Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com – When Cato was a child, one could see he would be different one day. He was extremely stubborn and could not tolerate obvious signs of injustice.

He was only 13 years old when he questioned the Roman general and dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla’s harsh methods and violations of laws and regulations.

Once he became aware of how Sulla seized power by force in the year 82 BC and proclaimed himself dictator, Cato asked his teacher why no one had killed the brutal Roman general yet.

According to the Greek philosopher, biographer, and essayist, Plutarch, the teenager Cato whispered to his teacher Sarpedon: “Why does nobody kill this man?” “Because,” said he, “they fear him, child, more than they hate him.” “Why, then,” replied Cato, “did you not give me a sword, that I might stab him, and free my country from this slavery?” Sarpedon hearing this, and at the same time seeing his countenance swelling with anger and determination, took care thenceforward to watch him strictly, lest he should hazard any desperate attempt. ” 1

At the time, one could already see Cato was going to be a determined man with enormous willpower.

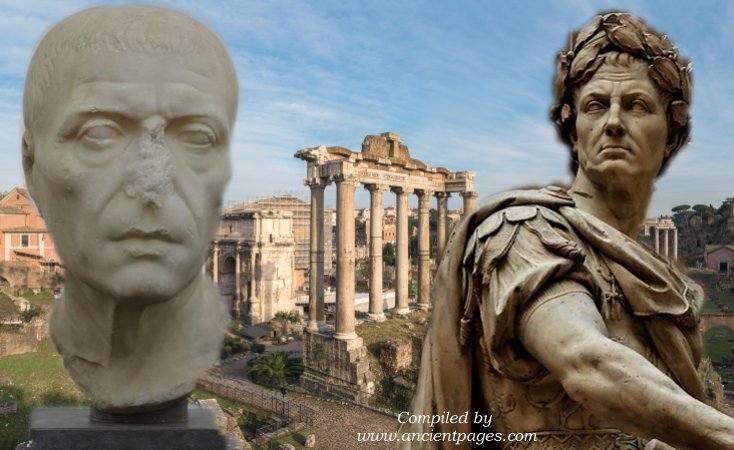

Born in 95 BC in Utica, Africa (now in Tunisia), Marcus Porcius Cato, also known as Cato of Utica or Cato the Younger, was a very conservative Roman senator. He struggled to preserve the Roman Republic against power seekers like Julius Caesar, whom he hated more than anything.

Maybe it was his unusual personality or the fact that he was immune to bribes and fought to uphold Roman traditions that contributed to later authors’ glorifying accounts of his reign. To many, Cato the Younger represented a model of virtue.

In time, Cato the Younger showed he was suitable for becoming a man of great political importance.

Cato’s grandfather Cato The Elder (234 BC – 149 BC), was famous for his conservative and anti-Hellenic policies. On numerous occasions, Cato the Younger demonstrated his strong will to maintain the old Roman traditions.

In 78 BC, when Sulla died, Romans wanted to wipe out the memory of his dictatorship. City officials wanted to remove a pillar that stood in the way in the large ᴀssembly hall Basilica Porcia, but Cato, who was 18 years, showed up and protested. Defending the pillar erected by his grandfather Cato the Elder, Cato argued the structure had stood there for hundred years, and there was absolutely no reason to change it.

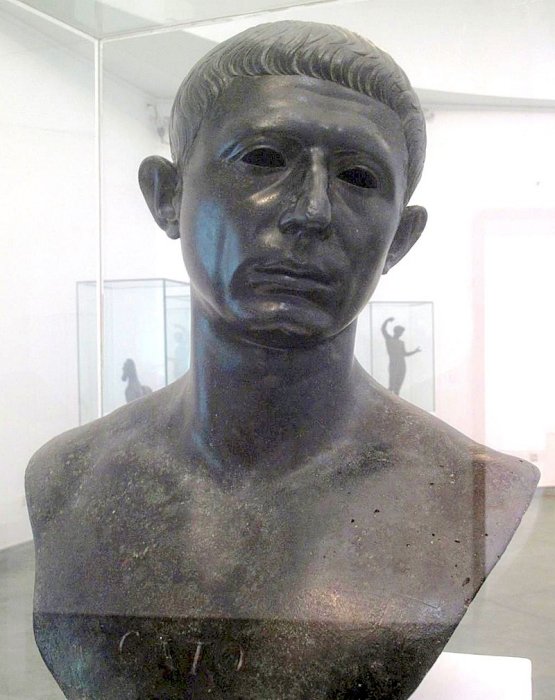

Bronze bust of Cato the Younger from the Archaeological Museum of Rabat, Morocco. Found in the House of Venus, Volubilis. Credit: Prioryman – CC BY-SA 3.0

His speech made an impression, and it was decided not to remove the pillar.

Walking around with his long hair and unshaven face, some could easily mistake him for a cave dweller, but Cato didn’t bother with his appearance, and he was undoubtedly not vain.

Cato the Younger consciously ᴀsserted his old Roman virtue by wearing his toga without a tunic, and “he became accustomed to enduring heat and snow with his bare head and to moving on foot without a vehicle,” writes the historian Plutarch.

Cato The Younger Was An Honest Leader In A Corrupt Age

Cato the Younger’s political career started in 65 BC, a turbulent period in the history of ancient Rome.

The Roman population was divided. The underclass had become poorer, with even more debt and many populists demanded radical social and political changes.

Cato the Younger had just returned to Rome after finishing his military commission in Macedon and a personal journey in the Middle East.

At 28, Cato the Younger was elected as quaestor, a position that provided him with knowledge of the Roman tax code. Cato soon discovered that former men in the post office had made a lot of money by accepting bribes to erase some debts, which was unacceptable to him.

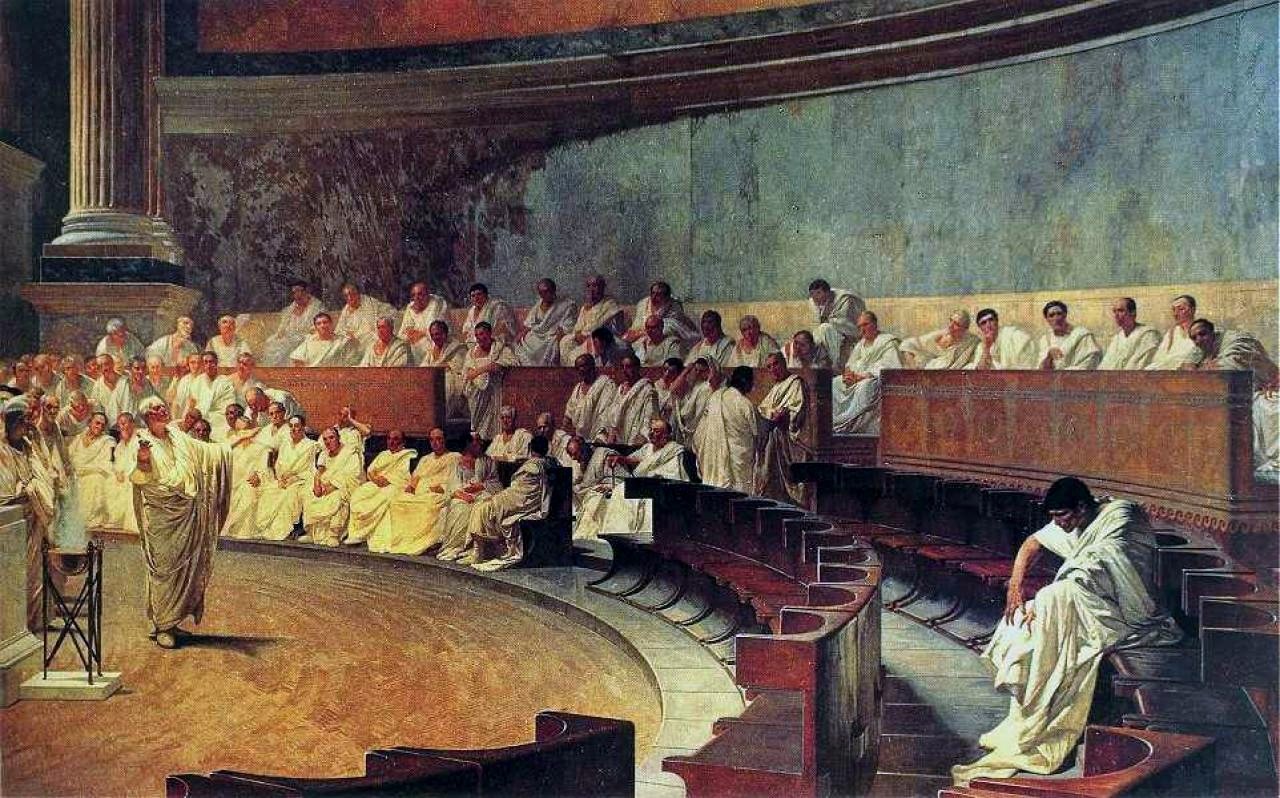

Representation of a sitting of the Roman senate: Cicero attacks Catiline, from a 19th-century fresco in Palazzo Madama, Rome, house of the Italian Senate. Credits: Public Domain – Read more: Ancient Roman Government Structure And The Twelve Tables

“Once elected quaestor, Cato, in his first act, stabbed straight at the heart of the bureaucracy. He summarily fired all clerks and ᴀssistants whom he judged unfit for office or guilty of corruption. It was the kind of wholesale housecleaning that made headlines – and drew out the long knives of the career of clerks. Who did this young man think he was? What didn’t he understand about the compact between the elected and the appointed? This sort of thing was especially appalling from a son of the establishment that had so benefited from the energies and exertions of the bureaucracy.

Cato, though, was oblivious to any backlash. What was there to know besides the fact that the law had been broken? Still, as with his military command, he matched strictness with softness when appropriate. In the course of his audit, he found that a number of clerks had erred not willfully but out of ignorance of the law. These, he tutored in the rules and responsibility of the treasury. If they were willing to accept his tutelage, he was ready to keep them at their jobs. If not, they would be shown a swift exit. ” 2

Cato’s And Caesar’s Rivalry Begins In The Senate

Cato’s righteousness attracted attention, and in 63 BC, he was elected to the people’s tribune. In the Roman Senate, Cato the Younger met Julius Caesar, whom he despised. Looking through the eyes of Cato, Julius Caesar must have been a bit of a clown. Cato the Younger followed the principles of Stoicism and was moderated in every aspect of his life. He adopted an ascetic lifestyle with strict exercise, consumed only necessary food, and drank the cheapest wine on the market. He was a private man, and parties were not on his agenda.

Statue of Julius Caesar in Rome. Credit: Adobe Stock – james_pintar

To a man like Cato the Younger, the extravagance of Julius Caesar must have been appalling, and there was no lack of disagreements between these two.

Cato the Younger was naturally very annoyed when Julius Ceasar was elected one of Rome’s two consuls in 59 BC. It was the republic’s most influential post. And Cato warned people were paving the way for a tyrant, but few listened.

Cato’s opposition to Pompey, Caesar, and Marcus Licinius Crᴀssus helped bring about their coalition in the so-called First Triumvirate that was broken in 54 BC, simultaneously with Cato’s election as praetor.

Cato the Younger attempted to obtain a consulship in 51 B.C. Roman consuls usually seized power through intimidation, bribery, and show business. Cato the Younger did no such thing, which is most likely why he failed to become a consul.

Cato The Younger Committed Heroic Stoic Suicide

Julius Caesar gathered his XIII Legion and declared war on Rome. While Caesar attacked and defeated his former ally, Pompey, Cato fled to Utica, but he understood this was the beginning of the end.

In April 46 BC, news came that former consul Metellus Scipio and his army that defended Utica had fallen. Cato encouraged the few Romans in Utica to defend the city, but they soon realized they had no chance against Julius Caesar’s army and asked to leave the doomed city. Their wish was granted.

When Cato’s son asked him to give up, he refused: “I, who grew up in freedom with the right to speak freely, can not change in the autumn of age and learn to be a slave,” he explained, according to the author Dio Cᴀssius.

The same night, Cato the Younger took his sword and stabbed himself in the stomach, but he didn’t die at once. When his relatives found him, they called for a doctor who sтιтched together the wound. As soon as Cato regained consciousness, he tore up the wound again with his last strength and died.

Cato ending his life became “the solemnly revered and much-imitated model of the heroic Stoic suicide.

It was how the younger Cato chose to stage his end and how others celebrated it. It explains why political opponents of the Emperors, who were ordered to kill themselves or even were executed, came to the thought of, and probably thought of themselves, as following the great Stoic Cato in death. 3

When Julius Cesar heard the news, he shouted: “Cato, I grudge you your death, as you would have grudged me the preservation of your life.

Two years later, Julius Caesar was ᴀssᴀssinated.

Written by Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Updated on December 7, 2022

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

- Plutarch – Cato the Younger

- Rob Goodman – Rome’s Last Citizen: The Life and Legacy of Cato, Mortal Enemy of Caesar

- Griffin, Miriam. “Philosophy, Cato, and Roman Suicide: II.” Greece & Rome33, no. 2 (1986): 192-202.

- Gordon, Hattie L. “The Eternal Triangle, First Century B.C.” The Classical Journal 28, no. 8 (1933): 574-78.