Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com – A long time ago, a woman who lived in Thebes, Egypt, was mummified and placed inside a beautiful sarcophagus. The lady was a prominent member of Egyptian society.

Outstanding funerary objects were put inside the coffin to accompany her on the journey to the afterlife. For 2,7000 years, her mummified body rested peacefully inside the sarcophagus until the ancient Egyptian coffin was destroyed in Brazil.

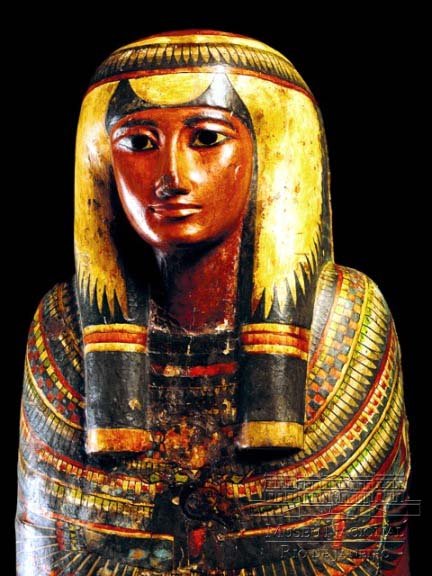

Priestly singer Sha-Amun-en-su. Credit: – Public Domain

The loss of Sha-Amun-en-su’s sarcophagus is unfortunate because the ancient coffin was rare.

Mystery Surrounds Sha-Amun-en-su And Her Sarcophagus

Sha-Amun-en-su was an ancient Egyptian singer and priestess who lived during the twenty-second Dynasty of Egypt, founded by Pharaoh Shishak (Sheshonq I). Unfortunately, there is virtually no information about Sha-Amun-en-su except the hieroglyphic inscriptions on her casket. Fortunately, scientists could study the coffin and conduct some analysis before everything was lost to history.

Sha-Amun-en-su will forever remain a woman shrouded in mystery.

It is unknown when, where, and who unearthed her sarcophagus. The ancient singer’s coffin was found near the Thebes complex, but the precise location remains undetermined. There is also no information about Sha-Amun-en-su’s biological family, but one inscription reveals she had an adopted daughter.

What is known is that Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II (1825 – 1891) visited Egypt in 1875 and was offered the sarcophagus as a gift by Ismail Pasha. Being very interested in ancient Egyptian history and culture, Dom Pedro II took the coffin to the Palace of São Cristóvão, where it stood until the Proclamation of the Republic in 1889.

Why The Sarcophagus Of Sha-Amun-en-su Was Destroyed

The first damage to the coffin of Sha-Amun-en-su occurred while it was still in possession of Dom Pedro II. One day, during a storm, the ancient Egyptian sarcophagus was knocked down by the wind. The coffin fell and crashed into Dom Pedro II’s office window.

When the sarcophagus was moved from Dom Pedro’s palace to the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro, it could be admired and studied for many years. Unfortunately, on September 2, 2018, a major fire destroyed the National Museum. The fire consumed Sha-Amun-en-su’s sarcophagus, mummy, and all her votive artifacts. It was possible to repair the coffin, but the damage on its left side was visible.

Sarcophagus of Sha-Amun-en-su before it was destroyed in 2018. Credit: Dornicke – CC BY-SA 4.0

To historians, archaeologists, and people interested in ancient Egyptian history, it was a sad and depressing day.

Sha-Amun-en-su’s Life As One Of The Heset Members

Before her coffin was lost, scientists had a couple of years to study the hieroglyphics on the coffin. Academics learned that Sha-Amun-en-su was a member of the Heset, which means “singer.” A hieroglyphic inscription on her casket stated she was “daughter of Sha-Amun-en-su, singer of the shrine of Amun.”

The Heset members were female priestly singers at Amun’s shrine who ritual for Gods and Goddesses.” In ancient Egypt, where religion was an essential part of daily life, everything focused on pleasing the gods.

Egyptian priests devoted their lives to the gods and goddesses.

It was believed that the human world was rather dirty, so priests and priestesses had to take care of the temple and the statue of the god.

“Each statue was cleaned daily with lotus-scented water, anointed with oil, dressed, and decorated with jewelry and make-up. Also, priests themselves would be extremely clean throughout the body.

Priests of both Sєxes usually spent several hours practicing the songs and dances to please the gods.” 1

Sha-Amun-en-su had many duties as a priestly singer. During ceremonies and festivals, she exercised ritualistic functions and sang hymns in honor of the god Amun.

Music and dance have always been important in Egypt. Ancient Egyptians also believed music could help people on their journey to the afterlife. Therefore, a combination of music and dance was necessary while performing rituals celebrating the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ.

Profile face detail on the sarcophagus of Sha-Amun-in-su. Credit: Gian Cornachini – CC BY-SA 4.0

In the case of Sha-Amun-en-su, her songs were essential in daily rituals when the deity had to wake up in the morning and go to sleep in the evening.

Since Sha-Amun-en-su’s sarcophus was never opened scientists could only relate what they discovered using x-ray technology. Experts determined she was about 50 years when she died, but the cause of her death remains unknown. However, her body appeared in good condition, with no traumas or injuries, suggesting she died of natural causes. She has teeth in excellent condition. Her throat was covered with resin-coated bandages to protect her vital organ, ensuring she could continue singing religious hymns in her next life.

Among her funerary artifacts was a beautiful heart scarab made of green stone engraved with her name. Her ancient coffin had been decorated with beautiful paintings of the God Osiris, the important Ankh symbol, the Four Sons of Horus, and many other significant afterlife symbols.

Sadly, anything related to Sha-Amun-en-su has been lost, and the woman’s life will forever remain an ancient mystery.

There is no way to retrieve the 2,700year-old sarcophagus of Sha-Amun-en-su, but we can at least preserve the memory of this ancient woman whose mummy left her home country and traveled to a different part of the world only to be destroyed in a fire.

Written by Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Updated on January 6, 2023

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

- Sutherland – Daily Life Of Priests And Priestesses In Ancient Egypt, AncientPages.com

- Emily Teeter – Female Musicians in Pharaonic Egypt – Rediscovering the Muses in Women’s Musical Traditions

- Wikipedia

- Scott, Nora. “The Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 31, no. 3 (1973): 123-70.