Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – A new extinct reptile species has shed light on how our earliest ancestors became top predators by modifying their teeth in response to environmental instability around 300 million years ago.

In findings published in Royal Society Open Science, researchers at the University of Bristol have discovered that this evolutionary adaptation laid the foundations for the incisor, canine and molar teeth that all mammals — including humans — possess today.

Le Moustier Neanderthals (Charles R. Knight, 1920). Credit: Public Domain

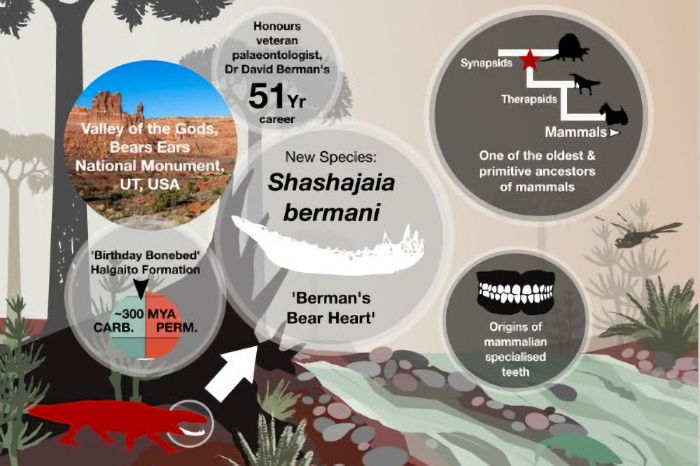

Shashajaia is one of the most primitive members of a group called the Sphenacodontoidea, which includes the famous sail-backed Dimetrodon, and mammal-like reptiles known as therapsids, which eventually evolved into mammals. It is remarkable for its age and anatomy, possessing a very unique set of teeth that set it apart from other synapsids — meaning the animal lineage that mammals belong to — of the time.

Dr Suresh Singh of the School of Earth Sciences explained: “The teeth show clear differentiation in shape between the front and back of the jaw, organised into distinct regions. This is the basic precursor of what mammals have today — incisors and canines up front, with molars in the back. This is the oldest record of such teeth in our evolutionary tree.”

The novel denтιтion of Shashajaia demonstratesthat large, canine-like differentiated teeth were present in synapsids by the Late Carboniferous period — a time famous for giant insects and the global swampy rainforests that produced much of our coal deposits.

Shashajaia jaw. Credit: Dr Adam Huttenlocker

By analytically comparing the tooth variation observed in Shashajaia with other synapsids, the study suggests that distinctive, specialised teeth likely emerged in our synapsid ancestors as a predatory adaptation to help them catch prey at a time when global climate change approximately 300 million years ago saw once-prevalent Carboniferous wetlands replaced by more arid, seasonal environments. These new, more changeable conditions brought a change in the availability and diversity of prey.

Lead author Dr Adam Huttenlocker of the University of Southern California said: “Canine-like teeth in small sphenacodonts like Shashajaia might have facilitated a fast, raptorial bite in riparian habitats where a mix of terrestrial and semi-aquatic prey could be found in abundance.”

Infographic showing differentiated teeth. Credit: Dr Suresh Singh

The new reptile is one of the oldest synapsids. It was named “Shashajaia bermani,” which translates as Berman’s bear heart, to honour the 51-year career of veteran palaeontologist, Dr David Berman of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, as well as the local Navajo people of the discovery site within the Bears Ears National Monument, Utah.

Dr Singh said: “The study is a testament to Dr Berman who originally discovered the fossil site in 1989, and his decades of work on synapsids and other early tetrapods from the Bears Ears region of Utah which helped to justify the Bears Ears National Monument in 2016.”

See also: More Archaeology News

The site is located within an area known as the Valley of the Gods and is of huge importance to palaeontologists.

“The Monument archives the final stages of the Late Paleozoic Ice Ages, so understanding changes in its fossil ᴀssemblages through time will shed light on how climate change can drastically alter ecosystems in deep time, as well as in the present,” added Dr Huttenlocker.

paper

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer