Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Who was the first explorer to visit the Arctic? That is a question one cannot answer quickly. The lack of historical references dealing with early Arctic exploration and difficulties interpreting early maps and accounts of voyages pose a challenge to our understanding of the historical period during which explorers reached the region north of the Arctic Circle.

Also, exploring dangerous territories like the Arctic may end with death. There could have been many people who traveled to the Arctic but never survived to tell their story.

Pytheas of Mᴀssalia (350 B.C. – 285 B.C.) described his voyage to the Arctic in a work that has not survived. Can his claims be substantiated?

He also reported a strange land in the North that is today referred to as Thule. Where could this mysterious land be located?

Pytheas was a Greek geographer, explorer, and astronomer. Today, he is considered the first known scientist who visited and described the Arctic, polar ice, and the Celtic and Germanic tribes. Being a good astronomer, Pytheas was also the first person to provide the world with a description of the Midnight Sun.

Pytheas’s Account Of Thule Fascinated People

The accounts of Pytheas were for centuries discredited, but the idea of Thule captured the imagination of many who longed to learn more about this mysterious land in the North.

“Since classical times, Thule marked the imaginative horizon of the unknown North, first described by Pytheas of Mᴀssalia, who in the third century B.C. reported on a strange place far north (‘six days sail north of Orcades’) where the sun would never set in the summer and where the ocean was solid frozen. Nobody knows for sure how far north Pytheas went himself and how much he relied on secondary knowledge in his own (lost) descriptions of this place.” 1

Pytheas stated Thule was inhabited by people whom he called the Hyperboreans. He also said they live on an island located to the North of Britannia. It is a place “beyond the north wind.” Later Greek and Roman authors such as Pliny, Pindar, and Herodotus described the Hyperboreans as happy people who had exceptionally long lifespans and did not suffer from illness.

“With shining laurel wreaths about their locks (of hair), they hold feasts out of sheer joy. Illnesses cannot touch them, nor is death foreordained for this exalted race,” Pindar wrote about the Hyperboreans 2

Pytheas introduced the idea of distant Thule to the geographic imagination, but the island he spoke about has never been located despite the clues left by the Greek explorer.

Ancient Greeks’ Knowledge Of Life In The North Was Limited

“When Pytheas set out from Mᴀssalia no one in the Greek world knew answers to questions like: How far north could people really live? How cold would it really get? Could the trend for increasing length of days during the summer extend to 24-hour sunlight? Was there a place beyond which climate improved again, a climate in which the Hyperboreans could be living? Could the world have an ‘edge’ at all?

Pytheas’ answers to these questions were so out of keeping with the established beliefs of Classical Europe that his critics labelled him a fabulist and a charlatan. He denied the misconceptions of the North then currently held in Greece, such as that one-eyed Arimaspians danced with the Hyperboreans there, and stole gold from the nests of gryphons. He said that on the contrary the Britons were people like the Greeks.” 3

Map showing the hypothetical route followed by Piteas. The most doubtful sections of the route are marked with a broken line. It is unknown how far north he sailed. Credit: Fschwarzentruber – CC BY-SA 4.0

Pytheas’s accounts of Thule led to countless speculations, and the idea that Thule was located on the northern edge of the inhabited world persisted.

“It was invariably where an “other” people lived as seen from the heartland of classical civilization. In the early Middle Ages, when Irish hermits and Norse Vikings began roaming the North Atlantic, Thule became located in Iceland, which was then as far as actual knowledge of the northern horizon went. When, soon afterwards, the settlers in Iceland had established their own canons of civilizations and moved onwards to “discover” Indians and Eskimos beyond the immediate horizon, the image of the northern barbarians once again was relocated.” 1

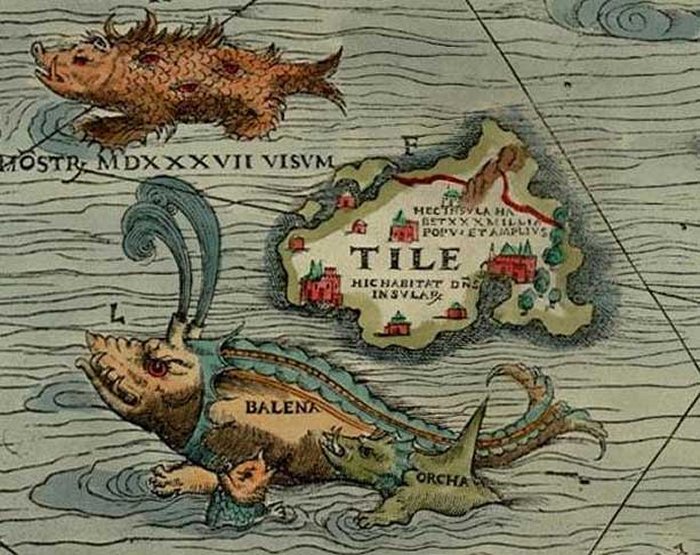

Thule as Tile on the Carta Marina of 1539 by Olaus Magnus, where it is shown located to the northwest of the Orkney islands, with a “monster, seen in 1537”, a whale (“balena”), and an orca nearby. Credit: Public Domain

From the day Pytheas of Mᴀssalia mentioned Thule for the first time, explorers have attempted to find this mysterious land, but all failed. Countless books have been written about Thule, each author, and researcher presenting their theory trying to explain the location of Thule. No one knows where this land exists or if it exists at all. There is today a place called Thule Island. Named after Captain Cook during his second voyage in 1775, it is one of three southernmost islands in the South Sandwich Islands. Still, this was not the Thule Pytheas described.

Pytheas’s descriptions of foreign lands he visited may not have been 100% accurate, but what can one expect from an explorer of the 4th century who did not have access to detailed maps. Pytheas of Mᴀssalia contributed with information expanding our knowledge of geography, and many consider him the first known explorer in the modern sense of the word.

Updated on October 8, 2022

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

- Hastrup, Kirsten. “Ultima Thule: Anthropology and the Call of the Unknown.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Insтιтute13, no. 4 (2007): 789-804.

- The Northern Lights Route – The Council of Europe Cultural Routes: The voyage of Pytheas to Thule. University Library of Tromsø

- Francis Gavin – True North: Travels in Arctic Europe