Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Hadrian’s Wall, also known as Picts’ Wall, Vallum Hadriani (in Latin), or simply the Roman Wall, is one of the most impressive Roman remains in Britain and the ancient site is investigated by archaeologists who keep finding artifacts in the region.

Hadrian’s Wall was built by the emperor Hadrian who visited Britannia in AD 122 and ordered his generals to build a wall from the banks of the River Tyne near the North Sea to the Solway Firth on the Irish Sea.

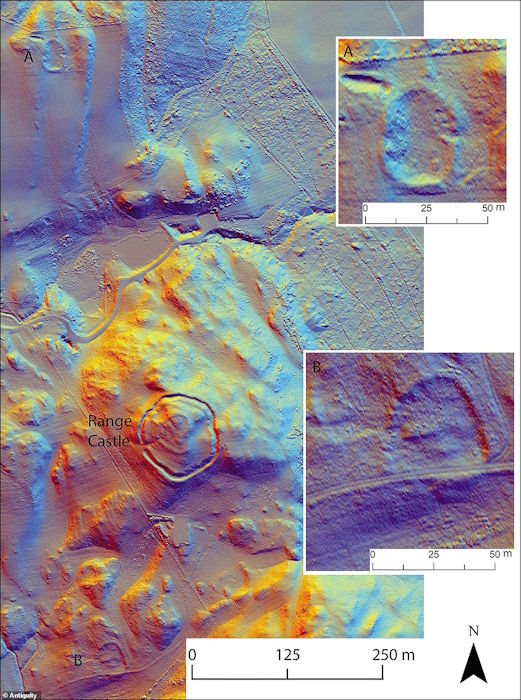

Credit: Antiquity

The construction would prevent raiders from the north from destroying the strategic Roman base at Corbridge, in Northumberland. As explained earlier on AncientPages.com, “Hadrian’s famous construction consists not just of the Wall itself, but a number of structures such as forts, bridges, towers, temples, civil settlements, and mile castles (small guard posts) with two turrets built at each mile, and many other constructions.

The structure was 80 Roman miles (about 73 modern miles or 117 km) long. It was built in 5-mile stretches, with seventeen forts. Smaller forts were built every mile and between these were signal turrets.”

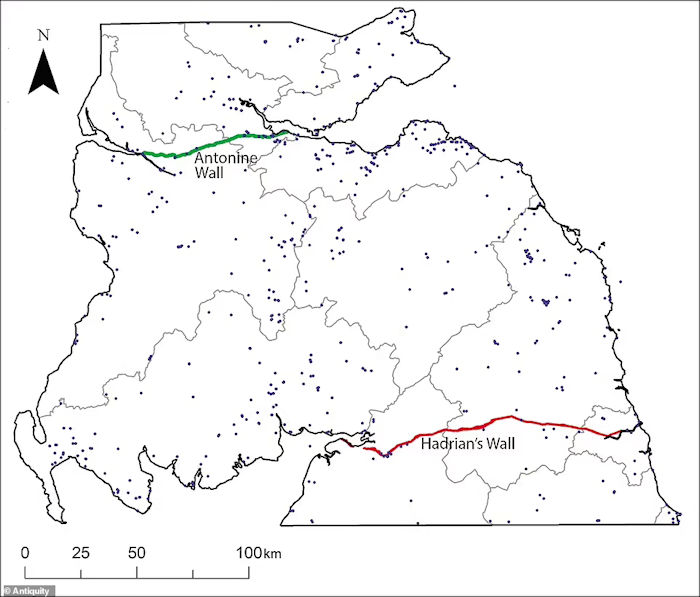

Archaeologists now report the discovery of more than 130 new indigenous settlements north of Hadrian’s Wall from the time of Rome’s occupation.

The archaeologists have been expanding beyond Burnswark, studying LiDAR data (pictured) from the surrounding 579 square miles (1,500 km2) with the support of the British Academy. Credit: Antiquity

Although part of the area had been extensively studied in the past, the team discovered 134 previously unrecorded Iron Age settlements in the region, bringing the total to over 700.

Most research regarding this region has been focused on the Roman side of the story to learn more about their roads, forts, camps and the iconic walls they used in their quest to control northern Britain.

“This is one of the most exciting regions of the Empire, as it represented its northernmost frontier, and also because Scotland was one of very few areas in Western Europe over which the Roman army never managed to establish full control,” said lead author Dr. Manuel Fernández-Götz, from the University of Edinburgh.

“So it’s a great case study to analyze the impact of imperial powers on societies at the edges of their political borders — a theme that is also relevant for later periods in history.”

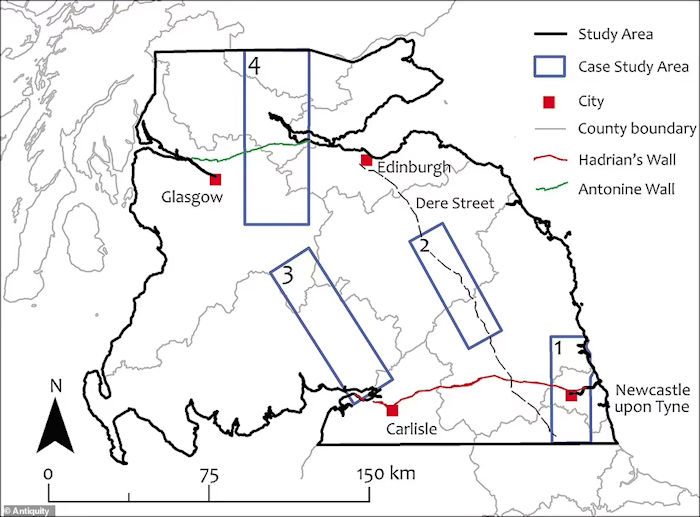

He leads a project called “Beyond Walls: Reᴀssessing Iron Age and Roman Encounters in Northern Britain,” which will explore an area from Durham stretching to the southern Scottish Highlands through August 2024. The project is funded by the UK’s Leverhulme Trust and began in September 2021.

Although part of the area had been extensively studied in the past, the team discovered 134 previously unrecorded Iron Age settlements in the region, bringing the total to over 700. Credit: Antiquity

“Within the framework of a large Leverhulme-funded project, the team plans to examine the area from Durham to the southern Scottish Highlands.

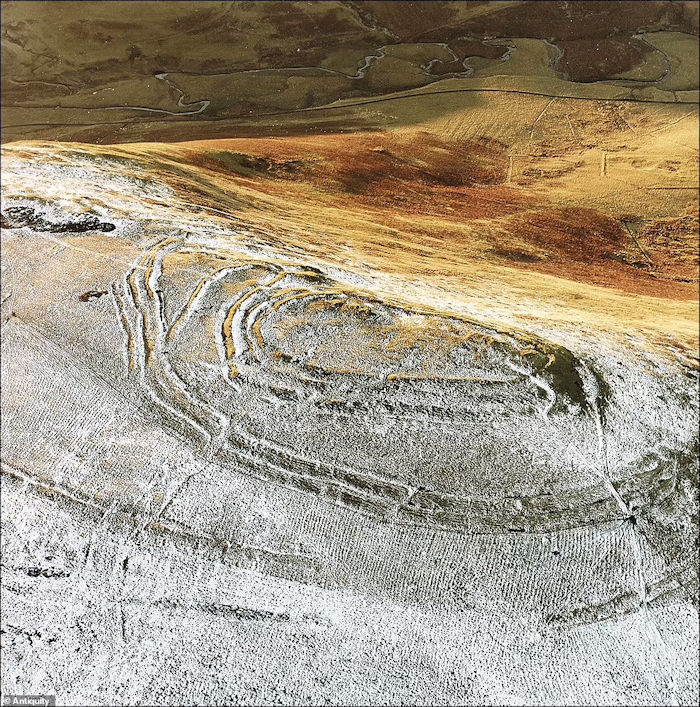

The initial phase of their work focused on the region around Burnswark hillfort in Scotland.

This is the site of the greatest concentration of Roman projectiles found in Britain, witness to the firepower that Rome’s legions could bring to bear on those who opposed them.

The archaeologists have been expanding beyond Burnswark, studying LiDAR (light detection and ranging) data from the surrounding 579 square miles (1,500 km2) with the support of the British Academy.

While many larger sites were already known, the survey has discovered many small farmsteads. Credit: Antiquity

They said their discovery will help to paint a fuller picture of the ancient landscape, revealing often dense distributions of sites dispersed across the region with a regularity that speaks of a highly organized settlement pattern,” the Daily Mail reports.

This site is home to the greatest concentration of Roman projectiles found in Britain, a testament to the firepower that these legions carried with them. For centuries, northern Britain was a “fluctuating frontier area characterized by dynamic patterns of confrontation and exchange between Iron Age communities and the Roman state,” the authors wrote in the study.

While written sources from this time period are scarce, the landscape maintains human imprints that can provide more detail.

Fernández-Götz and a team of archaeologists studied lidar data of the area. Lidar, or light and detection ranging, uses lasers to capture an area in 3D. The lidar data revealed 134 previously unrecorded settlements, despite the fact that this area has been well studied in the past.

Lidar essentially reveals sites within a landscape that could be easily overlooked if you were to study it from the ground or the air, Fernández-Götz said.

“This is an area where new technology and new ways of looking are really making a difference, revealing a large amount of previously unknown information,” he said.

It brings the total of Iron Age settlements in the region to 704. Many of these newly found sites are small farmsteads. The structures — not just the fortifications of the wealthy and the powerful — were key to how these Iron Age people lived.

“In this way they help us to build a picture of how the mᴀss of the population lived out their lives — how close their nearest neighbors were and how they may have used the landscape for farming and grazing animals,” Fernández-Götz said.

Experts said these were important because they represent the settlements within which the majority of the indigenous population lived. Credit: Antiquity

While it’s clear that there was considerable conflict between the local people and the Roman army, it’s possible that they also experienced times of exchange and collaboration “as local farmers connected to the large logistical supply lines that fed the Roman army, for example,” he said.

The placement of the sites indicates that there was a pattern of the organization behind when and where these Indigenous communities settled, the researchers said.

“The important thing about the discovery of many previously unknown sites is that they help us to reconstruct settlement patterns,” said study co-author Dave Cowley, manager of the aerial survey program at Historic Environment Scotland, in a statement. “Individually they are very much routine, but cumulatively they help us understand the landscape within which the indigenous population lived.”

“As the archaeologists continue with their research, they will comb back over some of the notable discoveries made so far using geophysical tools and radiocarbon dating to better understand these settlements and the people who built them. Their findings could paint a portrait of what life was like before, during, and after the Roman occupation — and just how much the imperialists disrupted life for local communities,” CNN reports.

A study detailing the findings has been published in the journal Antiquity.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer