AncientPages.com – Spartacus, a lowly barbarian slave whose rebellion ultimately proved a failure and whose followers died in the most ignominious of fashions, has become a modern symbol of the power of freedom and the dignity of humanity.

The contemporary popularity of Spartacus must be especially galling to the many Roman heroes of the Republic. These men paid a great price to defend the state at various times. Yet nobody remembers their names. The consul Lucius Junius Brutus was such a patriot that he sentenced his own sons to death when he discovered that they were guilty of treason. The Horatii brothers swore an oath to defend Rome as her champions. Only one came back alive.

Spartacus: War of the Damned. Credit: Rotten Tomatoes

Gaius Mucius stuck his right hand into a blazing fire in order to demonstrate to the invading Etruscans just how brave and stoic the Romans were. It worked. The Etruscans sued for peace and Mucius was known for the rest of his life as “Lefty”. Yet today, these figures are almost entirely forgotten.

Talk about a figure standing alone on a bridge yelling, “You shall not pᴀss”, and everybody thinks of Gandalf from Lord of the Rings, not Horatius Cocles who single-handedly defended the bridge across the Tiber from overwhelming forces keen to sack Rome.

Roman history is not lacking in acts of bravery or self-sacrifice. What makes the Spartacus story different is the status of the protagonist.

We know little about the precise background of Spartacus. Our sources have him coming from Thrace, roughly modern Bulgaria. One ancient text claims he had once fought in the Roman army before being imprisoned. All agree he had been reduced to slavery and had been condemned to fight as a gladiator.

Spartacus the rebel

These days we tend to over-glamourize the status of gladiators. To the Romans, gladiators were the lowest of the low. You might admire their skill with a sword, but you were never in any doubt about their depravity and lack of moral fibre. They were no match for a proper Roman citizen.

It was this over-confident belief in their natural superiority that would prove the downfall of many of the Roman commanders sent against Spartacus. When Spartacus and 70 or so of his comrades revolted and escaped from their gladiatorial school near Capua in 73 BC, everyone imagined the matter would soon be dealt with.

They underestimated the skill of their opponent. Spartacus would turn out to be a master of the art of the surprise attack. He tied vines together to make ropes and climbed down cliffs to launch attacks on his enemies from behind. He waited until the Romans were bathing before springing a raid on their encampment.

This success was so unexpected that the Romans began to wonder if there wasn’t something supernatural about it. Quickly stories began to circulate about how Spartacus had been marked out by portents and signs of divine favour. In a sign of desperation, the Romans revived the punishment of decimation, killing one in ten of the most cowardly troops, in order to show the others the price of failure.

Spartacus was also ᴀssisted by a tremendous influx of slaves and the rural poor who joined his rebellion. The figures are unreliable, but some put the size of his army of outcasts as high as 90,000 men.

Certainly, the damage they did was significant. For two years they ravaged the Italian countryside from North to South until finally the Roman general Marcus Licinius Crᴀssus was able to defeat Spartacus and his army in open combat in 71 BC. Spartacus’ body was never recovered. Six thousand prisoners were crucified. Their bodies lined the road from Capua to Rome.

Russian artist Fyodor Bronnikov’s depiction of slaves crucified during Spartacus’ rebellion, 1878. Credit: Wikimedia

It had been a cruel war with acts of barbarism on both sides. Spartacus routinely killed the Roman prisoners he captured. Despite his entreaties, Spartacus’ army raped women, mutilated bodies, tortured captives, and burnt people alive in their houses. According to a late source, one of his commanders even staged a gladiatorial show using captives as gladiators. Those who had once been spectators were now the spectacle.

Strange legacy

It was the twin aspects of popular revolt and his status as a slave which ensured Spartacus’ rebellion did not end up as just a footnote in the history books. In the 19th century, anti-slavery campaigners were quick to seize on this story and transform it into an epic tale of a noble slave fighting for freedom.

Romantic dramatisations of the Spartacus story such as Robert Montgomery Bird’s The Gladiator played to packed houses in the United States and helped to galvanise abolitionist sentiment.

The Spartacus story proved equally popular within communist circles who were attracted to the idea of his rebellion as precursor to their own popular working-class revolutions. Karl Marx was a fan. Rosa Luxemburg when she founded the German communist Party named it after Spartacus.

When the communist Howard Fast was imprisoned for contempt of Congress for refusing to answer questions put to him by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, he used his time in prison to write a novel about Spartacus and his revolution. The novel would later be transformed by Dalton Trumbo, himself a victim of anti-Red purges in Hollywood, into the script for the celebrated film Spartacus starring Kirk Douglas as the rebellious leader.

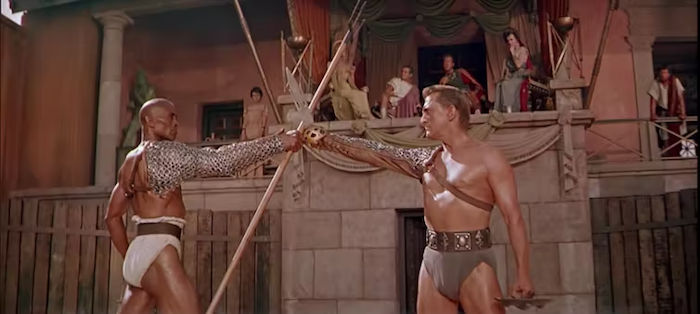

Kirk Douglas and Woody Strode in Spartacus (1960). Credit: IMDB

Given such communist credentials, it’s understandable Khachaturian’s ballet Spartacus became a popular work within Soviet Russia. The work won the Lenin prize for composition in 1954 and was a staple of the Bolshoi for many years.

Yet, the success of the ballet is not just the result of its ideological sympathies. It’s a ballet of powerful physicality. It makes tremendous demands of its male leads. Soldiers and gladiators clash. Slaves suffer. Violence and eroticism mingle. The ballet compels us to confront the very limits of muscle and sinew.

It exposes our humanity, our cruelty and nobility. It may take tremendous licence with historical events, but there is profound truth in its recognition that the appeal of Spartacus lies in the primal instinct of bodies to be free.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .![]()