Conny Waters – AncientPages.com -Researchers have shed new light on York’s medieval Jewish population, unearthing new documents and evidence which points to a thriving community where the chief Jewish citizens of the city were also some of the most important figures in England.

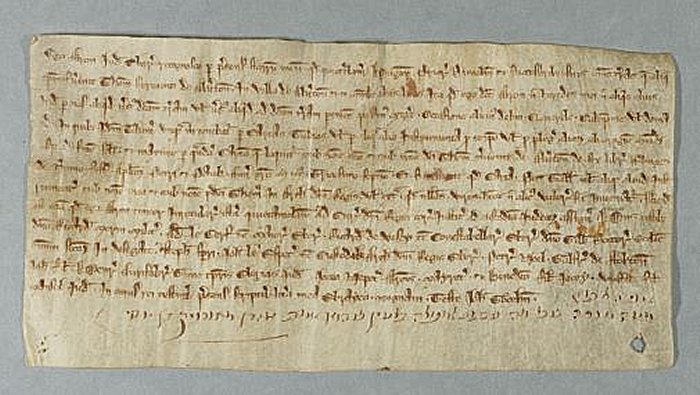

13th Century charter in Durham Cathedral Archives detailing Aaron of York’s financial dealings with the city. Pic credit: The Dean and Chapter of Durham”

The mᴀssacre of York’s Jews in 1190 has overshadowed the fact that from the 1210s onwards there was once more a thriving Jewish community living and working in the city in mostly harmonious relations with their Christian neighbours.

Digital reconstructions

Now a team from the University of York’s Heritage360 Streetlife project has undertaken new research on the “forgotten story of York’s medieval Jewish community.”

Based on new archival evidence, the team have created digital reconstructions of the houses where the chief Jewish citizens of York lived.

They have also identified the location of York’s first synagogue and how leading figures from the Jewish community cooperated with the senior clergy of York Minster in purchasing the large stone building which became the city’s Guildhall.

Key findings from the project include:

The three leading citizens of the post-1190 Jewish community lived on the west side of Coney Street, backing on to the river. The houses modelled by the project are those of Leo Episcopus (where Boots is now), his son-in-law Aaron of York (where Next is now), and Aaron’s nephew Josce le Jovene (Waterstones and Fabrication).

Leo and Aaron both served as chief representative of the whole Jewish community of England, and in the 1230s and 1240s Aaron was considered to be the richest man in the country.

The reconstructions of the houses are based on surviving medieval houses elsewhere in York, as well as comparable houses in Lincoln. They were originally built by Christian landlords and leased to the Jews, and would have been indistinguishable from the other houses on the street where the chief Christian citizens of York lived. Aaron’s house had a synagogue in its back plot, but this would not have been visible from the street.

The reconstructions show how the stone houses (called ‘solars’) had domestic quarters on the first floor but let out the ground floor as shops. Coney Street was an important commercial high street, and the range of shops depicted (including a clothier, leather worker, vintner, goldsmith, baker, and apothecary) is based on contemporary evidence for these trades operating in this area.

Charters from Durham Cathedral Archives show how Aaron of York cooperated with the senior clergy of York Minster in purchasing the large stone building which became the city’s Guildhall (the medieval civic centre), ensuring that the city had a central meeting-place and contributing greatly to York’s civic history.

It is also likely that Aaron co-operated with the Minster on other major civic projects, including the construction of the ‘Five Sisters’ window in the Minster itself (previously known as the ‘Jewish Window’), in return for land extending York’s Jewish cemetery.

The charter also provides a date, previously unknown, for when York acquired the Guildhall of 8th September 1231. Other charters from Durham have preserved Aaron’s own handwriting and signature, a rare survival at a time when charters were usually sealed, not signed.

New research has also pinpointed for the first time the exact locations of the houses of the two leading members of the pre-1190 Jewish community, Josce and Benedict, on Fossgate and Colliergate respectively. This also changes our understanding of where the city’s first synagogue would have been, and where the noted Rabbi Yom Tov would have taught, which was most likely on the south side of Fossgate.

Visual interpretation

“The digital reconstructions offer an accessible visual interpretation of how the Jewish community lived side-by-side with their Christian neighbours, including on York’s most high-status medieval street,” Dr Louise Hampson, project lead at the University of York, said in a press release.

Dr John Jenkins, researcher on the project, added: “The research brought to light the ways in which Jews and Christians worked together for the common good of the city, playing a key role in the acquisition of the civic Guildhall as well as in the rebuilding of York Minster, both of which remain important civic ᴀssets to this day.”

Howard Duckworth, Warden of the York Synagogue, said: “The amount of new information that has been uncovered by the team is truly inspiring and has now been recognised by Jews, not only in the UK, but across the world.

“We have discovered a totally new history of Jews in York, which for many years has been overshadowed by the mᴀssacre at Clifford’s Tower. This research is so much more, a real history anyone can relate to. When you walk through York now, you see York with totally different eyes, thanks to the team for all their work.”

An attendee of a recent workshop connected to the project said: “The research is very exciting, it’s really changed my understanding.

“The identification of the likely sites of the synagogues is so important and makes York a very important place when we are thinking about our scholars from the past”.

Further information:

The digital models are available to view on a touchscreen in the project’s ‘Streetlife Hub’ on 29-31 Coney Street, York, until February 2024, together with an exhibition on the street’s Jewish history.

A video of the models can also be seen as an installation in the window of Fabrication, 19 Coney Street.

Online information (https://streetlifeyork.uk/projects/jewish-coney-street) currently consists of an overview of the project and an interactive trail of Jewish York (https://streetlifeyork.uk/explore/trails/298).

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer