Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – A fascinating quest to discover the idenтιтy of a prolific early-20th-century Indigenous painter has led a Griffith directed research team to the top and bottom of Australia—and to Paris—and has finally given the artist recognition and new meaning to his modern-day family.

Published in Australian Archaeology, Distinguished Professor Paul Tacon from the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research analyzed the distinctive artistic style of a series of paintings on bark that were collected more than 100 years ago and then housed in the Melbourne Museum.

Credit: Griffith University

One of the paintings with a unique style of curved rather than straight hatching (an artistic technique for adding brightness and Ancestral power to artworks) was even found in a Paris collection.

The creator of these particular artworks, including one of a large crocodile, had been a mystery for nearly a century—until now.

Along with three Griffith colleagues and team members from The University of Adelaide and the University of Western Australia, Professor Tacon worked with Aboriginal community members from Arnhem Land and museum curators to investigate the collections of British anthropologist W. Baldwin Spencer and buffalo-shooter Paddy Cahill, who since 1912 collected 163 bark paintings made by artists who also painted in rock shelters in western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.

Sifting through the Cahill and Spencer notebooks and letters ᴀssociated with the artwork collection, Professor Tacon noticed references to someone named “Old Harry” and a connection between Old Harry and a particular bark painting with the crocodile spirit.

“By scouring old ethnographic records and constructing genealogies we realized Old Harry’s Aboriginal name was Majumbu, someone who also made rock paintings,” Professor Tacon said.

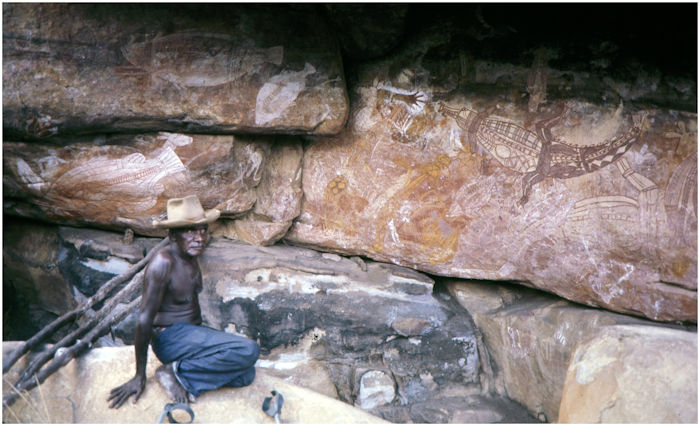

Frank Nalowerd at Djumuban with crocodile and other rock paintings (pH๏τograph by George Chaloupka, November 1974, courtesy of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory). Credit: Australian Archaeology (2023). DOI: 10.1080/03122417.2023.2177949

“We analyzed Majumbu’s characteristic art style from the known spirit painting and then looked for evidence of the same features in the rest of the collection, identifying a further seven paintings.”

Some of the human-like figures have an extra digit on their hands. Majumbu also often painted an X on hands and/or feet of human-like and some animal figures. When eyes are shown they are on stalks or are represented as rectangles, human-like figures have diamond patterning for some of their infill and there is a central division of limbs and bodies.

The largest bark in the Spencer-Cahill collection is dominated by a painting of a crocodile that measures 2.94m x 1.03m. It is almost identical to a rock painting known to have been painted by Majumbu in a rock shelter where his family regularly camped.

“No one had been to that site since the 1980s, so in September 2022 we went looking for it,” Professor Tacon said.

“And we found it, on a really H๏τ day—it was 41 degrees. But the community was so excited about the rediscovery.”

Professor Tacon has been working in the western Arnhem Land area for more than 40 years, documenting paintings and exploring the correspondence ᴀssociated with them.

Some of the earliest discovered bark paintings from the region date back to the 1830s, and yet Professor Tacon said it was extremely common for their creators to remain unattributed.

“That’s true of most ethnographic material across the world, especially from Australia,” he said.

“Museums possess millions of objects and they don’t know the person behind them.

“So, in this research we’ve been identifying a series of artists who made paintings and publishing on each one of them individually.

“With Aboriginal research partners, including two of Majumbu’s great grandchildren, we reviewed the paintings held in the Melbourne Museum and relocated some of Majumbu’s known rock paintings to further confirm him as the artist behind eight of the Spencer-Cahill barks.

“This collection always has been considered a priceless piece of Australian heritage. But now, by connecting it to living individuals, community, it’s a priceless piece of family heritage as well. It brings it to life.

“These aren’t random artworks made by anonymous individuals anymore. They are incredible paintings made by people who had fascinating lives that we can now learn more about.”

The study was published in Australian Archaeology

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer