Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Archaeologists have been researching an area under the North Sea known as Doggerland, which was home to one of the largest prehistoric settlements in Europe.

But with the expansion of wind farms in the North Sea, the race is on to work with developers to piece together information about Doggerland in advance of development. Scientists now say magnetic fields could provide the key to understanding submerged civilizations.

Dogger Bank (located underneath the red outline) exists today and was once surrounded by Doggerland. Credit: Public Domain

A pioneering study by the University of Bradford may shed new light on prehistoric underwater sites and provide new information about our past.

Ph.D. student Ben Urmston will look for anomalies in magnetic fields by analysing magnetometry data, which could indicate the presence of archaeological features without excavation.

He said: “Small changes in the magnetic field can indicate changes in the landscape, such as peat-forming areas and sediments, or where erosion has occurred, for example in river channels.

“As the area we are studying used to be above sea level, there’s a small chance this analysis could even reveal evidence for hunter-gatherer activity. That would be the pinnacle.

“We might also discover the presence of middens, which are rubbish dumps that consist of animal bone, mollusc shells and other biological material, that can tell us a lot about how people lived.”

Doggerland

Doggerland was amongst the most resource-rich and ecologically dynamic areas during the later Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods (c.20,000 – 4,000 BC), lost to the sea by global warming at the end of the last ice age.

No in situ remains have been found and the only artefacts from the 185,000km2 site were recovered largely by chance, meaning our knowledge of the inhabitants and their lifestyles is extremely limited.

In a press statement, Ben added: “If we detect features that could indicate a midden, for example, we can then target that area and take a sample of the seabed. We can send the organic matter for carbon dating, which can usually tell within a decade or two when that was laid down.

“We are hoping the data we have been given will match up with areas already studied by the Lost Frontiers team at the University, to add to knowledge built over the last 20 years. It’s feeding into an active area of interest and research.”

The University of Bradford’s School of Archaeological and Forensic Sciences, which was awarded the prestigious Queen’s Anniversary Prize in November 2021, is well known as a global hub of digital heritage and marine palaeolandscape research.

Its Submerged Landscape Research Group has previously explored Doggerland through a combination of seismic mapping, the study of sediments and current knowledge of prehistoric behaviour.

Scholarship

Magnetometry has previously been used by terrestrial archaeologists but has not been used extensively to examine submerged landscapes.

It is a first for the University, made possible through a donation of £50,000 from The David and Claudia Harding Foundation to fund The Harding PhD Scholar in Marine Palaeolandscapes.

The Foundation’s Executive Director James Holmes said, “We are excited to be able to support research into one of the more intriguing chapters of European history and anticipate that a systematic, data-driven approach to marine archaeology will unveil many mysteries in the coming years.”

The University has provided match funding to create the fully funded Ph.D. studentship.

Magnetic fields data sets have been generously provided by engineering consultancy firm Royal Haskoning, which has been surveying the North Sea as part of an environmental impact ᴀssessment.

Professor Vince Gaffney, academic lead for the project, said: “Exploring the submerged landscapes beneath the North Sea represents one of the last great challenges to archaeology. Achieving this is becoming even more urgent with the rapid development of the North Sea for renewable energy.

“Bradford’s Submerged Landscape Research Group is at the forefront of such studies but this generous gift from Sir David Harding will ᴀssist significantly in this mᴀssive undertaking.”

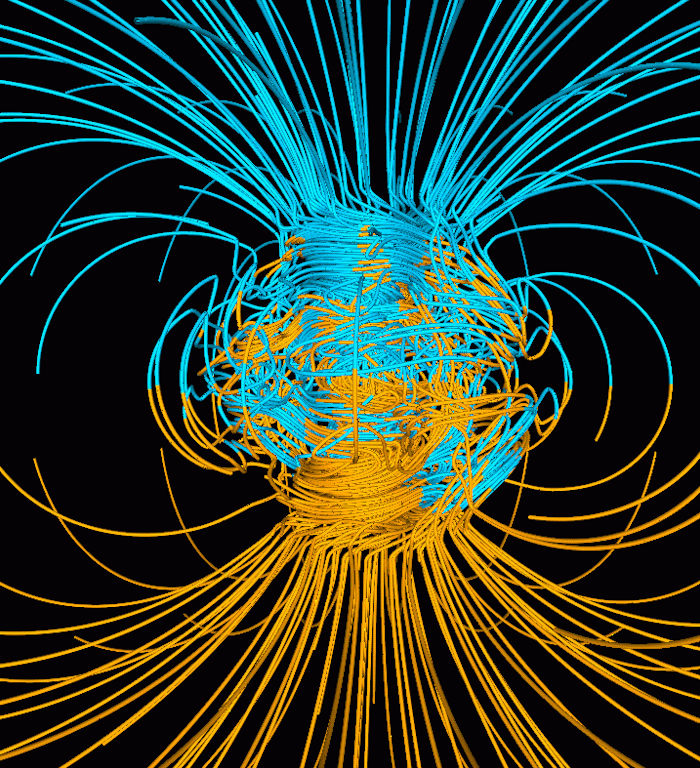

Computer simulation of Earth’s field in a period of normal polarity between reversals.[1] The lines represent magnetic field lines, blue when the field points towards the center and yellow when away. The rotation axis of Earth is centered and vertical. The dense clusters of lines are within Earth’s core. Credit: Public Domain

Ben, who has an MA in Archaeological Geophysics from the University of Bradford and has 20 years’ experience working as a geophysicist, said: “This funding will allow the archaeological ᴀssessment of high resolution magnetometer data collected as part of the construction process of current and future offshore renewable energy ᴀssets, providing an exciting and unique opportunity to contribute to both cultural heritage protection and environmental sustainability outcomes.

“I would like to express my sincere thanks to the Trustees of the David and Claudia Harding Foundation for their generosity in making this research possible.”

How is magnetic data collected?

Magnetic data is collected by companies looking to extract oil, gas and minerals from the seabed, and increasingly by offshore wind farming companies, to understand the landscape ahead of construction.

Exploration mainly looks for shipwrecks and unexploded wartime weapons and bombs.

Magnetometers are instruments which look similar to torpedoes, which are dragged through the water by cables attached to survey vessels to survey the magnetic fields on the seabed.

Race against time

Prehistoric archaeology within submerged coastal landscapes is facing considerable risk.

There is an unprecedented expansion of offshore wind power to combat climate change, spearheaded by the UK’s commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050.

See also: more Archaeology News

Offshore developments may eventually result in parts of the seascape becoming increasingly inaccessible. By working with developers, such as Royal Haskoning, scientists are able to use the opportunity to explore the seabed for prehistoric activity.

The University of Bradford is determined to respond positively to the development of clean energy while urgently addressing the risk to global marine palaeolandscapes.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer