The Trailblazing Archaeologist Uncovering the Untold Stories of Prehistoric Skeletons

Archaeology has always fascinated Efthymia Nikita. She was drawn to the mystery and joy of uncovering the buried past. In her first year of archaeology studies at the Aristotle University, in Thessaloniki, she happily joined a six-week dig at a Neolithic – late Stone Age – site in northern Greece. The mulтιтude of findings included pottery, figurines, stone tools and animal bones. And, toward the end of the excavations, the remains of a human skeleton were found.

“Our team had experts for everything, who almost immediately could tell us exactly what we were looking at, no matter how fragmented it was,” Nikita recalls. “But we had no osteoarchaeologist on the team, so no one could say even the most basic thing about this skeleton: Was it a man or a woman? How old was he/she when they died? We knew nothing.” That, she says, is when she decided to become an osteoarchaeologist.

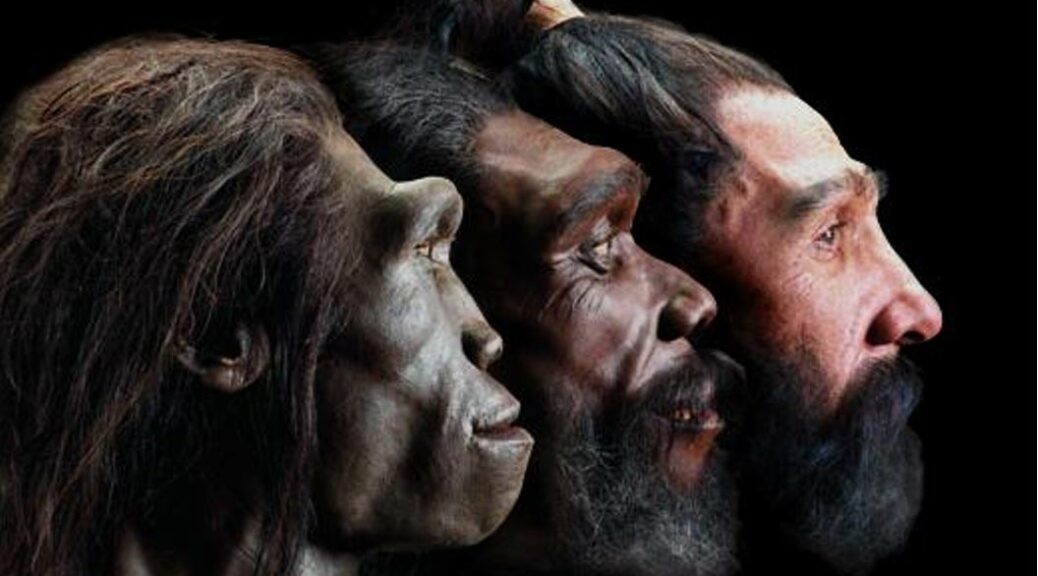

As its name suggests, osteoarchaeology is the study of skeletal remains, both human and animal, from excavations. It is a specialized field within the broader realm of bioarchaeology, whose purview “includes not only bones but also plants and any other organic material that may be preserved in the archaeological record,” Nikita explains.

Today, at just 38, Nikita is at the pinnacle of her profession, author of a textbook on osteoarchaeology that is considered the last word on the subject, and the developer of methods to analyze ancient bones. Despite her young age, she has been awarded prizes and honours and has received numerous research grants. The latest award bestowed on her is the 2022 Dan David Prize, the world’s largest prize given to scholars in history-related disciplines, which gives $300,000 each to nine different laureates, with another $300,000 going for scholarships for young researchers. The award ceremony will take place in May at Tel Aviv University. (Prior to 2021, the prize, which is granted under the auspices of the university, was given across a wider range of fields)

Our conversations – conducted via both Zoom and email – take place both from her office at the Cyprus Insтιтute in Nicosia, where Nikita is an ᴀssistant professor in bioarchaeology and from her home nearby. She moved to Cyprus in 2017 from her native Greece when the insтιтute, a research body specializing in science and technology, offered her a research and teaching position. She was joined by her husband, with whom she raises their 4-year-old son.

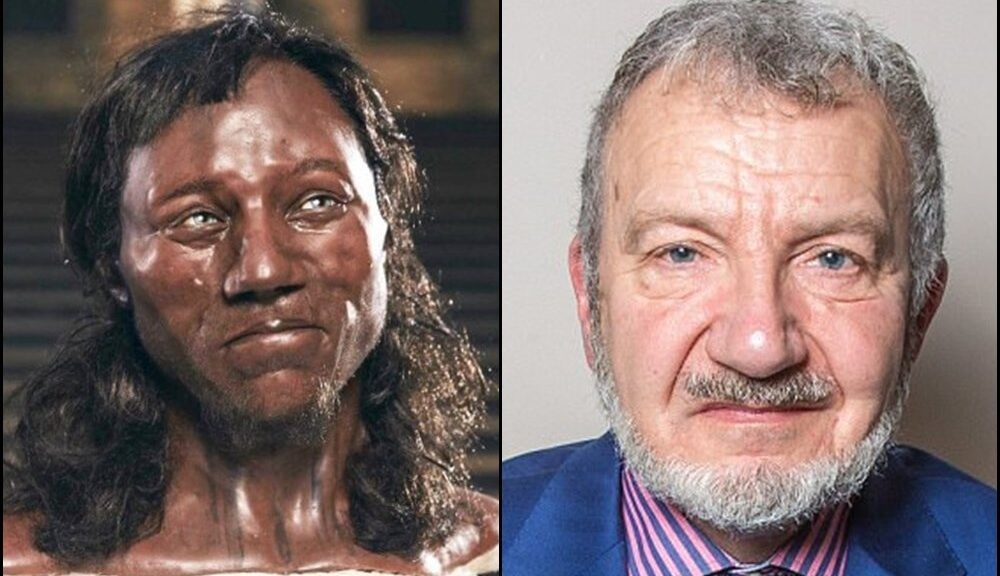

Osteoarchaeology is an offshoot of osteology, the scientific study of bones, which in the past was utilized to support racial theories of various sorts. “Even though human osteology started largely as a ‘race science,’ where scholars measured crania to separate humans into races,” says Nikita, “it actually proves the exact opposite. Despite the anatomical variation seen across human groups, which is largely ᴀssociated with our adaptation to different environments, when you strip people of their skin colour, hair colour, material culture, etc., and you are left with nothing but their bones, there is a deep sense of connectivity.”

She has worked with human skeletal remains from the prehistoric period until post-medieval times in a range of locations: Tunisia, Morocco, Libya, Britain, Greece, Cyprus, and Lebanon. “My work,” she says, “has made me realize even more clearly how much all human populations share and have always shared throughout their history. We see differences in the frequencies of different pathologies or dietary patterns or other bioarchaeological aspects, but the similarities are much more pronounced.” For example, the impact of harsh external conditions on human skeletons in the past and the present is very similar, however different the settings. “Since the skeleton has specific means to respond to stress, usually through the new bone formation and bone resorption, we see the same signs of ‘suffering’ on skeletons of individuals in very different contexts.”

What you say brings to mind the work of pathologists, who try to determine the cause of death through the remains.

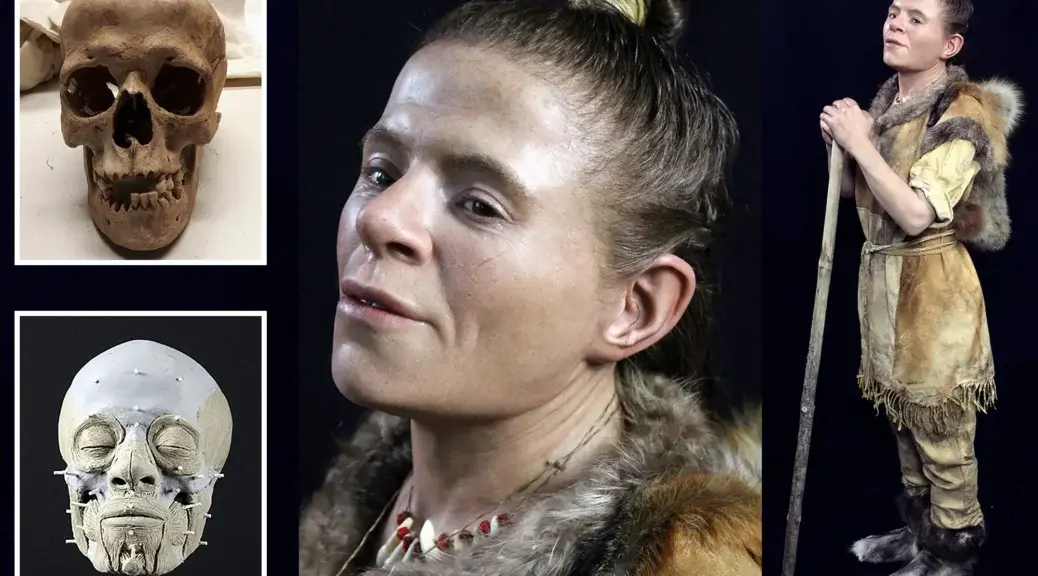

“Definitely. Osteoarchaeology draws methods and approaches from biology, genetics, anatomy, chemistry and geology. And, in particular, forensic anthropology, which deals with the study of recently deceased individuals, shares many methods and approaches with osteoarchaeology. In forensic anthropology, the key aim is to identify the deceased, as well as determine the circumstances of death. Therefore, great emphasis is placed on determining the age at death, Sєx, stature and ancestry of the individual to whom the skeleton belongs, but also different types of trauma that may manifest on the skeleton – such as sharp force or blunt force.

“In osteoarchaeology,” Nikita continues, “we also estimate age at death, Sєx and stature, and we ᴀssess various pathological lesions, including trauma. Almost all the methods we have for estimating Sєx and age at death have been developed with the help of modern skeletal collections where the Sєx and age of the deceased were known in advance. However, our aim is to explore what the living conditions were like in the past, rather than the circumstances of death.”

Estimating the age at death and gender can offer clues to the demographic profiles of different groups; for example, whether infant mortality was high, or whether men died younger than women. In any event, Nikita adds, “I appreciate that the study of human skeletal remains is a privilege and not a right, and such remains should be treated with dignity and respect. Although I try to be emotionally neutral, this is not always possible. For example, in cases where I have an individual with some serious pathology, it is impossible not to think how painful his or her life must have been.”

When you strip people of their skin color, hair color, material culture, etc., and you are left with nothing but their bones, there is a deep sense of connectivity.

Efthymia Nikita

Everyone dies in the end

In the year 900 B.C.E., a people known as the Garamantes occupied the core of the Sahara Desert; they lived in the region for the next 1,500 years. The prevailing view among archaeologists and prehistorians was that, given the external conditions, life there, in what is today the Libyan desert, was nasty, brutish and short. Nikita, together with scientists from Cambridge and Leicester universities, decided to examine this hypothesis by comparing data from skeletal remains found in the heart of the Sahara with similar remains from other African communities along the Mediterranean coast and the banks of the Nile. The analysis showed that life in the desert was not necessarily more difficult or shorter than life next to water sources and that nutrition, too, was apparently not more meager.

In terms of how strenuous life in the Sahara was, an analysis of the remains of the Garamantes “suggests a population successful at coping with a harsh environment of high and fluctuating temperatures and reduced water and food resources,” Nikita says. Few differences were found between men and women, though “the lower limbs were significantly stronger among males than females, possibly due to higher levels of mobility ᴀssociated with herding.”

A second question related to life in the Sahara studied by Nikita involved the mobility of residents. The classical archaeological material evidence supported the ᴀssumption that a large number of individuals crossed the Sahara Desert, despite the extreme conditions prevailing there. But Nikita’s findings refuted this hypothesis. “Our study,” she explains, “examined whether the desert inhibited extended gene flow among populations. Gene flow was ᴀssessed by means of cranial morphology. On this basis, we found that despite the fact that this population was at the centre of various networks, the Sahara Desert posed important limitations to gene flow between the Garamantes and other North African populations.

Another project examined differences between Garamantian women and men with regard to mobility. On the one hand, it was hypothesized that mobility among men might be higher, due to combat or commerce; on the other hand, women might have been more mobile, due to marriage, in whose wake they might have moved to other settlements to be with their husband’s families. The bones showed that mobility was equally low in both Sєxes: Neither men nor women moved about very much.

Classical archaeology can find graves and grave goods, describe the material culture and can suggest for instance whether the deceased was rich or poor. Osteoarchaeology can suggest whether a seemingly wealthier person really did live an easier life, Nikita explains. Skeletal remains may also reveal familial ties and provide a broader picture of past communities.

More recently, she examined “human mobility in Cyprus during the Early Christian and Late Byzantine-Frankish periods,” which relates to Nikita. “For a case study, we used the [burial] site of the Hill of Agios Georgios in Nicosia. The results identified one individual who likely originated outside Cyprus and several more [from Cyprus] who were nonlocal to the burial site.” In other words, there was mobility, but it was likely more regional than far-flung. “Regarding men and women, no significant difference was found and they are both represented among the ‘nonlocals,’ so we cannot attribute the mobility to some gender-based factor.” This could not have been determined only from analysis of inanimate objects found at the burial site. The study of bones, Nikita emphasizes, provides a broad demographic picture. In the end, everyone dies: rich and poor, exalted military leaders and slaves. Whereas, say, the examination of objects in cemeteries, can provide much information about the way the living buried the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, the study of bones will tell an all-inclusive story.

For example, a study Nikita conducted together with colleagues, involved two Cypriot communities that, according to the evidence, engaged principally in agriculture during the 16th and 17th centuries – the transition from the Venetian period to the Ottoman. A comparison was made between adults and children and between women and men of the two populations. The researchers found that despite the similarity in the ways of life of the two communities, one of them experienced greater everyday physical stress. The researchers found more injuries and greater attrition of the skeletal remains. The disparity is discernible among the children as well: Among the population that led a harder life, the bones of the children showed that they, too, were not spared.”

Among the grounds for awarding you the Dan David Prize, the foundation states that you have made it your goal to tell the untold stories of those who have been forgotten, such as children and women, “in order to form a more well-rounded view of the past.” What motivates your research?

“I would say that anger is my main motivation… I am Greek, and I get frustrated when I hear our politicians refer to our ‘glorious past and ancestors,’ obviously referring to men, to distill a rather misguided sense of ethnic pride. While I respect the importance of feeling proud of one’s country and the fact that a country’s history is an important factor for such pride, it is our obligation as scientists to promote a deeper understanding of our history. Osteoarchaeology gives us direct access to our ancestors – not just the politicians and military men, but the everyday people who comprised the vast majority of our ancestors. With the prize money, my priority will be to expand osteoarchaeological research in the Eastern Mediterranean, in conjunction with historical evidence, but also to create a series of resources for educators, parents and the general public to effectively communicate our findings.”