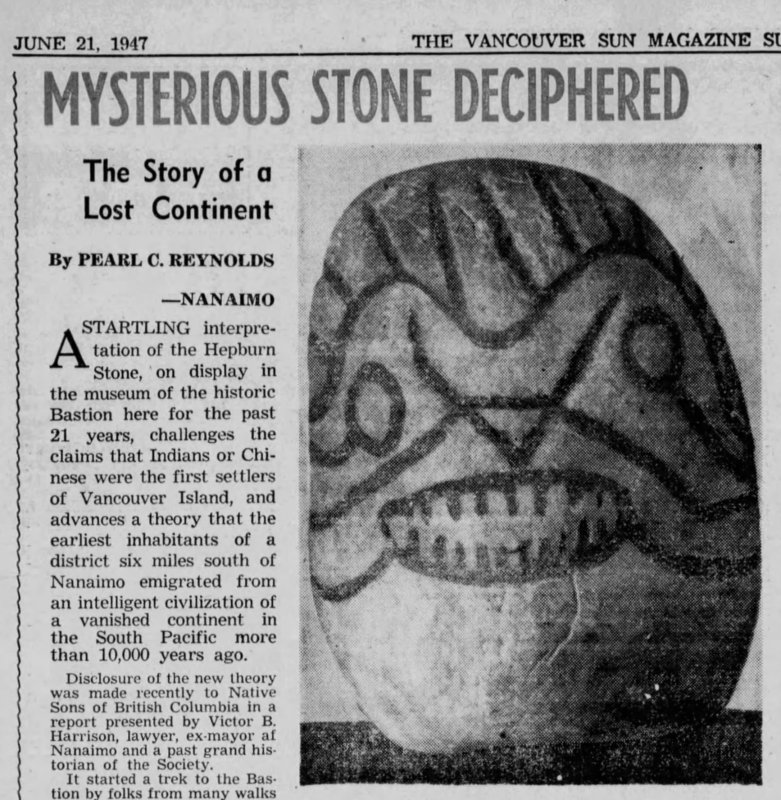

Shanon Sinn – AncientPages.com – Vancouver Island’s enigmatic Hepburn Stone is displayed at the Nanaimo Museum. At first glance, it is nothing more than a large rock under glᴀss. On closer inspection, there is a rough carving on its surface depicting a face.

J.T. Hepburn dug the stone up near the mouth of the Nanaimo River in the 1920s. The Province reported that the 100-pound rock had been found while Hepburn was digging a well. He had found the stone 14 feet underground, embedded in the roots of a thousand-year-old tree stump. The paper estimated it could be 2000 years old.

The carved rock was said to depict either a fearsome face or a spirit. The artistry resembled nearby Snuneymuxw First Nations sandstone petroglyphs, but the lines were in hard-to-work granite and the canvᴀss was three-dimensional.

The Hepburn Stone. Credit & Copyright: Shanon Sinn

Hepburn presented the stone to Nanaimo’s Native Sons (a pioneer fraternal order) in 1926—which was when the story appeared in the Province. The Native Sons would preserve the relic inside Nanaimo’s Bastion Museum. Later articles would claim the stone had been discovered a year or two earlier, either in 1923 or 1925. It would come to be known as the Hepburn Stone.

Sometime between September 1939 and May 1940, two British scientists spent a week studying the artifact and the location it had been found at. By counting the tree stump’s rings, they were able to determine the tree had been 640 years old when it was cut down. The stone’s actual weight was found to be 86 lbs. and 10 oz.

Depending on what source you choose to believe, the scientists found the stone’s real depth to be either 22 or 28 feet beneath the surface. Using this measurement, they calculated the relic’s age to be 15,000-years-old—not the 1,500 years that had become popular. The reduction of the tree’s age lent credibility to the scientific process used, as the data didn’t all shift in favour of an older artifact.

Credit: Public Domain

A museum star should have been born. But this was the era of sensational newsmen, tourism promotion, and foreign made Indigenous art products. The Native Sons of Nanaimo, in particular—who the stone had been given to—were a Eurocentric heritage cult. While they worked to preserve historic sites, totem poles, and petroglyphs, they also promoted a romantic image of pioneers triumphing over Indigenous nations and peтιтioned the government to not allow Asians to vote.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Indigenous people on the West Coast were being sentenced to jail for conducting traditional ceremonies, even as unfaithful depictions of their totem poles were being used for tourism. Children were taken from their homes and sent to residential schools to learn about their people through a colonial lens instead of from their own families. Indigenous cultures were being dismantled and reimagined. It was popular to speak of their people as disappearing.

A 15,000-years-old Hepburn Stone meant it could only fall into one of two categories: it was either an incredibly ancient Indigenous artifact, or it was proof of a lost civilization pedating them. The second category had greater appeal, as the stone was older than the scientifically agreed upon date of human arrival. The “lost race” narrative also meant Indigenous people had once been immigrants and colonizers themselves, which would weaken their legal land right claims and lessen any existing settler guilt of colonization.

B. A. McKelvie was a high member of the Native Sons, editor for the British Colonist, and writer for the Province. He was especially eager to promote the lost race theory. Between 1935 and 1955, McKelvie gave multiple speeches, wrote articles, and published two books referencing the Hepburn Stone. It wasn’t the only artifact he offered as proof of a lost race, but he used it often, as it was an item that had been scientifically dated. Other prominent members of Nanaimo’s Native Sons also promoted this theory, including former mayor Victor B. Harrison and the museum’s longtime director Joseph Muir.

The wildest story of the Hepburn Stone’s origin claimed it had been created by survivors of a destroyed island kingdom called Mu, sometimes Mee. This densely populated island had once been located south of Hawaii, but was obliterated by a cataclysmic earthquake, a volcano, and raging fire. The stone’s face somehow explained all of this in specific detail; including the displeasure of the gods and the refugees’ belief they were descendants of deer.

For those who did not embrace the Kingdom of Mee theory, the lost race was Jewish, Chinese, Welsh, or Middle Eastern. According to one claim, translated Chinese archive documents revealed that Buddhists from Kipin (modern day Afghanistan) had been to America. The lines at the top of the Hepburn Stone were said to be, “strongly Egyptian or Arabian in design” and the petroglyphs were theorized to be Egyptian. Traces of Italian, Jewish, and “Hinduistani” languages could also be found in local Indigenous languages.

Other Indigenous artifacts were discovered in the area and some of these were used to promote the lost race theory, as well. The Native Sons claimed an ancient samurai sword had been found in Nanaimo during roadwork and that a string of old Chinese coins had been discovered. How the discoveries of relatively modern items were connected to a 15,000-year-old piece of art was never explained.

Like other fraternal orders, the Native Sons held initiation ceremonies and other secret rites. The Hepburn Stone became a sideshow cult curio as it faded more and more into the background as a serious historic find.

Snuneymuxw First Nation tried to convince people the petroglyphs were sacred to them—that they were not, in fact, evidence of a lost race. It looked unlikely that anyone would recognize the much older Hepburn Stone as an ancient Snuneymuxw artifact—even though their oral history claimed they had been in the Nanaimo River area “since time immemorial.”

Nanaimo Museum currently displays the Hepburn Stone with a caption stating it is at least 700 years old. This acknowledges the tree ring counting as evidence of the stone’s great age, but it does not take into account the depth the stone was found at. The conservative estimate distances the museum from their fraternal predecessors.

Vancouver Island is known worldwide for its arresting natural beauty, but those who live here know that it is also imbued with a palpable supernatural energy. Researcher Shanon Sinn found his curiosity piqued by stories of mysterious sightings on the island―ghosts, sasquatches, sea serpents―but he was disappointed in the sensational and sometimes disrespectful way they were being retold or revised. Acting on his desire to transform these stories from unsubstantiated gossip to thoroughly researched accounts, Sinn uncovered fascinating details, identified historical inconsistencies, and now retells these encounters as accurately as possible.

Investigating 25 spellbinding tales that wind their way from the south end of the island to the north, Sinn explored hauntings in cities, in the forest, and on isolated logging roads. In addition to visiting castles, inns, and cemeteries, he followed the trail of spirits glimpsed on mountaintops, beaches, and water, and visited Heriot Bay Inn on Quadra Island and the Schooner Restaurant in Tofino to personally scrutinize reports of hauntings. Featuring First Nations stories from each of the three Indigenous groups who call Vancouver Island home―the Coast Salish, the Nuu-chah-nulth, and the Kwakwaka’wakw―the book includes an interview with Hereditary Chief James Swan of Ahousaht. Read more

Over the last few years, new discoveries have raised questions about the Hepburn Stone’s real age. Human occupation in the Americas is now thought to have happened at least 16,000 years ago, suggesting nautical arrival over land bridge theories.

Researchers at the Bluefish Caves in the Yukon have carbon dated human presence from 24,000 years ago. Mexico’s Chiquihuite Cave researchers have dated 25,000-year-old human occupation, as well. Perhaps most significant, two Heiltsuk sites near Vancouver Island have been carbon dated at 13,000 and 14,000 years old.

Could the Hepburn Stone be a 15,000-year-old Indigenous artifact? It is possible. Anthropologists would need to understand more about stone working techniques from Indigenous antiquity to say for certain, but the Hepburn Stone could be far older than academic historians recently believed. Even if the 1940s scientists had been off in their calculations, the artifact is likely still thousands of years old.

The Hepburn Stone could be proof of what Snuneymuxw Nation had been saying all along. That they have been on Vancouver Island since time immemorial.

Updated on January 24, 2024

Written by Shanon Sinn – AncientPages.com

Shanon Sinn – Author of The Haunting of Vancouver Island (BC and Amazon Bestseller). Published in the Times Colonist, Nelson’s Canadian Corrections textbook, Folklore Thursday, and elsewhere. For a full bio please visit here.

Copyright © Shanon Sinn – AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of Shanon Sinn and AncientPages.com