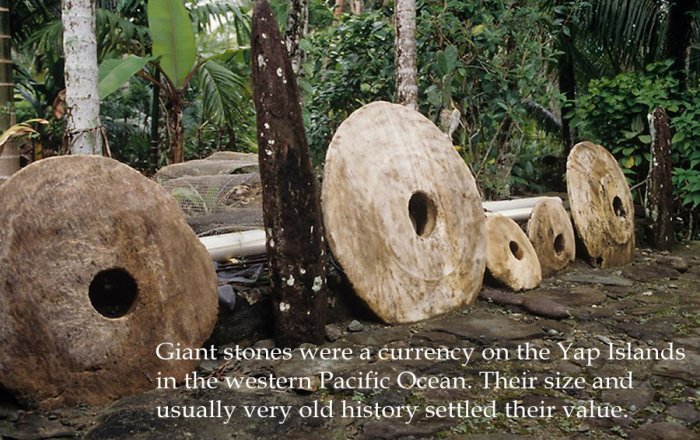

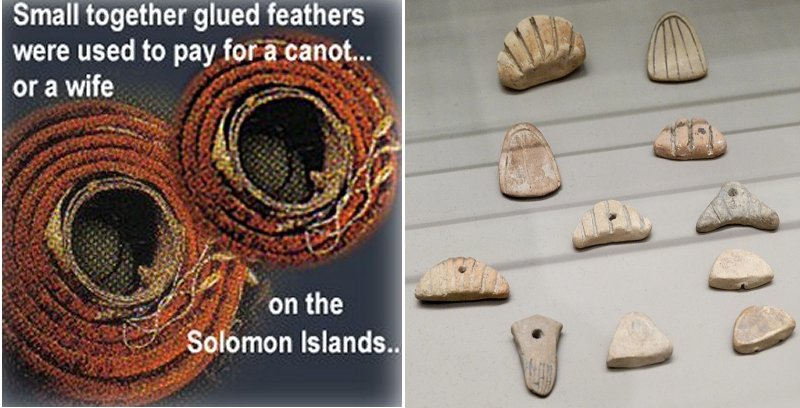

A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – Money has been available in all shapes and weight classes. They could be light as a feather or heavy like a stone. Small, together glued feathers were used to pay for a wife or canoe on the Solomon Islands, and giant stones were a currency on the Yap Islands in the western Pacific Ocean.

The stone’s size and age usually settled their value. The more stone-like disks a person or a family possessed, the higher the owner’s status among the locals.

In some of the world’s most exotic places, even salt was considered an authentic currency, and in many places around the world, it was even more precious than gold. Salt was cherished as a healer, preserver, and important symbol of life and blood. It has been considered a token of love and a guard against evil.

Before the notes and coins appeared in Ethiopia, the famous salt bar periodically had a higher value than gold. It was the most widely accepted currency and circulated as money in Ethiopia.

Two bars of salt could be exchanged for about 16 kilos of wheat. Indians of eastern North America used the belts of shells as money between white men and Indians.

The pattern determined the value of the belt. Rings of metal were used in West Africa until 1948. The precious rings were often used to pay for enslaved people.

During the 13th century, the Jews were driven from most of Europe, and the last Templars were executed or imprisoned. Money has been available in all shapes and weight classes. These two groups had long had a monopoly on the existing banking, and when they disappeared, it became impossible to change or borrow money.

Wealthy Italian families immediately saw their chance and established Europe’s first banks. From their tables (in Italian, “Banco”), they provided all creditworthy people with money at the marketplaces, and soon the Italiens had a monopoly over all banking in Europe. They had branches in most countries and earned wealth.

However, unlike contemporary banks giving loans, the Italians could not do it formally according to the Holy Bible. Throughout Christendom, lending money and charging the borrower interest or simply usury was prohibited.

The Church considered it a terrible sin, and the civil powers upheld the code. There were harsh penalties for those who broke the law.

The Prophet Ezekiel includes usury in a list of “abominable things,” including rape, murder, robbery, and idolatry.

“If you lend money to one of my people among you who is needy, do not be like a moneylender; charge him no interest.” -Exodus 22:25

For some reason, bankers did not want to be excluded from the Church. Were they perhaps afraid to be treated like all usurers and placed “at the lowest ledge in the seventh circle of hell – lower than murderers,” as Dante wrote in his famous “The Inferno”? Their solution to the dilemma was to issue bills. The borrower “sold” the bill to the bank for a certain amount and “bought” it later for a higher amount. Thus, there was no loan – only the purchase and sale of a document.

Silver coin of the Maurya Empire, known as rūpyarūpa, with symbols of wheel and elephant. 3rd century BC. Image credit: Per Honor et Gloria – Public Domain

Money does not always bring luck! Especially, paper money left “so deep trauma that paper money did not see the light of day in the country again until after the 1790s…” (D.N. Chorafas, “Wealth management”)

John Law (1671-1729), a Scottish gambler, murderer, playboy, and brilliant mathematician, contributed to an economic bankruptcy in France in the early 17th century. Paper money was already in use in China much earlier, and now, it was time to introduce them in Europe.

It took place in France in 1716 when John Law created France’s first public bank, known as the Banque Générale, a bank with the authority to issue notes. Law, responsible for the use of paper money today, believed that money was only a medium of exchange that did not consтιтute wealth in itself and that national wealth depended on trade.

He argued that metallic money is unreliable in quality and quanтιтy. Bank notes issued and managed by a public bank would remove the brakes on the economy.

Right: Uruk period counting stones from Susa in Mesopotamia. Money already served as a unit of account in early agrarian societies. Image credit: Marie-Lan Nguyen – Public domain

While in London, this highly controversial man studied finance, practiced gallantry, and managed to gamble away a fortune. He became an expert gambler, using his mathematical and statistical genius to win card games by mentally calculating the odds.

He had managed to convince King Philip II of France that the country’s large public debt could be solved by issuing banknotes with value guaranteed by the king.

John Law was, in fact, very persuasive. He became a director of the East India Company, which traded with the French colonies and began selling shares in the company. Only during some years, the company’s shares increased by 3.600 percent! The company grew and created a need for more Royal banknotes because John Law overestimated the colony’s ᴀssets.

And then, the great bubble burst! Both the Company and the Bank went bankrupt over one night; a severe financial crisis impacted France and Europe.

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Read part 1 of this article

Read part 2 of this article

Expand for references

References:

G. Davies, “History of Money”

S.R. Wagel, “Chinese Currency And Banking”