Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com – On October 31, many of us celebrate Halloween, a tradition that is thought to have originated with the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain.

What is the connection between Halloween and Samhain? Credit: Public Domain

What is the connection between Halloween and Samhain? Credit: Public Domain

It is a time of celebration and supersтιтion. We see carved, decorated pumpkins on the streets, people of all ages wearing scary costumes, and children wandering the neighborhood knocking on doors demanding treats.

Seeing through the eyes of an outsider unfamiliar with the tradition and history behind Halloween, this behavior can appear rather peculiar. So, how did it all start? What is the true meaning of Halloween, and why is the celebration ᴀssociated with a 2,000-year-old ancient pre-Christian festival?

This article examines the facts and history of Halloween – also called All Hallows’ Eve.

Samhain: An Ancient Celtic Festival

Most historians agree that Halloween dates back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, celebrated 2,000 years ago in the area that is now Ireland, the United Kingdom, and northern France.

Credit: Public Domain

It was a time when people living there celebrated their New Year on November 1 Samhain (pronounced “sah-win”), which means “summer’s end” in Gaelic, and this was a day that marked the end of summer and the harvest and the beginning of the dark, cold winter.

The worlds between death and the living became blurred. To ancient Celts, this was when ghosts of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ returned to earth.

The ghosts of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ were believed to damage crops and to combat the threat, ancient Celts often held raging bonfires – a fire was used as a common way to ward off evil spirits.

The practice continued throughout the region even after Christianity took hold in the Middle Ages, and the festival was renamed All Hallows’ Eve. Later, the fires shrank in towns and were instead placed within turnips or gourds, which were inexpensive, readily available, and safe “containers.”

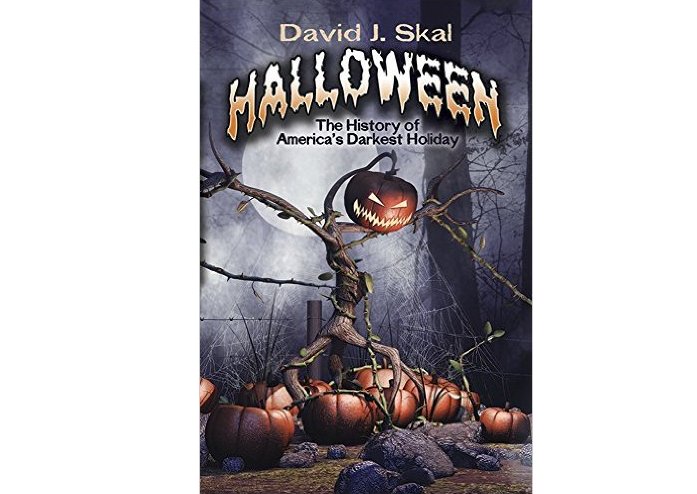

Acclaimed cultural critic David J. Skal explores one of America’s most perplexingly popular holidays in this original mix of personal anecdotes and social analysis. Skal traces Halloween’s evolution from its dark Celtic history and quaint, small-scale celebrations to its emergence as mammoth seasonal marketing event.

Skal takes readers on a cross-country survey that covers remarkably divergent perspectives, from the merchants who welcome a money-making opportunity that’s second only to Christmas to fundamentalists who decry Halloween a form of blasphemy and practicing witches who embrace it as a holy day. He also profiles individuals who revel in this once-a-year occasion to participate in elaborate fantasies. Their narratives, combined with the author’s cultural analysis, offer a revealing look at an intriguing aspect of our national psyche. Read more

“Originally, they were simply pierced to emit light and were carried to scare away the spirits from the Otherworld who could enter the mortal realm,” said Verlyn Flieger, a mythology specialist at the University of Maryland. Carving the gourds became common over time, Flieger explained. “Designed to ward off scary faces, they gradually took on the aspects of the very foes they were supposed to forestall,” she said.

Halloween And All Souls Day

By 43 A.D., the Roman Empire had conquered most of Celtic territory. During the four hundred years they ruled the Celtic lands, two festivals of Roman origin were combined with the traditional Celtic celebration of Samhain. The first was Feralia, a day in late October when the Romans traditionally commemorated the pᴀssing of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. The second was a day to honor Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees.

The symbol of Pomona is the apple, and incorporating this celebration into Samhain probably explains the tradition of “bobbing” for apples practiced today on Halloween.

Acclaimed cultural critic David J. Skal explores one of America’s most perplexingly popular holidays in this original mix of personal anecdotes and social analysis. Skal traces Halloween’s evolution from its dark Celtic history and quaint, small-scale celebrations to its emergence as a mammoth seasonal marketing event.

All Souls Day – Credit: Adobe Stock – Caroline

Skal takes readers on a cross-country survey that covers remarkably divergent perspectives, from the merchants who welcome a money-making opportunity that’s second only to Christmas to fundamentalists who decry Halloween a form of blasphemy and practicing witches who embrace it as a holy day. He also profiles individuals who revel in this once-a-year occasion to participate in elaborate fantasies. Their narratives, combined with the author’s cultural analysis, offer a revealing look at an intriguing aspect of our national psyche. Read more

On May 13, 609 A.D., Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome in honor of all Christian martyrs, and the Catholic feast of All Martyrs Day was established in the Western church. Pope Gregory III (731–741) expanded the festival to include all saints and martyrs and moved the observance from May 13 to November 1.

By the 9th century, the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it gradually blended with and supplanted the older Celtic rites. In 1000 A.D., the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day to honor the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. It is widely believed that the church attempted to replace the Celtic festival of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ with a related but church-sanctioned holiday.

All Souls Day was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades, and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels, and devils. The All Saints Day celebration was called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmesse, meaning All Saints’ Day).

The night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-Hallows Eve and, eventually, Halloween.

Pumpkins Replaced Turnips

When Irish immigrants and descendants of the Celts came to America in the 1800s, they brought the tradition of Samhain. They soon noticed there were not enough turnips in America, so instead, the settlers started using pumpkins. Soon, a new tradition was born, and people began carving out faces and placing candles in pumpkins.

The pumpkins had a special meaning to the Irish, who believed that a ᴅᴇᴀᴅ headless man could rise from the grave, chop the heads of the living, and put it on himself.

Credit: Public Domain

Therefore, the Irish placed a pumpkin with a candle on the graves to scare away the headless man.

American Halloween Tradition Of “Trick-Or-Treating”

According to folklorist John Santino, “The tradition of dressing in costumes and trick-or-treating may go back to the practice of “mumming” and “guising,” in which people would disguise themselves and go door-to-door, asking for food. Early costumes were usually hidden, often woven out of straw, and sometimes, people wore costumes to perform in plays or skits.

The practice may also be related to the medieval custom of “souling” in Britain and Ireland, when poor people would knock on doors on Hallowmas (November 1), asking for food in exchange for prayers for the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ.

Trick-or-treating didn’t start in the United States until World War II, but American kids were known to go out on Thanksgiving and ask for food — a practice known as Thanksgiving begging.

Some Christians have expressed concern that Halloween is somehow satanic because of its roots in pagan rituals. Still, ancient Celts never worshipped a creature resembling the Christian devil, and they had no concept of it. The Samhain festival had long since vanished when the Catholic Church began persecuting witches in its search for satanic cabals.

Today, we celebrate Halloween, and the festival’s popularity has increased. It is now celebrated in more countries worldwide, but we often need to remember the meaning behind the festival.

Written by – Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Updated on Oct 30, 2023

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

References:

The Celtic Times