Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Long considered impossible to decipher, we can now finally learn the truth about the mysterious code found hidden in an old silk dress in Maine, USA.

The intriguing story started when Sara Rivers Cofield spotted a silk dress in an antique mall in Maine. Being an archaeologist who also also collects old dresses and handbags for fun she decided to buy the dress that had caught her eye. Once she took it home found a secret pocket hidden under that bustle, inside the seams of the skirt. Upon further inspection, she also found crumpled bits of paper inside the secret pocket.

This is the 1880s silk bustle dress in which crumpled bits of paper containing a code were found. The pocket where the code was found is located under the overskirt at the right hip. Credit: Sara Rivers Cofield

She recognized that both the dress and the paper were likely from the 1880s. What she couldn’t decipher was the meaning of messages written on the paper – lines of text, many beginning with a place name, followed by seemingly random verbs and nouns.

Bismark, omit, leafage, buck, bank

Calgary, Cuba, unguard, confute, duck, fagan

Spring, wilderness, lining, one, reading, novice.

What was the meaning of this message? Someone was obviously trying to say something, but what?

Curious to learn more, Rivers Cofield posted about the dress and its unusual message on her blog in 2014.

On her blog she wrote: “The […] discovery arose when I turned the skirt inside out; there was a pocket! Okay, neat, but not earth shattering. Lots of 19th-century dresses had pockets. But then things got weird. I mean usually built-in pockets don’t play hard-to-get, but even with help from my perennial antiquing partner, my mom, it took a while to get to the thing.

Instead of being easily accessed through an inconspicuous slit in the over-skirt, this pocket opening is completely concealed by the over-skirt; as in, you have to hike up the draped silk, expose the cotton under-skirt, and generally disrupt the whole look to get at the pocket. Also, thanks to some tacked areas sewn into the skirt to make it drape properly, it wouldn’t have been possible to get at the pocket at all without causing a rip if someone had the dress on. We had to do some seriously careful maneuvering to get at it.”

News about the code spread, and the story gained attention. Several experts tried to decipher the message but to no avail. The silk dress cryptogram became considered among the 50 most “unsolvable” codes in the world.

Codes are meant to be broken, and Wayne Chan, a research computer analyst at the University of Manitoba in Canada, managed to decipher the silk dress message!

Chan was able to determine the words used in the message were intended to transmit local weather via telegraph. To make a long story short, the silk dress code was a weather report!

In the mid 1800s people relied on the telegraph to send and receive news quickly.

In the United States, a series of long or short taps made by a person on one end of the wire were recorded by an operator on the other end as dots and dashes. This meant messages could be tapped into a machine in one town and heard and recorded in another town hundreds of miles away in just a matter of minutes.

To keep wired messaging via telegraph inexpensive, a sort of shorthand was developed.

“Since telegraph companies charged by the number of words in a telegram, codes to compress a message to reduce the number of words became popular,” Chan wrote in his science paper published in the journal Cryptologia.

To decipher the message, Chan studied about 170 telegraphic codebooks, but none of them could provide him with the information he sought. Then, he came across an old book called “Telegraphic Tales and Telegraphic History” which contained a section about the weather code used by the U.S. Army Signal Corps. The examples in the book seemed to look similar to the codewords from the dress, leading him to believe that the code was related to weather.

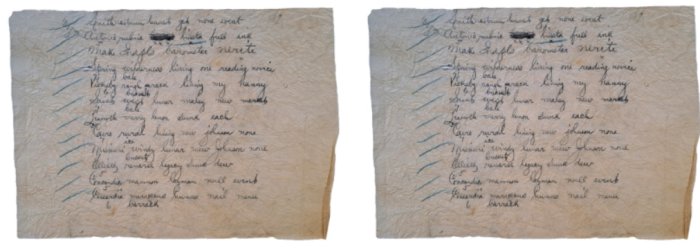

The code sheets were found in the hidden pocket of an 1880s silk bustle dress. Credit: Sara Rivers Cofield

The invention of the telegraph had transformed many things, including weather forecasting. For the first time in history, news about the weather could travel faster than the weather itself, Chan explains. However, weather observations, consisting of a number of meteorological variables, had to be condensed, just like other telegraph messages, to save money. Code books were published for the weather observers to use. So it seemed likely that the book he would need to translate the code from that dress was one used by the Army Signal Service Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce in the 1870 to 1891offsite link, a bureau that would eventually become NOAA’s National Weather Service.

There were some excerpts of such books online. But Chan knew he needed the entire book if he really wanted to decode all of the messages conclusively.

Many hours of dedicated sleuthing and academic research brought him to Katie Poser, the librarian at NOAA’s Central Library in Silver Spring, MD, who was able to provide a PDF copy of a weather telegraph code book, published in 1892. It wasn’t the exact book Chan needed, but it did help him realize he was on the right track.

Using the NOAA resource that Poser sent to him and some other resources, Chan deduced that the messages were from Signal Service weather stations in the U.S. and Canada.

According to NOAA’s press statement, each line written on the papers indicated weather observations at a given location and time of day, which was telegraphed into a central Signal Service office in Washington, DC.

The format of weather messages at the time were as follows:

Each started with the station location, which was unencoded, followed by codewords for temperature/pressure, dew point, precipitation/wind direction, cloud observations, and wind velocity/sunset observations.

So for example,

Bismark, omit, leafage, buck, bank

Was code for:

BISMARK Station name: Bismarck, Dakota Territory (in present-day North Dakota)

OMIT Air temperature: 56 F Barometric pressure: 0.08 in Hg (Note that only the fractional part of the pressure value was telegraphed, unless the station was west of the 97th meridian or the pressure was below 29.4 in Hg or above 30.38 in Hg). In this case, the actual reading was 30.08 in Hg)

LEAFAGE Dew point: 32°F Observation time: 10:00 p.m.

BUCK State of weather: Clear Precipitation: None Wind direction: North

BANK Current wind velocity: 12 mph Sunset: Clear

Code cracked! Mystery solved!

Further research using old daily Signal Service weather maps provided from the NOAA Central Library also allowed him to deduce that those observations were taken on May 27, 1888.

What remains unknown is who owned the dress or why she had weather codes stuffed in a hard-to-access pocket near her petticoats one spring day. We know that hundreds of men and women were volunteer weather observers for the Smithsonian in the 1800s. But they mailed in their weather observations via the U.S. Postal Service, and would not have used telegraph codes.

Rivers Cofield also notes that the dress – although beautiful and fancy to our modern eyes – was not exactly what someone would wear to a ball. It was more like the ‘business casual’ of the day, and to her, that does indicate it might have been worn to work.

The study was published in the journal Cryptologia.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer