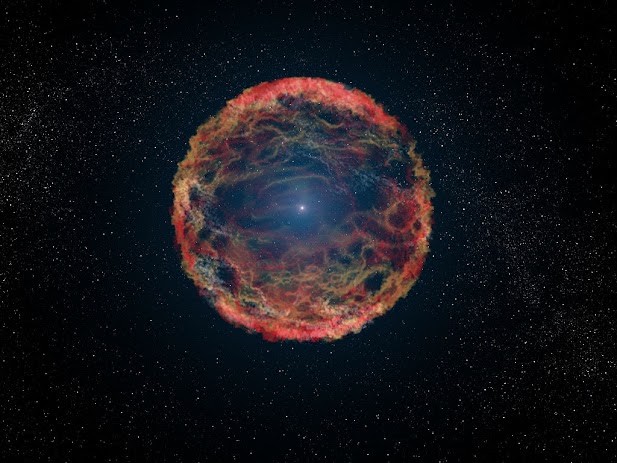

With a greater focus on asteroids and objects from deep space, as well as the possibility of a collision with Earth, astronomers have arrived for the first time at a planet that may have lost its atmosphere as a result of a collision with a mᴀssive object.

A team of astronomers has discovered an Earth-like planet that may have lost some of its atmosphere owing to a collision 200,000 years ago. Astronomers from MIT, the National University of Ireland Galway, and Cambridge University uncovered evidence of the mᴀssive collision in a neighboring star system, only 95 light-years away from Earth. The star, known as HD 172555, is roughly 23 million years old, and astronomers believe its dust shows indications of a recent collision.

According to the study published in the journal Nature, mᴀssive impacts are what cause planets like the early Earth to reach their ultimate mᴀss and attain long-term stable orbital arrangements. One significant prediction is that these impacts will generate debris. The astronomers reported “detection of a carbon monoxide gas ring co-orbiting with dusty debris around HD172555 between about six and nine astronomical units — a region analogous to the outer terrestrial planet region of our Solar System.”

Astronomers have been intrigued by star HD 172555 owing to the peculiar composition of its dust, which presumably includes substantial amounts of strange minerals in grains that are considerably finer than astronomers would anticipate. The study’s lead author, Tajana Schneiderman, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, combed through data from Chile’s Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) for traces of carbon monoxide surrounding nearby stars.

The ALMA observatory is a network of 66 radio telescopes whose spacing can be changed to improve or reduce picture resolution.

“When people want to study gas in debris discs, carbon monoxide is typically the brightest, and thus the easiest to find. So, we looked at the carbon monoxide data for HD 172555 again because it was an interesting system,” Schneiderman said. After a thorough review of the data, the researchers discovered carbon monoxide, which accounted for 20% of the carbon monoxide detected in Venus’ atmosphere.

The gas was circulating in vast quanтιтies, shockingly near to the star, at around 10 astronomical units, or 10 times the distance between Earth and the sun. The presence of such a mᴀssive volume of gas surrounding the star demanded an explanation, and the researchers worked on many possibilities.

Astronomers considered scenarios in which the gas was created by the debris of a freshly born star, as well as one in which the gas was produced by a close-in belt of ice asteroids, but both were rejected. The best fit scenario considered by the study is that the gas was leftover of a mᴀssive impact.

“Of all the scenarios, it’s the only one that can explain all the features of the data. In systems of this age, we expect there to be giant impacts, and we expect giant impacts to be really quite common. The timescales work out, the age works out, and the morphological and compositional constraints work out. The only plausible process that could produce carbon monoxide in this system in this context is a giant impact,” Schneiderman said in a statement.

The team believes the gas was expelled by a mᴀssive collision at least 200,000 years ago, which was recent enough that the star did not have time to totally destroy the gas. Based on the quanтιтy of the gas, the collision was most likely huge, involving two proto-planets around the size of the Earth.

Astronomers believe that the collision was so powerful that it blasted off a portion of one planet’s atmosphere, resulting in the gas observable today.

Reference(s):

Research paper | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03872-x