Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – They may not be often mentioned, but the Satraps played an essential role in ancient history. Satraps were governors of provinces of the Achaemenid Empire, and later its successors the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic Empire.

Satraps had similar responsibilities to the vizier, who next after the Pharaoh was the most influential person in ancient Egypt. As the highest state official, the vizier was the immediate subordinate of the king and responsible for legal matters, and thus feared by criminals. Satraps held a prestigious position as representatives of the king.

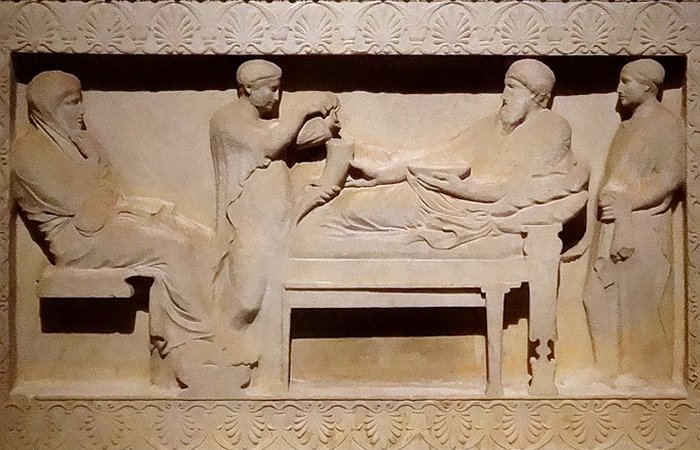

Satrap sarcophagus banquet scene. Credit: Javicu Curucho – CC BY-SA 2.0

Satraps were not only “responsible for delivering his messages but were also responsible for maintaining a level of order in whichever city they were stationed. They were essentially considered governors of the state. Satrap literally translates to “protector of the province,” meaning these individuals had a great responsibility bestowed to them. They would also collect taxes, control local officials, and acted as the supreme judge of the province for every criminal and civil case brought before them. Each Satrap had their own council of Persians to ᴀssist in their official affairs.” 1

The first Satraps emerged under Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire who conquered Medians, Lydians, and Babylonians.

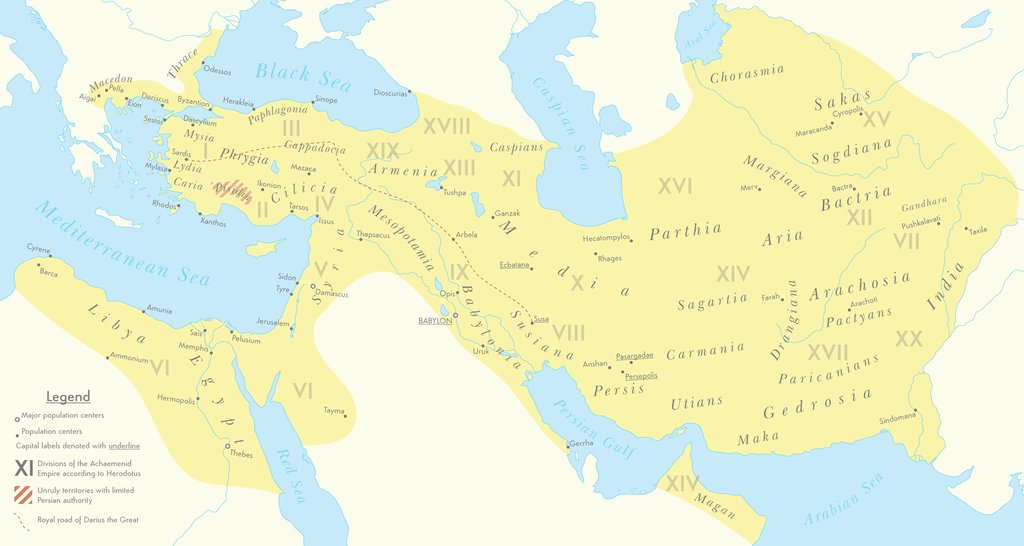

“The remaining eight years of his life Cyrus devoted, for the most part, to organising this great and heterogeneous empire he had acquired. He divided it into about twenty provinces, each under a viceroy whose Persian тιтle — khshathrapavan, ‘Protector of the Kingdom’ — was transliterated by the Greeks as satrapes, and has given us the generic term ‘satrap’. Two of these satrapies contained Greek subjects: Lydia, with its governmental seat at Sardis, included the Ionian seaboard, while Phrygia covered the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara [Propontis], and the southern shore of the Black Sea.

These satraps, especially in the vast eastern provinces, wielded enormous power. They not only concentrated all civil administration in their own hands, but acted as military commander-in-chief as well. Such centralisation of authority was convenient, but had obvious dangers — not least that some ambitious governor might become too big for his satrapal boots, and attempt to usurp the throne.

To avoid such a contingency, the Chief Secretary, senior Treasury official, and garrison commanders of each province were appointed by the Great King, and directly responsible to him.

More sinister was the travelling inspector, or commissar, known as ‘the Great King’s Eye’, who made a confidential yearly report on the state of every imperial province.” 2

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius I (522 BC to 486 BC) featuring ancient regions, settlements and Satrapies. Credit: Cattette – CC BY 4.0

The Satrapic administration continued to flourish long after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, and their influence reached far even to India. The Saka Satrpas of Western India were originally viceroys of the Kusanas of Kaniska’s house.

Having much power and eagerness to become even more influential, the Satraps could be dangerous to a leader of a kingdom and revolts were common. Artaxerxes III, also known as Ocho ruled Persia from 359 to

338, and had to put down a revolt of Satraps in Asia Minor. Later he and reconquered Egypt before he was ᴀssᴀssinated. One can also mention Artabazus, an important Persian leader who had been involved in a revolt by fellow Satraps against the king. Struggles for power and more land were common among the Satraps.

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references

- History, Captivating – Achaemenid Empire: A Captivating Guide to the First Persian Empire Founded by Cyrus the Great, and How This Empire of Ancient Persia Fought Against the Ancient Greeks in the Greco-Persian Wars

- Peter Green – The Greco-Persian Wars

- Sircar, D. (1966). Early Western Straps And The Date Of The Periplus. The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-), 6, 241-249.

- Pascual J. (2016). Conon, the Persian Fleet and a Second Naval Campaign in 393 BC. Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte,65(1), 14-30.

- Philip Freeman – Alexander the Great