A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – Pi-Ramesse (Piramesse) is an example of an ancient city of great importance, which archaeologists surprisingly identified in two locations.

Reconstruction of the city of Pi-Ramesse in the early 13th-century BC, 2016. © artefacts-berlin.de.

It took a long time for them to piece together artifacts from these two sites and create an accurate image of Pi-Ramesse (also called Per Ramessu).

Seti I founded Pi-Ramesse, and his son Ramesses who reigned 1279–1213 BC, turned it into the influential metropolis of the Ramesside kings of the 13th – 12th centuries BC.

In the meantime, Thebes and Memphis functioned as religious and administrative centers.

Qantir, which is situated approximately 100 km from Cairo, Egypt, is the modern name of the site of Pi-Ramesses (“The city of Ramesses” or “(“House or Domain of Ramesses”), which was also an important harbor town.

Later, after Pharaoh Ramesses’s death, Pi-Ramesse was relocated from one place to another. The original location of the ancient city was widely debated. Among many theories, one identified Pi-Ramesses with Tanis, where archaeologists discovered many monuments.

They also found that many artifacts did not originate at the site of Tanis; they had to belong elsewhere.

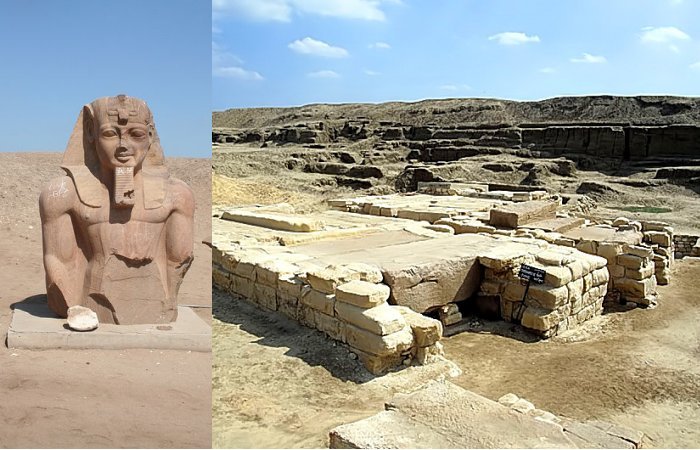

Left: Statue of Pharaoh Ramesses II at Tanis, Egypt. Credit: Einsamer Schütze – CC BY-SA 3.0 – Right: Tomb group at the Royal cemetery, view to the entrance of the tomb of Psusennes I, San el-Hagar (Tanis), Egypt. Credit: Roland Unger – CC BY-SA 3.0

Yet another theory was proposed by two Egyptian scholars who first connected the ancient Pi-Ramesse with Avaris, the capital of the Hyksos located only one kilometer south of Qantir. Their theory was confirmed fifty years later during excavations led by Austrian Egyptologist Manfred Bietak at the University of Vienna, Austria.

His works at two sites gave remarkable results; the modern town of Tell el-Dab’a was identified as Avaris, the capital of Egypt from 1650–to 1580 BC.

It was also established that the original site of Pi-Ramesse lay beneath the present-day city of Qantir, probably the ancient site of the 19th Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II’s capital, Pi-Ramesses or Per-Ramesses (“House or Domain of Ramesses”). This city is about 9 kilometers (5.5 miles) north of Faqus in the Sharqiya province of the eastern Nile Delta (about 60 miles northeast of Cairo).

The 1929 archaeological excavations revealed the remains of a mud-brick palace that existed in the area during the earliest phase of the town. Fifty years later, further digs revealed pottery dated to the reign of Seti I and Ramesses II and military barrack-rooms multi-functional workshops also dated to the Ramesside period.

Red granite head of King Ramesses II. This head comes from a colossal statue of Ramesses II, who is shown wearing a god’s wig and beard. Hieroglyphs next to the king give one of his names and promise he will be ‘given life’. This statue was probably originally set up at the royal city built by Ramesses II in the Nile Delta, called Pi-Ramesses. Many of this city’s monuments were moved by later kings when the royal residence shifted to the nearby city of Bubastis. Bubastis, Reign of Ramesses II (c. 1279-1213 BC). Credit: Mike Peel – CC-BY-SA-4.0

Presence Of Hitтιтes and Mycenaeans In Pi-Ramesse Metropolis

Successful excavations in the area of the Pi-Ramesses revealed at least 30,000 square kilometers of the large area occupied by metalworking, including many tools and artifacts, giving the complete picture of the charioteers’ armory.

The recovered items include lance heads, pieces of scaled body armor belonging to helmets, lances, daggers, arrowheads, a functioning pair of horse bits, a nave cap made of bronze, and horse bits. Other finds include a complex of stables and chariot workshops with limestone molds for embossing metal sheets.

The findings confirmed the presence of Hitтιтe soldiers, workers, Mycenaeans, and their pottery in Pi-Ramesse.

Tile showing an aquatic scene from a palace of Rameses II at Qantir. from the palace of Ramesses II. Image credit: Public Domain

The discoveries support existing evidence of foreign relations of Ramesside Egypt, which have been known mainly from the cuneiform archives at Hattusa/Boghazkoy in Anatolia.

One tablet, currently on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, details the terms of a crucial peace settlement reached years after the Battle of Kadesh between the Hitтιтes and the Egyptians under Ramesses II in 1259 or 1258 BC.

‘Egyptians and Hitтιтes worked peacefully, side by side. It also holds for the motif on the back of the molds, depicting a highly stylized head of a bull, a symbol of the Hitтιтe weather god.

The most likely explanation for the peaceful presence of Hitтιтes in Egypt’s Ramessid capital is the occasion of the diplomatic marriage between Ramesses II and the eldest daughter of the Hitтιтe king Hattusili III, Maathorneferure, which took place in Year 34 of Ramesses II’s reign.

The ruins of Tanis today, Image credit: Markh – Public Domain

In several texts, particular emphasis is placed on the friendly encounter of the formerly hostile troops, enabling the ancient historians to state that “both lands had become one (and the same) land.” (The Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt)

‘The shield molds with the Hitтιтe motifs must have been used to maintain the shields of the Hitтιтes who served as a palace or bodyguard for the queen in the Ramessid residence. [These molds] represent an outward expression of the friendly union between the two superpowers.’

Pi-Ramesse flourished until 1078 BC. When the branch of the Nile slowly began to dry up, it was time to move the city with all its temples, statues, and obelisks to the newly founded city of Tanis.

The new site remained important until it was finally abandoned in the sixth century AD.

Today only small parts of ancient Pi-Ramesse can be explored. Most of the area is privately owned, and excavations cannot be authorized; essential knowledge about the city’s ordinary life remains buried under the surface.

Written by – A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Updated on April 10, 2023

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

References:

Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt

H. Wilkinson, The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt

A. Dearman, M. P. Graham, Essays on the History and Archaeology of the Ancient Near East

Weaver, Ancient Egypt

Monroe Edgar – Qantir, Ancient Pi-Ramesse