A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – In Babylonian mythology, Irkalla was the underworld from which there was no return. The realm of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ or the lower world was also called Arali, Kur, Kigal, and Gizal.

There were two traditions explaining how humans entered the netherworld. According to one, the road to the underworld pᴀssed through the steppe land swarming with demons, across the Khabur River, and then through seven heavily guarded gates.

Another version described a road to the netherworld crossed by boat down one of the rivers of the upper earth. Then, across the apsu (the sweet waters under the earth) to Irkalla, the lower earth.

At first, the only ruler of Irkalla was Ereshkigal (“Queen of the Great Below”), a granddaughter of Enlil and older sister of Inanna (Ishtar). Later she ruled the netherworld with her husband, Nergal, the king of death who brings disease, plague, and all misfortunes caused by heat. Ereshkigal’s judgment and laws were always indisputable.

Irkalla was the abode of many demons, including the hideous child-devourer Lamashtu, the fearsome wind demon and protector god Pazuzu, and great demons Gallas (or Gallu) busy with dragging mortals to Irkalla.

Location Of Irkalla

Based on various texts, it can be ᴀssumed that the Babylonians located the entrance to the underground world, where the sunset was in the western desert.

Left: Bronze statuette of Pazuzu (c. 800 – c. 700 BC). Credit: Public Domain – Right: Close-up of Lamashtu from a lead protection plaque dating to the Neo-ᴀssyrian Period (911 – 609 BC). Credit: Public Domain

The Babylonian sun god, Shamash, descended to these regions in the evening. Then, he appeared again from the mountains in the east in the morning. The netherworld was situated even lower than the Abzu, the fresh-water ocean beneath the earth.

Grave Of The Deceased – The Entrance To Irkalla

In Babylonian writings, the grave was the entrance to the underground world for the man who was buried in it. The Sumerian beliefs inspired the Babylonian myths, which were later repeated and further developed.

All people, regardless of their positions, age or morals, descended after death to Irkalla. It was the same afterlife for all souls.

The only food or drink was dry dust, but family members of the deceased would pour libations for them to drink.

In “The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood,” Irving Finkel cites a description of Irkalla as a dreary place: The netherworld was described as a dreary place:

To the gloomy house, seat of the netherworld,

To the house which none leaves who enters,

To the road whose journey has no return,

To the house whose entrants are bereft of light,

Where dust is their sustenance and clay their food.

They see no light but dwell in darkness,

They are clothed like birds in wings for garments,

And dust has gathered on the door and bolt…”

(The Descent of Ishtar to the Netherworld” 4-11)

Not all views of the afterlife were the same among ancient beliefs of other cultures.

Unlike other views of the afterlife, in the Sumerian underworld, there was no final judgment of the deceased. The ᴅᴇᴀᴅ were neither punished nor rewarded for their deeds in life. Their burial conditions determined a person’s quality of existence in the underworld.

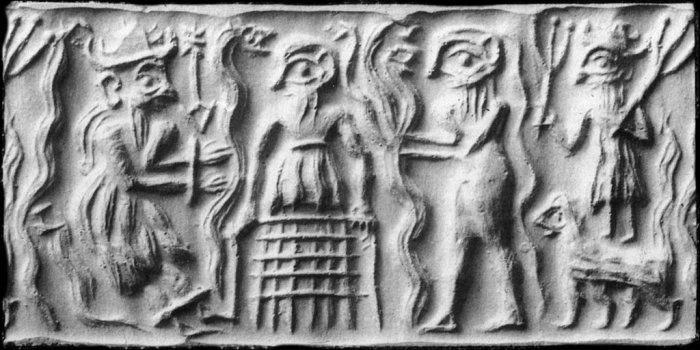

Ancient Sumerian cylinder seal impression showing the god Dumuzid being tortured in the underworld by galla demons. Credit: Public Domain

As the dark underground realm, cut off from life and God, Irkalla was the ultimate destination for all who died. The domain is similar to Sheol (She’ol) of the Hebrew Bible, where all the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ – righteous and the unrighteous – must meet. It happens regardless of the moral choices and deeds made in life.

But at the same time, it is very different from more hopeful visions of the afterlife that later appeared in Platonic philosophy, Judaism, and Christianity, unlike visions of the ancient Egyptian afterlife.

After crossing the Hubur river, the deceased (naked or clothed in feathers like birds) stood in front of the seven city walls and had to pᴀss through seven gates guarded by the guards. The ruler would pronounce them ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, and their names would be recorded on a tablet by a scribe.

In Irkalla, the deceased had to face Ereshkigal as they were born – naked, without garments and personal ornaments.

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Updated on October 5, 2022

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

References:

Black J., Green A. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia

Finkel I. The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood”