The two prospectors were looking for gold, and a sH๏τ of dynamite seemed like a good start.

It was summer 1934 in Central Wyoming. Cecil Main and Frank Carr set a charge in a gulch at the foot of a high point in the Pedro Mountains that strip down the east side of the Pathfinder Reservoir.

The explosion ripped open the earth and revealed a cave. Main crawled into the cave — a small place, almost a coat closet tipped over. There he found a rock ledge, about two and a half feet above the ground. No gold. The cave was empty.

Except for the mummy.

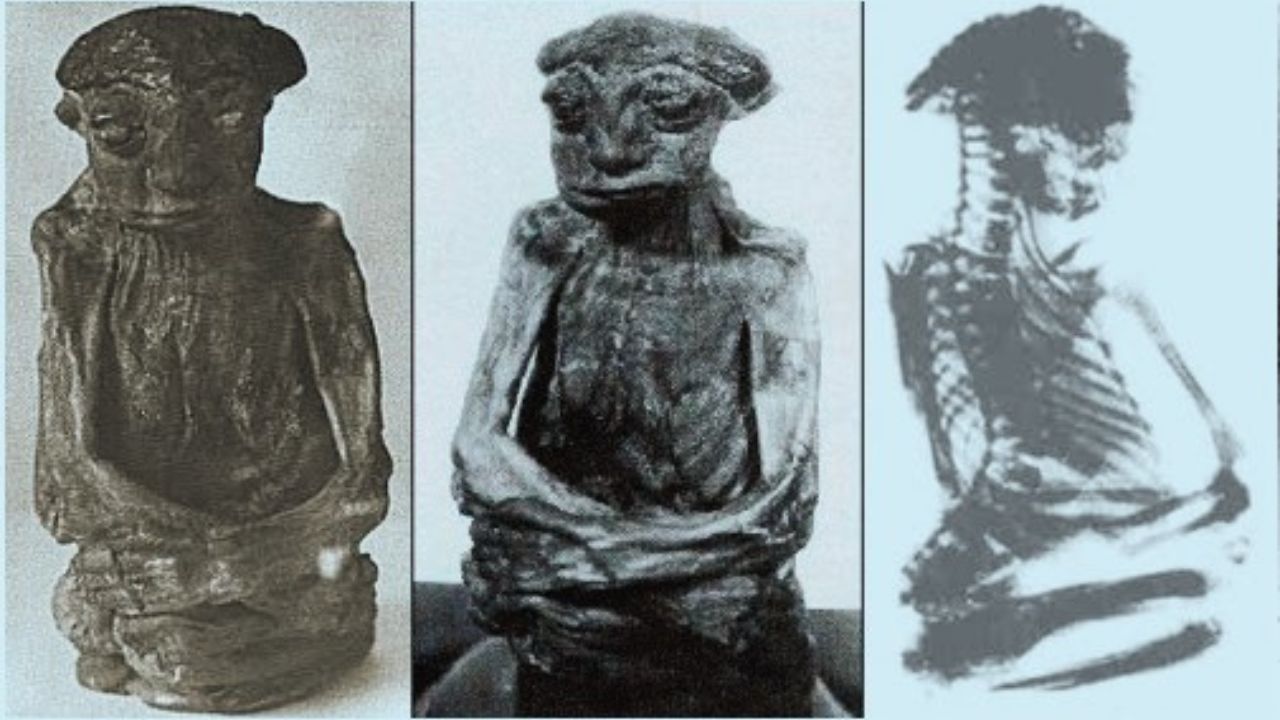

It looked like a small wizened man sitting on the ledge — his eyes closed, arms crossed, his feet tucked under him. His skin was brown and dried by the arid Wyoming climate. His mouth was drawn into a placid scowl — a lean Buddha with a misshapen head.

It was tiny, perhaps six-and-a-half inches tall or so sitting down. It weighed just about a pound. Main and Carr may not have known it at the time, but they held a treasure in their hands.

The Pedro Mountain Mummy made the rounds. Two years later, a sworn statement by Main shows the mummy belonged to a Homer F. Sherrill. At some point, it was owned by Floyd Jones, who had a drug store in the Wyoming town of Meeteetse. A young basketball player who visited the town at the time later recalled seeing the mummy in the drug store window. Jones sold postcards of the mummy to bring in some additional cash. It was a sideshow attraction.

In 1936, a young Eugene Bashor convinced his father to pay the 25-cent cost for his son to see the mummy. That rushed look at the mummy was

the start of Bashor’s lifelong search for more information about it.

But the mummy tale was far from over. Eventually it made its way to Ivan Goodman, a car dealer in Casper — not far from where the mummy was discovered. He showed off the mummy, by now seated atop a wooden base topped by a tall inverted glᴀss jar — almost as if the mummy was a cake on display. At some point, the mummy got x-rayed. The images proved the mummy wasn’t a fake — its flesh stretched over a skeleton, with visible vertebrae, rib cage, and arm and leg bones.

Goodman featured the mummy in car advertisements, and apparently offered for display by others. A hype poster barked the claims: “It’s Educational! It’s Scientific! It will amaze and thrill you. It’s a pygmy preserved as it actually lived!” The poster featured pH๏τos of the mummy and the x-rays of it, from the left and right. Goodman’s name was at the end of the tale, with a blank line to be filled in by whoever was displaying the mummy. This pygmy was 65 years old when it died, the poster claimed. That wasn’t true. But it was a fascinating story — one that could sell.

Also, one that could be stolen. The mummy was lost about 1950. It’s not clear how, and press reports vary. Some claim Goodman took the mummy to New York City and lost it to a con man. Others say he sold it. Others say the mummy just vanished. Years later, University of Wyoming physical anthropologist George Gill picked up on the story, reportedly from his students. He says it’s likely the mummy was an infant suffering from anencephaly — a defect that means a fetus doesn’t develop major portions of the brain.

The mummy wasn’t a pygmy. It wasn’t an old man. It was an infant born with a birth defect almost always fatal. Unusually, it was buried in a cave in a seated position atop a ledge. The mummy also sparked thoughts of the legend of “little people,” tales of a race of tiny human beings described in Indian legends in Wyoming and elsewhere. It’s possible buried mummies such as the Pedro Mountain Mummy might have started and sustained such legends.

In 2005, John Adolfi of Syracuse, New York, offered a $10,000 reward for the mummy, claiming it would disprove evolution.

Yet the mummy stayed hidden.

Since Gill first heard of the Pedro Mountain Mummy, he’s served as something of a living archive for its news and knowledge. Someone once brought him what they thought was a valuable mummy head. Gill’s research showed it was just an interestingly carved and dried hunk of vegetable matter. He stores that in cotton, tucked into a clear globe. Gill thought the Pedro Mountain Mummy was gone. But he says he’s recently learned the mummy may be okay, somewhere safe. But he won’t say more.