Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Archaeologists have tried to unravel the mystery of the giant Laos jars for some years, and now they report new, interesting discoveries.

As Ancient Pages reported earlier, “it’s important to mention that similar very large stone jars were found in Sa Huynh in Vietnam and also in the North Cachar Hills of northeastern India, more than 600 miles to the northwest, had roughly the same design and dimensions as the urns in Laos.

Site 2 Jars. The jars are believed to have been used for funerary purposes. Credit: PJARP

The jars of Laos are one of archaeology’s enduring mysteries. Experts believe they were related to the disposal of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, but nothing is known about the jars’ original purpose and the people who brought them there.”

Mysterious gigantic jars of unknown origin have been discovered worldwide, not only in Laos. Obviously, these huge stone jars must have been important to various different ancient cultures, but why?

In March this year 2021, scientists explained they are using a technique called Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) to determine when sediment grains were last exposed to sunlight researchers analyzed samples from the Laos jars.

“With these new data and radiocarbon dates obtained for skeletal material and charcoal from other burial contexts, we now know that these sites have maintained enduring ritual significance from the period of their initial jar placement into historic times,” Dr. Louise Shewan from the University of Melbourne said.

Dr. Shewan and her team revisited Site 1 (Ban Hai Hin) that revealed more burials placed around the jars and confirmed earlier observations that the exotic boulders distributed across the site are markers for ceramic burial jars buried below.

Researchers have now investigated more jars and discovered some of these buried ceramic vessels contain the skeletal remains of infants and children.

Although ceramic jar burials are known throughout Southeast Asia dating from around 2250 BCE, and archaeologists have found other examples in Laos in the 1980’s—this was the first time the Laos ceramic jars were shown to contain human skeletal material.

Based on these findings scientists ᴀssume the mortuary activity at the site was much more complex than previously thought, featuring three types of ritual—primary burials (where the skeleton is laid out), secondary burials (bundles of bones) and the ceramic jar burials.

Buried ceramic jars at Site 1. Credit: PJARP

Archaeological investigations at the site have been difficult to carry out due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the Lao-Australian archaeological research team has collected skeletal, ceramic and sediment samples for dating and isotopic analysis, as well as precious bronze artifacts that will be conserved at the University’s Grimwade Center for Cultural Materials Conservation.

Based on previous studies, scientists suggest the jars were placed at the site potentially as early as the late second millennium B.C.

“We used Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) to date the sediments beneath the jars, which gives us an estimate of when sediment was last exposed to light.

Until now, we could only guess at when the sites may have been created and the jars positioned by studying the artifacts found around the jars.

Our aim is to now use this method at some of the other sites, where the stone source isn’t found in the immediate vicinity of the site,” the science team explained in a press statement.

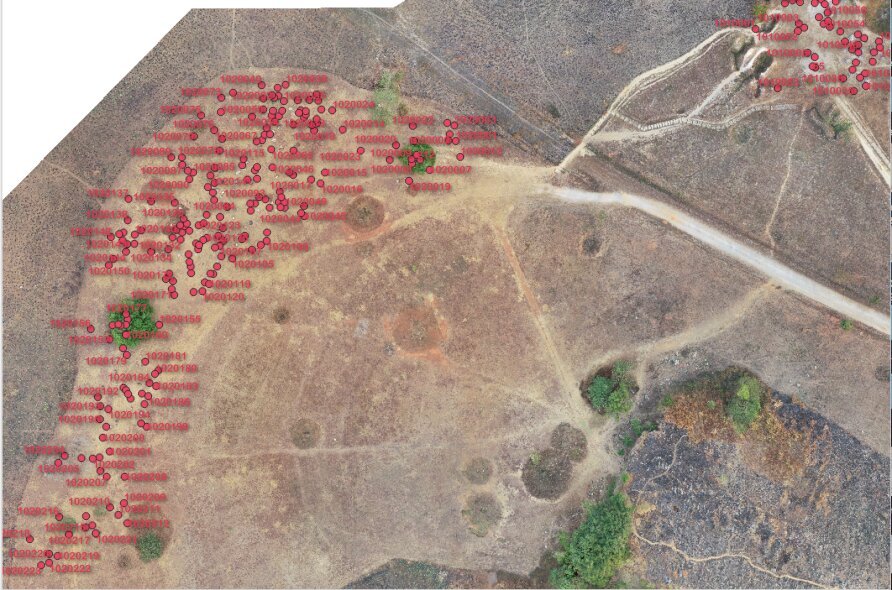

Extensive UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle or drone) mapping of Site 1 was also completed in 2020.

This has created of a high-resolution 3D map of the area, recording the precise position of each of the 316 individually numbered jars.

Dr. Thonglith Luangkoth, the project co-director from the Laos Department of Heritage and his team can now cross-check the condition of the sites and jars against an extensive repository of pH๏τographs, 3D models, and morphological data curated by the team over the past few years.

Since scientists cannot be at the sites, the data on the platform can be updated as more discoveries are made, allowing research to continue during this period of restricted international travel.

“Our team is hoping to return to Laos when international travel resumes after the pandemic. In the meantime, we have plenty of analyses to complete including the isotopic analysis from the recent excavations, dating of ceramic sherds and the conservation of bronze artifacts which will be returned to Laos for display in the Xieng Khouang museum.

Excavations at Site 2 suggested the jars were placed there potentially as early as the late second millennium BCE. Credit: PJARP

When we combine these results with the radiocarbon dates from the burials at Site 1, (known as Ban Hai Hin) – the most visited of the 11 UNESCO World Heritage listed jar sites estimated to be between the 8th and 13th centuries CE, this indicates that the sites have maintained cultural significance for a considerable amount of time,” researchers explained.

Scientists also added, their “team is hoping to return to Laos when international travel resumes after the pandemic. In the meantime, we have plenty of analyses to complete including the isotopic analysis from the recent excavations, dating of ceramic sherds and the conservation of bronze artifacts which will be returned to Laos for display in the Xieng Khouang museum.

A digitized map of jar locations at Site 1. Credit: University of Melbourne

When we combine these results with the radiocarbon dates from the burials at Site 1, estimated to be between the 8th and 13th centuries CE, this indicates that the sites have maintained cultural significance for a considerable amount of time.

Our research also details geochronological studies of jar and quarry samples used to determine the likely source of stone for the jars at Site 1.

Using U-Pb zircon dating, a method used by geologists to identify source rocks and their ages, zircon grains from a jar at Site 1 were compared to a sandstone outcrop and an unfinished jar from a presumed quarry around eight kilometers away from Site 1.

See also: More Archaeology News

All three samples revealed identical age groupings suggesting they have a very similar provenance and that the outcrop (at Phou Kheng or Site 21) was the likely source of the material used for the jar at Site 1.”

One big question is still unanswered. How the jars were moved from the quarry to the site remains a mystery.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer