Devotional scene to Inanna, Warka Vase, c. 3200–3000 BC, Uruk. This is one of the earliest surviving works of narrative relief sculpture. source; Right: Part the front of the Inanna temple of the Kara Indasch from Uruk. source

Left: Devotional scene to Inanna, Warka Vase, c. 3200–3000 BC, Uruk. This is one of the earliest surviving works of narrative relief sculpture. source; Right: Part the front of the Inanna temple of the Kara Indasch from Uruk. source

In the famous “Epic of Gilgamesh,” the city of Uruk is described as follows:

“The outer wall shines in the sun like the brightest copper; the inner wall is beyond the imagining of kings. Study the brickwork the fortification; climb the great ancient staircase to the terrace; study how it is made; from the terrace, see the planted and fallow fields, the ponds, and orchards. One league is the inner city, another league is orchards; still another the fields beyond; over there is the precinct of the temple.

Three leagues and the temple precinct of Ishtar measure Uruk, the city of Gilgamesh….’

Later, the city gradually began to lose its importance, and then again in the Neo-Sumerian Empire (circa 2112 BC – circa 2004 BC ), the rulers of the 3rd dynasty of Ur contributed with new construction projects that included the ziggurat of the goddess Inanna who was highly honored in Uruk, especially in the Eanna temple complex (meaning the “House of Heaven.”)

The guardian god of Uruk was An, but later, his cult was replaced by the cult of Inanna; therefore, there were two sacred complexes in the city. One was E-Anna, dedicated to Inanna, and Kullaba, dedicated to the god An.

Decline Of Uruk – Ancient Ruins Tell About The City

Several factors contributed to the fall of the city of Uruk. Among them was the invasion of Sumer by the Elamite civilization, the incursions of the Amorites, an ancient Semitic-speaking people who dominated the history of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine from about 2000 to about 1600 BC, and, of course, the fall of the third dynasty of Ur. Uruk once again began to lose its population and importance. Finally, the city became part of the state of Larsa.

It is worth mentioning that Uruk – unlike many other cities in Mesopotamia, was not abandoned when its inhabitants observed the city’s gradual decline. The abandonment first occurred due to the Muslim Conquest of Mesopotamia in 630 AD.

William Kennett Loftus (1820-1858), a British geologist and excavator, carried out the first archaeological excavations at the site of Uruk. In 1850-1854, he discovered its ruins, excavated clay tablets, and mapped the area. Many other researchers later worked at the site, and they could shed much light on Uruk’s distant past.

However, did they answer a question asked by Henry Freeman in his book?

Why did the Uruk expansion seem to have ended relatively abruptly in 3100 BC with the abandonment or destruction of Uruk settlements in Syria, Anatolia, and the Zagros mountain area?

Written by – A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

References:

- Freeman, H. Sumerians

Macleod, Kezip. Legends of Sumer

Kriwaczek, P. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization