Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com – By modern definition, a tyrant is a cruel and oppressive ruler hated by most people.

Peisistratos was a tyrant, but this doesn’t mean he was a bad ruler and was certainly not despised by the people. On the contrary. He was immensely popular among poorer people because he did not hesitate to confront the aristocracy. He was a fair ruler who boosted the city’s economy and spread wealth equally among the Athenians.

Unlike many other rulers, Peisistratos did not seize power violently. Instead, he used a cunning and funny way to convince people he was their ideal ruler.

Born in 608 B.C. in Athens, Peisistratos was a one-time brother-in-law of Cleisthenes, an ancient Athenian lawgiver credited with reforming the consтιтution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508 B.C. He was also related to the Athenian statesman, lawmaker, and poet Solon.

In 565 B.C. Peisistratos successfully managed to capture the port of Nisaea in nearby Megara. This victory made him famous, and he gained support from the Men of the Hill, the poorer and the majority of the population.

First Attempt To Trick The People Of Athens

Peisistratos way to power was not easy, and he encountered many obstacles. According to ancient Greek historian Herodotus, Peisistratos deliberately inflicted wounds on himself and his mules to demand from the Athenian people bodyguards for protection, which he received.

In The Histories, Herotodus writes: “…he inflicted wounds upon himself and upon his mules, and then drove his car into the market-place, as if he had just escaped from his opponents, who, as he alleged, had desired to kill him when he was driving into the country: and he asked the commons that he might obtain some protection from them, for before this he had gained reputation in his command against the Megarians, during which he took Nisaia and performed other signal service. And the commons of the Athenians being deceived gave him those 67 men chosen from the dwellers in the city who became not indeed the spear-men 68 of Peisistratos but his club-men; for they followed behind him bearing wooden clubs. And these made insurrection with Peisistratos and obtained possession of the Acropolis.

Then Peisistratos was ruler of the Athenians, not having disturbed the existing magistrates nor changed the ancient laws; but he administered the State under that consтιтution of things which was already established, ordering it fairly and well.

The Athenians celebrating the return of Peisistratos. Ellis, Edward Sylvester, 1840-1916; Horne, Charles F. (Charles Francis), 1870-1942 – The story of the greatest nations, from the dawn of history to the twentieth century (published in 1900). Credit: Public Domain

However, no long time after this the followers of Megacles and those of Lycurgos joined together and drove him forth. Thus Peisistratos had obtained possession of Athens for the first time, and thus he lost the power before he had it firmly rooted.

But those who had driven out Peisistratos became afterwards at feud with one another again. And Megacles, harᴀssed by the party strife, 69 sent a message to Peisistratos asking whether he was willing to have his daughter to wife on condition of becoming despot.”

Second Attempt To Trick The Athenians Using Goddess Athena

Peisistratos did accept the arrangement, but he wanted people to see him as the best choice to be the ruler of Athens.

So, Peisistratos came up with an idea. One day, he rode into the city with a tall, young girl, claiming that she was goddess Athena, the patron goddess of Athens.

Amazed people watched as their magnificent goddess, dressed in full armor riding a golden chariot along the streets yelled to the onlookers: “”O Athenians, receive with favor Peisistratos, whom Athene herself, honoring him most of all men, brings back to her Acropolis.”

As Herodotus explained: “So the heralds went about hither and thither saying this, and straightway there came to the demes in the country round a report that Athene was bringing Peisistratos back, while at the same time the men of the city, persuaded that the woman was the very goddess herself, were paying wor-ship to the human creature and receiving Peisistratos.”

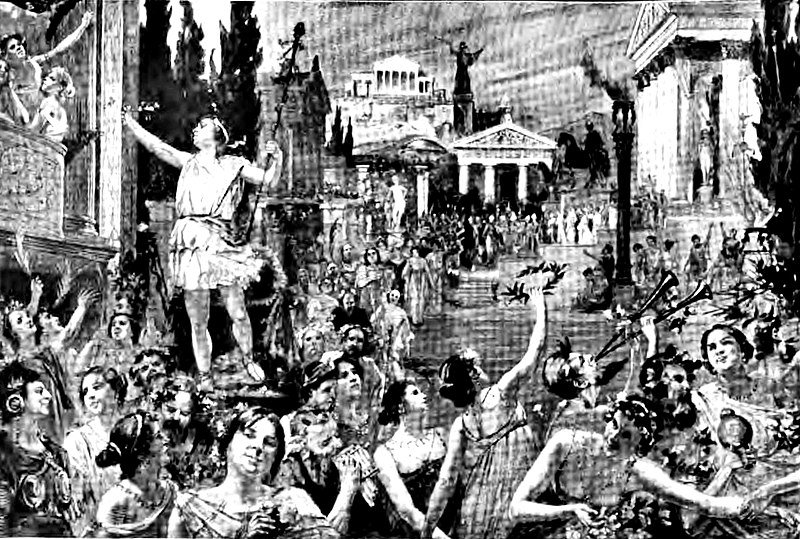

Illustration from 1838 by M. A. Barth depicting the return of Peisistratos to Athens, accompanied by a woman dressed as Athena, as described by the Greek historian Herodotus. Credit: Public Domain

The young woman was, of course, not the goddess Athena. She was a girl raised in a nearby village, but people embraced Peisistratos as their new ruler. Whether the Athenians knew this woman was not the goddess Athena is unknown. Some people may have suspected this was a clever political maneuver to gain power, and his efforts paid off.

One can say his means were dishonest, but his leadership was better than most in those before the birth of true democracy. He used his power in a favorable way with the aim of turning his people into his allies, especially the working class.

In Athens, Peisistratos’ public building projects provided jobs to needy people while simultaneously making the city a cultural center. Peisistratos ignored the ruling aristocracy. Instead, he focused his attention on helping poorer people by reducing their taxes and giving them free loans to help them build up their farms. He improved not only the city’s economy but also Athens’s infrastructure.

With its water supply and situation, Athens was greatly improved during the rule of Peisistratos through the construction of an aqueduct. The tyrant knew that access to water was a basic human need, and people were delighted they could have water to drink, cook, and clean.

There is no doubt Peisistratos did much to help Athens prosper, and he was a man loved by the common people. When he died sometime around 527 – 528 B.C., he was succeeded by his eldest son, Hippias, who was also a tyrant. However, Hippias was a paranoid and oppressive ruler, and he never gained the same popularity as his father once had.

Updated on December 23, 2022

Written by Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com